- What is a sampler?

- Distinct Needlework from Pennsylvania Academies

- Elements of the Quaker Sampler

- Motifs of Miss Sarah Tucker

- PA German Influence

- Preserving Your History

- Photos

- Exhibition Booklet PDF

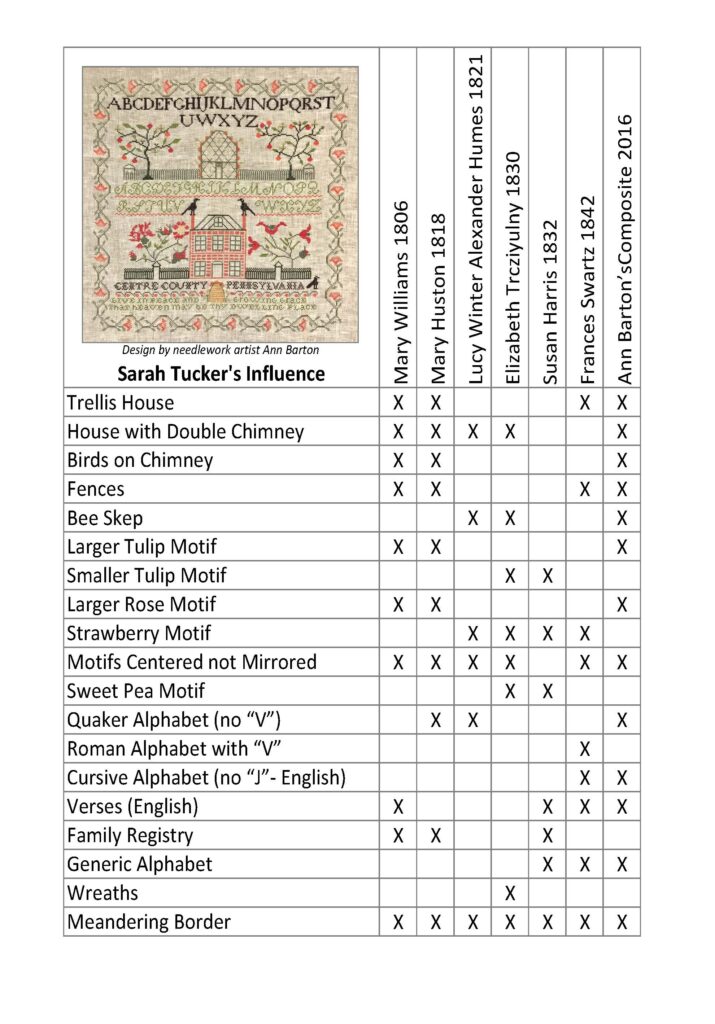

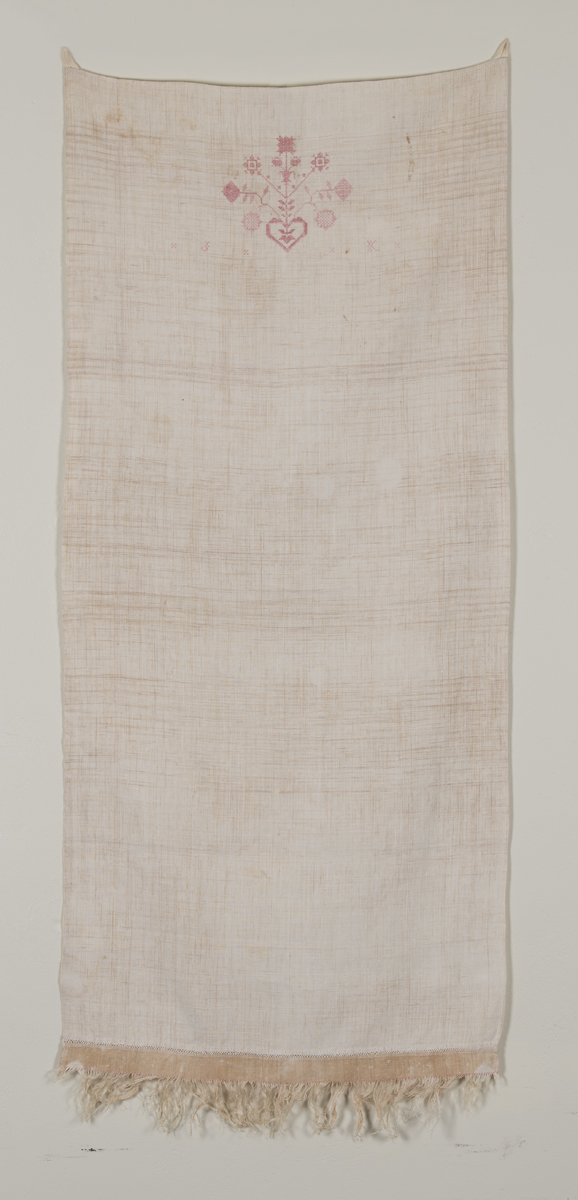

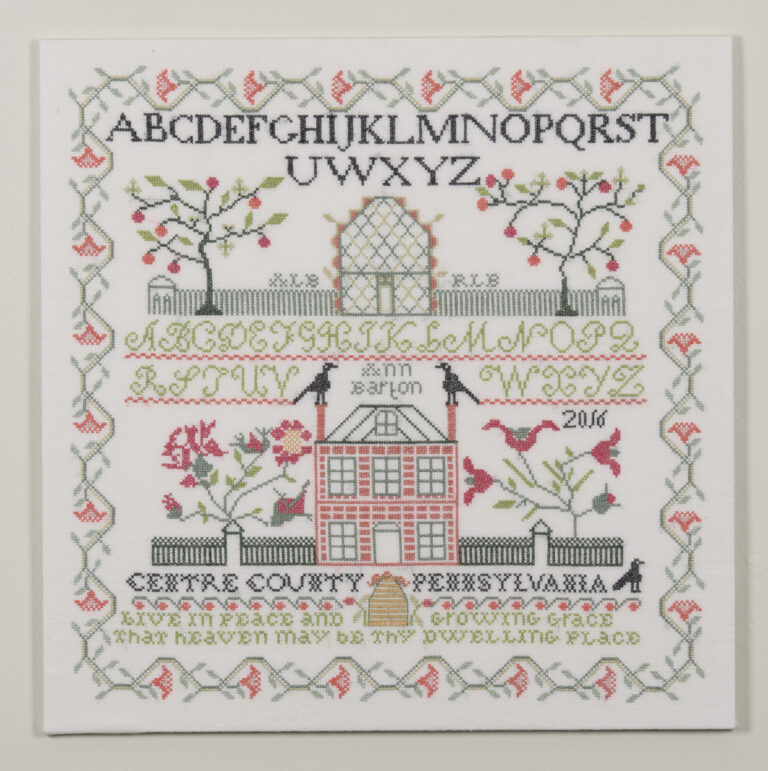

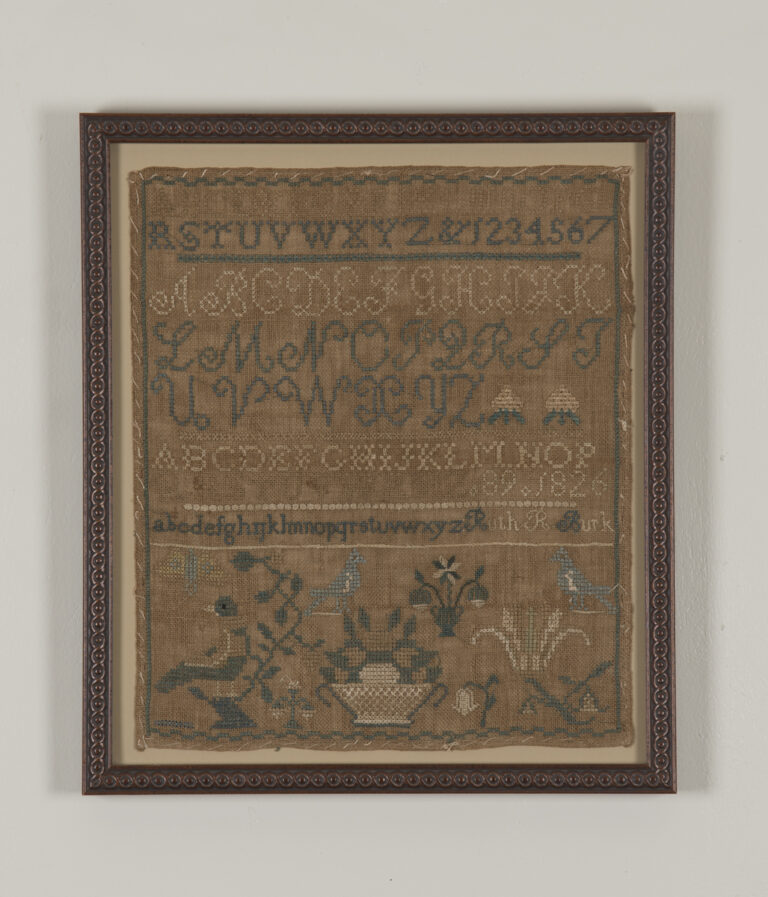

Objects like samplers and fraktur often hold important historical context and family history. Examples in the exhibition are from Centre County, and more broadly Central PA for the most part. The samplers [or images of samplers] on the title wall are all examples from Bellefonte sampler makers who are believed to have studied under needlework teacher Sarah Tucker. Committee member, Ann Barton, designed and created a “Centre County” sampler that pulls together elements that are common to these examples.

The samplers that were in the exhibition Unraveling the Threads of Time are listed on the Sampler Archive Project website.

WHAT IS A SAMPLER?:

