Centre County was, for the first half century or so of its history, cut off from more populated areas of Pennsylvania by the “Endless Mountains,” the long folded Appalachians that can be seen from nearly every point in the County.

Because this isolation limited exposure to new architectural ideas, early local building styles – folk housing – repeated styles that were similar to what had been built by the County’s first British and German settlers. As these styles changed over the years to meet an owner or builder’s own needs and ideas, they took on a vernacular style, meaning common or local.

While vernacular houses, plus conservative versions of earlier British styles continued to be built throughout the 1800s, new Victorian styles began to be introduced mid-century. Victorian fashion came to Centre County in architectural pattern books and popular journals, and through the arrival of railroads bringing news of other places and other ideas. By the 1860s, the county was being swept into the nation’s cultural mainstream. Architectural examples of a full range of Victorian styles – from Gothic Revival to Queen Anne – can be found throughout the County.

After the turn of the century, county residents had the opportunity to choose what best fitted their needs from a new set of increasingly available national styles. Craftsman Bungalows, Prairie-style Foursquares, Dutch and English Colonial Revivals, highly detailed English Tudor Revival homes, and even buildings in the International and Moderne styles were available through architect-designed plans, pattern books, and mail-order catalogs.

Early Housing

Log Houses

These first dwellings, constructed by early settlers to provide ready shelter until more substantial homes could replace them, were built with logs cut and shaped by hand. The gaps between the logs were filled or “chinked” with a mortar of lime, sand, clay, and horsehair, held in place by chunks of wood and crushed limestone. Most often the corners were notched and fitted together with a diamond or V-notch for structural security; window openings were usually small. Sometimes, as the family grew larger and became more prosperous, the log building was incorporated into a larger dwelling.

Plank Houses

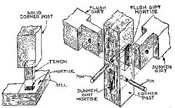

Vertical plank construction also was used for early houses. The planks were mortise and tenoned into heavy timbers used to form the outside frame, or in some cases, two overlapping layers of vertical planks were fitted into horizontal sills. Horizontal siding – clapboard or weatherboard – usually covered the planks, although occasionally vertical battens were used where the planks were joined.

Heavy Timber Braced Frame Construction

Large heavy hewn timber joined with a series of mortise and tenon joints was another method of construction. For additional strength, each major portion of the structure was supported by a diagonal brace, also joined with a mortise and tenon cut.

Two Common Styles

The German central chimney plan had a deep fireplace dominating the kitchen, and a front door that was off center. Sometimes one story and sometimes two, these German-style houses ranged from two to four rooms in size.

The English I-house, was a simple and symmetrical rectangular two-story house, one-room deep, with internal chimneys in either gable end. The entrance was usually located in the center of the front facade.

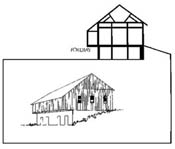

Pennsylvania Bank Barns

First built by German settlers, these barns have become an important symbol of Pennsylvania architecture. They were usually built into the side of a hill to give an entrance on two levels. The upper floor would allow vehicle access to be used for storing grain and hay, while the lower floor was used for housing animals. A cantilevered overhang or forebay, often facing south or east and supported by the extension of end walls, provided additional shelter from the weather to animals kept on the lower floor.

Georgian

Patterned after houses built in England during the reign of the three King Georges, formal versions of the Georgian style became popular for large homes in eastern American cities in the eighteenth century, with smaller and simpler versions built in rural towns, villages, and country settings. In Centre County, Georgian houses and vernacular versions were built throughout much of the nineteenth century, making Georgian one of the county’s most prevalent early styles. Pattern books provided local carpenters with examples and with details. At least a few early area houses appear to have been designed with Asher Benjamin’s popular American Builder’s Companion (1806) in use.

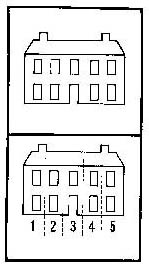

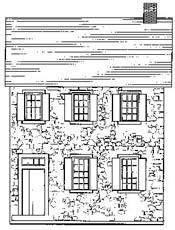

Georgian houses are symmetrical, well proportioned, rectangular in shape, and in some cases fairly formal in design. They are usually two stories; the ridge pole of their gabled roofs run parallel to the road. In Pennsylvania villages and towns these houses were commonly built close together and close to the street or sidewalk, with room for only a small front stoop or porch. Small barns or outbuildings are often found at the back of long, narrow village lots.

The standard room placement in these Georgian houses is four rooms to a floor, “four over four”, opening off a central hall, with interior chimneys at each of the outer or gabled ends of the house. Two story wings were commonly added to the rear, creating an L or T in the floor plan.

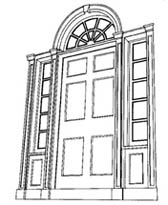

The entrance doorway is the chief feature of the front facade; windows are evenly spaced and directly in line with each other and the doorway, adding to the symmetry of these houses. Most often there are five windows or bays at the second level; two windows, a door, and another two windows at the first floor. The windows usually are double hung and often have six panes per sash.

Doors are almost always topped with a rectangular transom light or a more elaborate decorative fanlight arch. Shutters at the lower floor are most often paneled; the upper shutters are usually louvered.

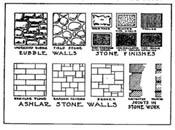

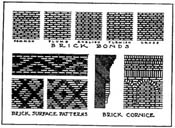

Centre County Georgian houses were built of hand cut field stone, wood, or brick. Sometimes the stone was roughly coursed, fitted in uneven shapes and sizes, sometimes laid in regular courses, and sometimes carefully square cut in an ashlar finish. Common, Flemish, and English bond brick patterns were used in double or triple widths throughout the county. Often English or Flemish bond were used for the front elevation of a house; common bond was used on the sides and back elevations.

Half Georgian – Row House

A common house-type variation is a half Georgian, a hall with two rooms arranged along one of its sides, as if one side of the house has been lopped off. The style is similar to a basic Philadelphia or Baltimore eighteenth century row house.

Federal

The Federal style, an American innovation incorporating classical details, is similar to the Georgian style in balance and symmetry and in proportion and decoration. It, too, first appeared in coastal cities, but eventually was adapted elsewhere in simpler or vernacular forms. Brick construction was common with flat arches or lintels used above the windows, and dentil molding added along the roofline. Low pitched gable roofs with stepped gable chimneys are common locally. A rectangular transom light made up of small panes or often an elliptical fanlight was added above the main entry door, and narrow windows or sidelights were placed at either side of a paneled door. The floor plan is very similar to the Georgian four over four. While city examples might have classical porticos, a simple porch is common for local examples.

Greek Revival

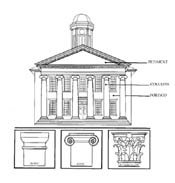

As Americans gained pride and confidence in their new Democratic government, they begin to link their ideals more closely with the democratic accomplishments of the ancient Greeks. The Greek Revival style, incorporating permanence, classical proportions and ornamentation, spread rapidly along the coast and into the frontier. Simple, orderly, and symmetrical in design and often painted white, buildings were turned so that their gable entrance faced the road. They were built to resemble Greek temples with columns, triangular pediments, and porticos or porches, triangular-shaped porch roofs supported by the columns. The style became especially popular for public buildings.

The Centre County Courthouse in Bellefonte is a good example. Originally a small limestone and brick building, it received its present front facade in 1835. Greek Revival also was used in a simplified form for smaller buildings. While the courthouse columns are large (each twenty-six feet), classical in style, and support the pediment, the simulated columns or pilasters on the former Methodist Church in Pine Grove Mills are flat against the surface of the building. The gable or pointed end of the building, rather than a porch roof, acts as the pediment. While the Greek Revival style was not common in Centre County for residential use, touches such as Greek porch columns, were occasionally added to Georgian houses.

The Victorian Age

The Victorian Age was an age of romanticism — a time of fascination with the whimsical, with the long ago and far away, and it soon caught the fancy of an increasingly confident society of Americans. Freedom of expression combined with imagination and nostalgia to create a lively, unconventional, complex series of architectural designs. Texture, color and asymmetry replaced the simplicity and the balanced symmetry of earlier architectural styles. The term “Victorian” refers to several styles rather than just one and reflects an entire period, roughly from the 1850s to the early 1900s in Centre County.

Because of an increased interest in architecture, house building became a subject of fashion. Prospective home owners could choose from a growing number of design options in illustrated pattern books and journals that sold like magazines. Centre County residents were no longer isolated by the mountains from the newest fashions; instead, aware of the latest in architectural styles they could use them for their own homes.

Gothic Revival

Architect Alexander Jackson Davis with his book, Rural Residences, and influential landscape gardener Andrew Jackson Downing with his enormously popular books, The Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture, and The Architecture of Country Houses, set the stage for an increasingly picturesque selection of housing types, villas and cottages specifically designed for the middle class.