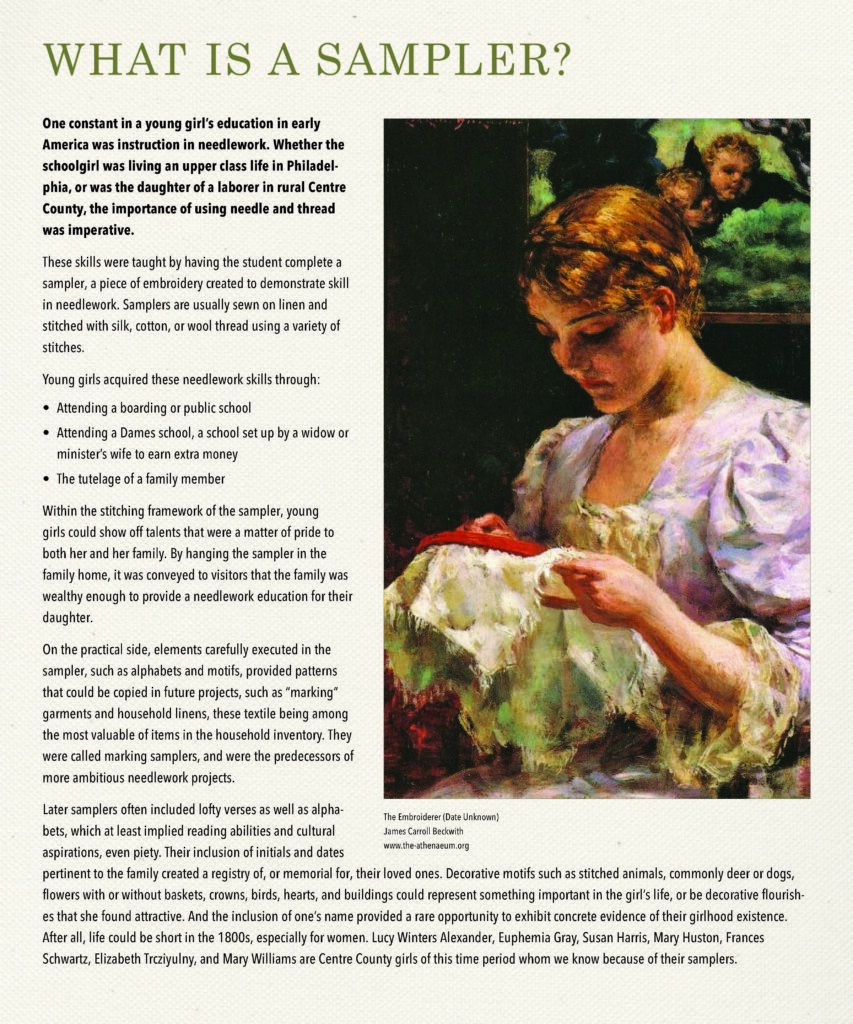

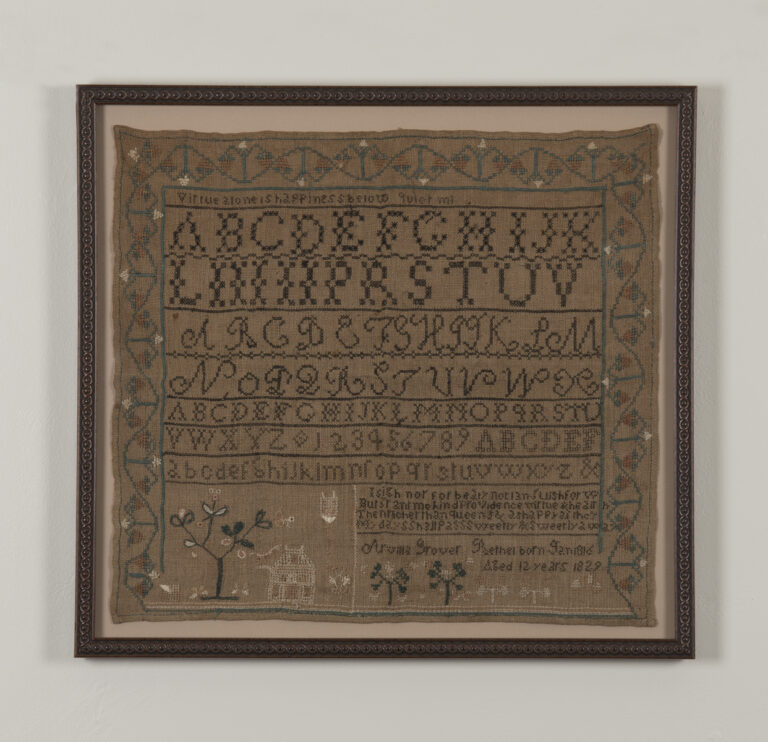

One constant in a young girl’s education in early America was the instruction of needlework. Whether the schoolgirl was living an upper class life in Philadelphia, or was the daughter of a laborer in rural Centre County, the importance of using needle and thread was imperative.

These skills were taught by having the student complete a sampler, a piece of embroidery created to demonstrate skill in needlework. Samplers were usually made on linen and stitched in silk with various stitches. Young girls could acquire these needlework skills through:

- Attending a boarding or public school

- Attending a Dame’s school , a school set up by a widow or minister’s wife for a few weeks to earn extra money

- The tutelage of a family member

Within the stitching framework of the sampler, young girls could show off talents that were a matter of pride to both her and her family. By hanging the sampler in the family home, it was conveyed to visitors that the family was wealthy enough to provide a needlework education for their daughter. On the practical side, elements carefully executed in the sampler, such as alphabets and motifs, provided patterns that could be copied in future projects, such as “marking” garments and household linens, among the most valuable of items in the household inventory. They were called marking samplers, and were the predecessors of more ambitious specimens.