A new method of construction — balloon framing — provided a strong skeleton on which walls could be hung. Lightweight wooden studs, joists, and rafters, supported by a foundation and sill, and fastened together with nails, were tightly woven together with each component strengthening the other. Siding was applied directly to the frame. Freed from the strict rectangular Georgian form used in the heavy framing technique, it was possible to construct complex, rambling houses using the balloon framing method, and by the end of the nineteenth century a balloon frame house was judged to be virtually the only kind of structure for a proper home.

Downing’s writings promoted national pride in America’s progress, and increased an American awareness of luxuries and refinements, domesticity and stability, architectural beauty and the beauty of the landscape. He specifically favored an architectural landscape that followed or promoted the modern or natural style of design over the formal and geometric arrangements of earlier styles, because he felt that turrets, towers, peaks, and the irregular form of the building and roofline blended better with the natural style — a landscape “where nature assisted in the creation of beautiful homes and gardens.”

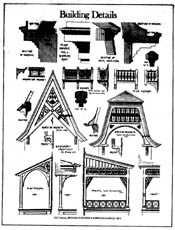

The “pointed” or Gothic style that he advocated introduced buildings that were taller, narrower, and less symmetrical. Steep roofs, peaks, often tall and pointed (lancet) windows, and sometimes board and batten siding were used to emphasize this vertical look. With the introduction of the jigsaw, and with millwork catalogs offering a variety of designs to select from, mass produced or sawn-to-order fanciful trim became available from lumber mills and local carpenters. Intricately cut decorative wood scrollwork, wood tracery, imitated the stone tracery of European Gothic buildings and took the name Carpenter Gothic. Gingerbread patterns varied from county to county and town to town, and similar patterns can even be found in iron fences and other iron work.

Gothic Revival became a popular choice for churches also, replacing the earlier Greek Revival style, built with tall steeples that “reached to heaven”.

Italianate

Victorian architectural pattern books offered a wide variety of Italianate or Italian Villa examples — rambling asymmetrical houses with generous porches or verandas, balconies, and often towers to simulate an Italian bell tower. Oversized decorative brackets placed under wide eaves, were made to look as if they were supporting nearly flat roofs. Arched or rounded tall, narrow windows and decorative corner quoining (large blocks used along the corners of the building) are other clues to this style. The Italianate style was often used for commercial buildings, such as the Bush House in Bellefonte.

Sometimes bracketing was added to older buildings, including ones built in the Georgian style, to “modernize” or decorate them.

Mansard – Second Empire

Victorians continued to experiment with architecture and by the 1870s introduced America’s version of a style from France. Called Mansard or Second Empire, it was named for its originator, French architect Francois Mansart.

The Mansard roof has a steep pitch, usually curved, and is flat or nearly flat. Dormer windows with pediments, used to light an attic story, often were inserted in the curve of the roof, and sometimes wrought iron tracery was added. Heavily molded entranceways, arched or pointed doors, and elaborate chimneys are other features of this style. A Mansard roof was often added to an Italianate style building along with balconies edged with ornate wood or cast iron railings, gables and eaves hung with gingerbread, rambling porches, and a variety of cupolas, towers, or turrets.

Queen Anne

Victorian architecture reached its peak of excitement with the style known as Queen Anne, the one that we think of most often when Victorian architecture is mentioned. It is the style whose motto could be “anything goes,” and often did! Queen Anne builders offered a flamboyant combination of facade variations, with patterned shingles and other building materials in a variety of colors and textures. Different roof shapes were combined with towers, turrets, and intricate chimneys. Spindles, brackets, curlicue cutouts, and other latticework was used for balconies and porches. Projecting bays and stained glass windows contributed to the exuberance of this style. Sometimes a decorative set of wood strips, called stickwork, was added to the wall surface to suggest the structural outline of the house.

Vernacular Victorian

Not all properties built during the last half of the nineteenth century were in such elaborate Victorian styles. Often they were built in more traditional styles with Victorian details, such as Gothic peaks or Italianate brackets, added to them. At the same time and with the urging of national tastesetters like Andrew Jackson Downing, decorative elements were being grafted onto or used to “dress up” older structures. Local carpenters were imaginatively updating houses with the additions of gingerbread trim and elaborate porches, such as those added to older Boalsburg and Rebersburg properties.

County House / Improved Country House

The Centre Furnace Mansion offers another example of what Downing might have considered “A Common Country House, Improved.” Originally an early five-bay brick in the Georgian style, the Centre Furnace Mansion underwent a major facelift soon after the Civil War. Roof dormers were enlarged and peaked to give height to the house; front windows were enlarged by lowering them to the floor; a large front porch topped by a balcony and decorated with gingerbread trim was added; decorative brackets were placed under extended roof eaves; and the bricks and trim were painted in a new color scheme that matched Downing’s recommendations that houses should be painted to be “in harmony with nature.”

Simplified versions of Victorian styles continued to be built into the twentieth century. Early properties along West College Avenue in State College, built between 1900 – 1910, offer an eclectic collection of elements from all of the various styles — Mansard and gabled roofs, classical porticos, multiple dormers, bays, towers, wrap-around porches, and other decorative details.

Early Twentieth Century Architecture

But, architecture in the new century increasingly began to move away from Victorian ornateness. Ushered in were ideas that focused on a simpler style and the use of pre-machine age “honest” materials, based on handicrafts and on decorative arts from the past. This was a conscious response to what England and eventually the American Arts and Crafts movement perceived as the negative effects of industrialized production and the distancing of workers from their crafts. Potential home owners were encouraged to become full participants in the planning and execution of their house designs in order to meet their specific needs. The house setting and its landscape surroundings also were considered important to the design.

Prairie Style

One of these new American styles of domestic architecture, originating in Chicago and the midwest before the first World War, was influenced by and reflected the Prairie School designs of Frank Lloyd Wright and his associates. These architects were attempting to define a truly American residential style, rather than one based on earlier European precedents. The style was low and horizontal, with low-pitched, hipped roofs, and overhanging eaves. These houses featured a simplicity in design and lack of ornamentation, and were meant to be open to air and light and to mirror the flatness of the prairies of the midwest. Built with non-traditional materials in a non-traditional style, they often were more expensive than most homeowners could afford and had limited popularity.

American Foursquares

Variations on the design, however, became very popular. The American Foursquare is a vernacular version of the Prairie School Style that was designed for a growing middle class market. It is a simple square two-story house with a low-pitched, hipped roof and widely overhanging eaves. Its centered or off-centered front entrance was the focal point of the front facade, and it often had a front and sometimes side-hipped dormers in its pyramid-shaped roof. The interior and exterior spaces of these houses were meant to be linked by a full-width first-floor front porch with massive, square porch supports.

Bungalows

The popularity of this style, found throughout Centre County and across the country, suggests that many buyers agreed with the 1923 mail-order catalog description by the Gordon- Van Tine Co. of Davenport, Iowa, “There is nothing that answers your purpose so well, if room is required, as the big, square house. The exterior is pleasing … The broad front porch with the big round columns, and the wide cornice, with the dormer, lend to the exterior the effect of greater breadth and height.”

While the Paririe Style originated in the midwest, the Bungalow Style’s popularity rapidly spread through published building plans east from California . These one or one-and-a-half story houses, while of limited size, were affordably priced and offered efficient and adequate space for a small family. Sloping roofs, held up by heavy supports, extended over large open front porches. An informal living room served as the core of the house, while the adjoining porch offered a sheltered space that was easily accessible to the yard and garden. Often built on modest-sized lots, these bungalows were set low to the ground and nestled in to blend with the landscape.

Craftsman Bungalows

The natural quality of materials and colors were emphasized in these larger variations of traditional bungalows — textured and ornamental stonework such as cobblestone, wood stained in earth tones, and finishes in stucco or shingles. Exposed roof beams, projecting rafters, and wooden roof supports also were used to highlight the natural, or “honest”, materials that were being offered in a simple and forthright way. Built-in furniture, and a large fireplace that was central to the house and its owners, are other characteristics of the Craftsman Bungalow style.

Historic Period Styles — Revival Styles

Classical themes and accurate interpretations of European styles became the basis for a third style of residential architecture across the country in the early part of the 20th century, reflecting a nostalgia for the past. Large and elaborate period houses, similar to those designed by architectural firms for wealthy clients in eastern cities, were designed in State College by area architects for national fraternity associations. In an eight-year period, 1925-1933, more than twenty such houses of between 7,000 and 15,000 square feet were built, mirroring historic examples, many on large lots with appropriate landscaping. They provide significant examples of Colonial Revivial, Neoclassical, Tudor Revival, and other historic styles.

At the same time, smaller period-style houses were being built in State College, Bellefonte, and elsewhere in the County offering a wide historical spectrum of European and Colonial American housing styles. While occasionally built with correct proportions and details that reflected the historic accuracy of earlier buiildings, more often these smaller houses borrowed designs or motifs to suggest a specific style. They were designed to be both practical and artistic, combining modern convenience with comfortable living. They were generally built of wood frame construction, but often were finished with stonework or brickwork exteriors using new and inexpensive methods for adding veneers. Gardens and landscape settings continued to be important considerations to new home owners.