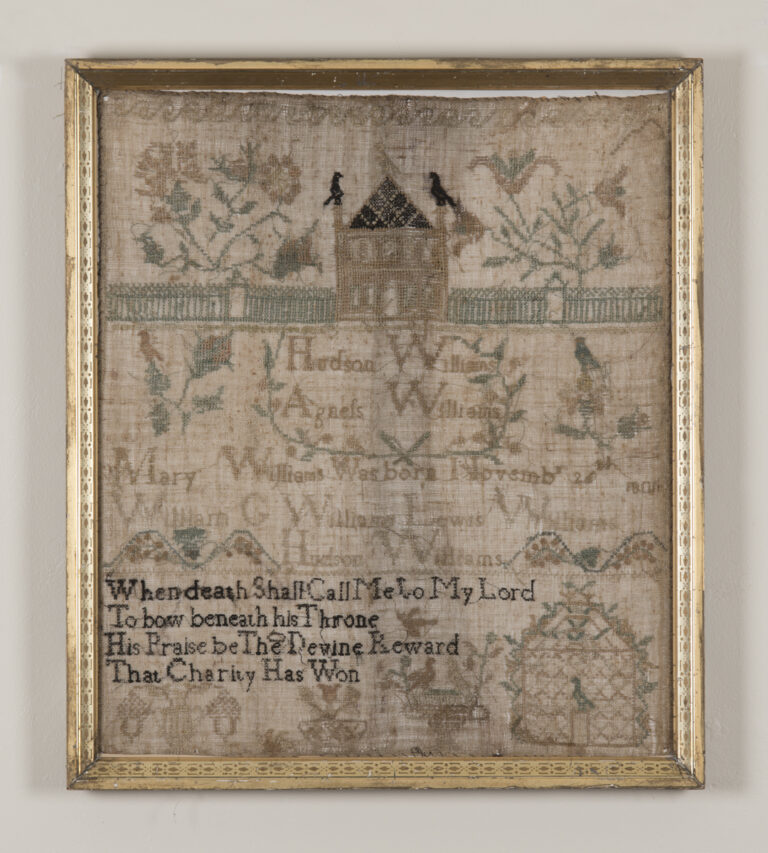

Later Samplers often included lofty verses as well as alphabets, which at least implied reading abilities and cultural aspirations, even piety. Their inclusion of initials and dates pertinent to the family created a registry of, or memorial for, their loved ones. Decorative motifs such as stitched animals, commonly deer or dogs, flowers with or without baskets, crowns, birds, hearts, and buildings could represent something important in the girl’s life, or be decorative flourishes that she found attractive.And the inclusion of one’s name provided a rare opportunity to exhibit concrete evidence of their girlhood existence.After all, life could be short in the 1800s, especially for women.Lucy Winters Alexander, Euphemia Gray, Susan Harris, Mary Huston, Frances Schwartz, Elizabeth Trcziyulny, and Mary William are Bellefonte girls of the period that we know because of their samplers.

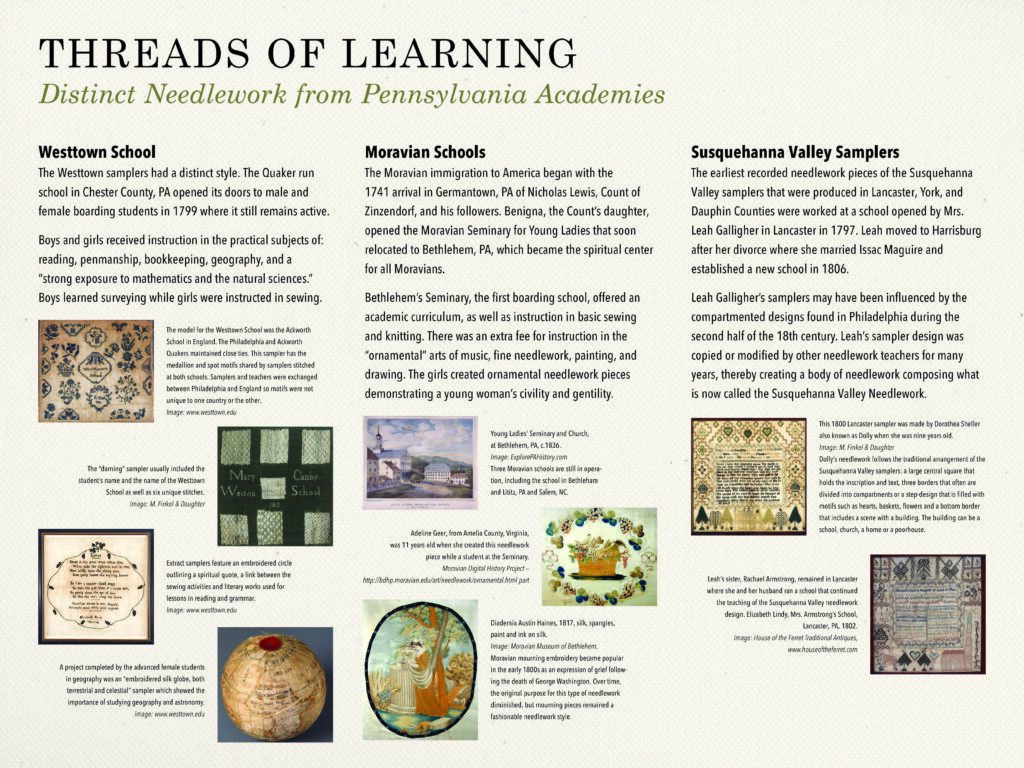

Westtown School Samplers

The Westtown samplers were a distinct style of sampler created by female students at the Quaker run Westtown School that opened its doors to male and female boarding students in 1799. Today, the still active Westtown boarding school, purchased in 1794, is located in Chester County, PA. In the early years, boys and girls received instruction in the practical subjects of: reading, penmanship, bookkeeping, geography, and a “strong exposure to mathematics and the natural sciences.” Boys learned surveying as well as, samplers and fabric globes.

The model for the Westtown School was the Ackworth School in England. The Philadelphia and Ackworth Quakers maintained close ties. This sampler (right) has the medallion and spot motifs shared by samplers stitched at both schools. Samplers and teachers were exchanged between Philadelphia and England so motifs were not unique to one country or the other. Two other forms of Westtown samplers were the darning sampler and the extract sampler. The darning sampler usually included the student’s name and the name of the Westtown School as well as six unique stitches.

Extract samplers feature an embroidered circle outlining a spiritual quote, a link between the sewing activities and literary works used for lessons in reading and grammar. A project completed by the advanced geography female students was an “embroidered silk globe, both terrestrial and celestial” sampler which showed the importance of geography and astronomy was to the student’s curriculum.

Moravian Needlework

Bethlehem’s Moravian Seminary for Young Ladies was the first acclaimed girls’ boarding school in the country. In December 1741, Nicholas Lewis, Count of Zinzendorf, his daughter, Benigna, and a small band of followers arrived in Germantown. Benigna opened a school for twenty-five students in Germantown on May 4, 1742. The school moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania which became the spiritual center for all Moravians in the New World.

Young Ladies’ Seminary and Church, at Bethlehem, PA, circa 1836.

A broad academic curriculum was taught including arithmetic, botany, French and German, geography, reading, writing, essential sewing and knitting while the “ornamental” arts of music, fine needlework, painting, drawing were taught for additional fees. The girls educated at the Moravian Seminary went beyond utilitarian needlework such as “marking” samplers to produce wonderful ornamental needlework pieces; a typical 1815 piece has a central motif surrounded by a branching fruit, floral, or ribbon motif. Accomplishments in the fine arts was considered evidence of a young woman’s civility and gentility. Adeline Geer, from Amelia County, Virginia, was 11 years old when she created her needlework piece while a student at the Seminary.

In 1748, the Linden Hall Seminary, a second Moravian girls’ school, was opened and later moved to Lititz. The Bethlehem and Lititz curriculum and embroideries were similar.

The third Moravian seminary was established in 1802 in Salem, North Carolina. Two years later, the Salem Girls Boarding School accepted the first non-Moravian students.

Following the death of George Washington, and as an expression of grief, Mourning Embroidery became popular in the early 1800’s. Over time, the original purpose for this type of needlework diminished and mourning pieces became a fashionable needlework style.

Diademia Austin Haines, 1817, silk, spangles, paint and ink on silk, Moravian Museum of Bethlehem.

Today, all three of the Moravian schools located in Bethlehem, Lititz, and Salem College (near historic Old Salem, NC), are still in operation.

Susquehanna Valley Samplers

The earliest recorded needlework pieces of the Susquehanna Valley samplers that were produced in Lancaster, York, and Dauphin Counties between 1797 and 1838 were worked at a school opened by Mrs. Leah Galligher in Lancaster in 1797. Leah Galligher (later Maguier or Maquire) may have been influenced by the compartmented designs found in Philadelphia during the 2nd half of the 18th century. Leah’s design was copied or modified by other needlework teacher’s for many years, therefore, creating a body of needlework composing what is now called the Susquehanna Valley Needlework. Leah moved to Harrisburg after her divorce where she married Issac Maquire and established a new school in 1806.

Leah Galligher’s school, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1800

The 1800 Lancaster sampler above was made by Dorothea Sheller also known as Dolly when she was nine years old. Dolly attended Leah Galligher’s school and two years later she worked a second sampler. She died in 1867 and in her will specifically mentions her samplers. Dolly’s needlework follows the traditional arrangement of the Susquehanna Valley samplers: a large central square that holds the inscription and text, three borders that often are divided into compartments or a step-design that is filled with motifs such as hearts, baskets, flowers and a bottom border that includes a scene with a building. The building could have been a school, church, a home or a poorhouse.

Leah’s sister, Rachael Armstrong, remained in Lancaster after Leah moved to Harrisburg. Rachael and her husband continued teaching school subjects and needlework. (Image: Elizabeth Lindy, Mrs. Armstrong’s School, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1802)