Colonial Revival

Early twentieth century Colonial Revival-style homes mirror many of the features of their Georgian-style predecessors — two stories in height with the ridge pole running parallel to the street, a symmetrical front facade with an accented doorway and evenly spaced windows on either side of it. But there are specific features that identify them as twentieth century houses rather than those dating from the early 1800s. They included extra elaborate front doors, often with decorative crown pediments and overhead fanlights and sidelights, but with machine-made woodwork that had less depth and relief than earlier handmade versions. Window openings, while symmetrically located on either side of the front entrance, were usually hung in adjacent pairs or in triple combinations rather than as single windows. Side porches or sunrooms were common additions to these homes, introducing modern comforts to an earlier housing style.

Dutch Colonial

The use of gambrel roofs, unique with Dutch Colonial houses, was influenced by and captured the spirit of the early Dutch homes of New York State. Large, long shed dormers ran parallel to the roof’s ridge line on both the front and the rear of these buildings. The use of mixed facade materials was characteristic with the Dutch Colonial style — stone or brick veneer for the first floor, with wooden shingles or stucco for the upper story. Other style features included paired windows with window boxes, shutters, a small porticoed front entrance, and a side sunporch. According to architects of the period, this style was popular because of its modern features, multiple rooms, vestibules, and a simple approach to decoration. The Dutch Colonial house peaked in popularity in the 1920s; examples are still evident in older residential neighborhoods across the country. A popular mail-order style, Sears Roebuck & Co. had more than twenty-seven different models.

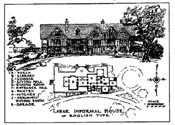

English Tudor Revival

Based on late nineteenth century Tudor cottages of the English countryside, this popular American style of the 1920s and 1930s ranged from large, rambling, asymmetrical, and historically accurate fine country estates to tiny picturesque cottages. Large versions with superior detail and distinctive massing are well represented in State College’s fraternity district, and in a few unique single family county homes. Characteristic features included a steeply pitched slate roof with steep cross gables; a combination of coursed (layered in horizontal rows) rubblestone, brick, and stucco covering the frame construction of the building; massive, sculptured front chimneys; half-timbering decoration between brickwork to enhance the design; carved stone entrances, thick wooden doors, wrought iron hardware; and tall, narrow windows or long rows of leaded and diamond paned casement windows.

English Cottages

Many of the same details, but on a much smaller scale, were used in the design of single family houses in the English Cottage style. Sharply pitched slate roofs, steep gables, large front chimneys, stone veneer finishes, and stucco and decorative half-timbering were used to emphasize the characteristics of English Cottage architecture. Sometimes even false thatched roofs were used to enhance the cottage look.

International Style – Moderne

Rather than the ornament of the English Tudor style, the modern home favored reinforced concrete and glass to emphasize formal composition and add decorative effect. American modern architecture merged with Europe’s International Style to produce examples of Moderne dwellings that were simple with plain wall surfaces. Materials for these geometrically shaped buildings, often with Art Deco elements, included cinder blocks, poured concrete, stucco, steel framing, and glass blocks.

Mail-Order Houses

Since the mid-nineteenth century, lumber companies had been in the business of providing dimension lumber like two-by-fours, and other materials for home building — siding, shingles, doors, and windows with pre-framed sashes. Midwestern companies that had been selling and shipping boxcar trainloads of housing materials to local lumber yards, took on new names and marketing plans and became mail-order companies called Aladdin, Lewis Homes, Liberty Homes, and Gordon-Van Tine. They were quickly joined by mail-order giants Sears, Roebuck and Co. and Montgomery Ward who expanded their offerings by entering the mail-order housing business.

County residents could select total house packages with first-rate materials in the latest style choices to meet their space needs, budgets, and their specific tastes. Building parts arrived by railroad, precut and numbered. Sears also offered household furnishings to enhance the design, along with a mortgage plan to help owners acquire their new homes. It included a guarantee that promised satisfaction or Sears would pay all shipping costs and refund the purchase price.

Once the lot and foundation were ready, the homes were assembled by local builders or possibly even by the purchasers themselves. Shipping dates were staggered so that materials arrived by train as needed, with supplies coming not only from Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but from midwest locations as well. In some cases, local contractors were engaged by Sears and construction was supervised by a company representative.

In styles offering variety and distinctiveness that ranged from Prairie Style Foursquares to small Bungalows, and from picturesque English Cottages to formally detailed Colonial Revivals, these individually selected, well-designed, and well-built twentieth century homes can be found throughout Centre County.

How can you tell if yours is a mail-order house? Matching styles to old catalogs or books about them is one way. Original bathroom and kitchen fixtures and hardware may have a company name printed on them, and numbers on joists or rafters used in construction offer other clues.