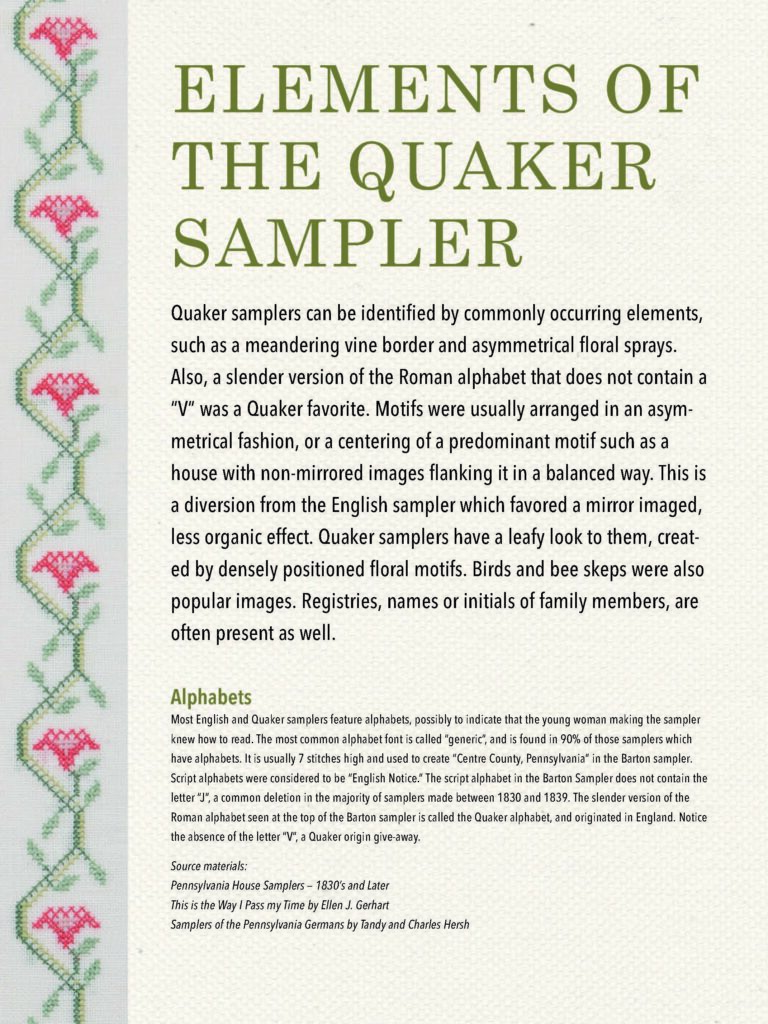

Elements of the Quaker Sampler

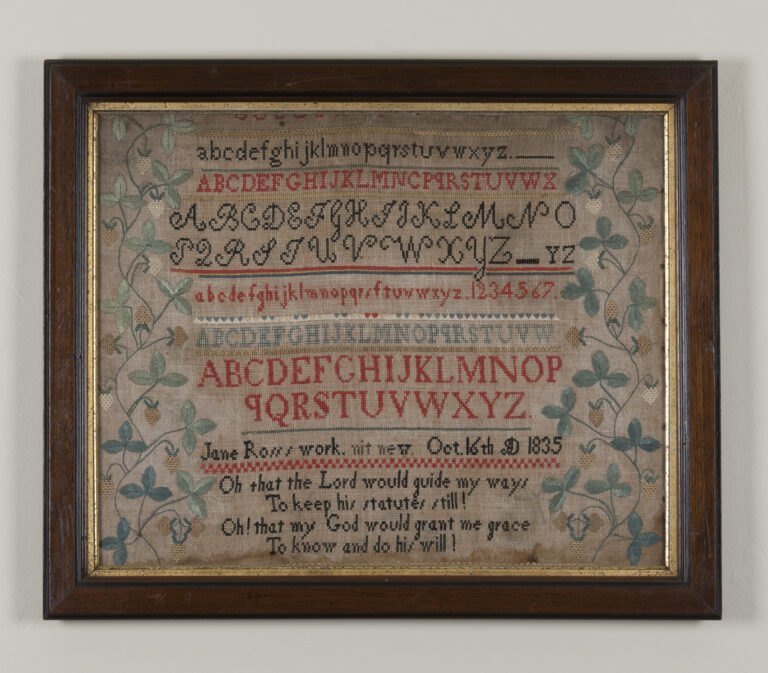

Quaker samplers can be identified by commonly occurring elements, such as a meandering vine border and asymmetrical floral sprays. Also, a slender version of the Roman alphabet that does not contain a “V” was a Quaker favorite. Motifs were usually arranged in an asymmetrical fashion, or a centering of a predominant motif such as a house with non-mirrored images flanking it in a balanced way. This is a diversion from the English sampler which favored a mirror imaged, less organic effect. Quaker samplers have a leafy look to them, created by densely positioned floral motifs. Birds and bee skeps were also popular images. Registries, names or initials of family members, are often present as well.

Alphabets and Verse of the Barton Sampler

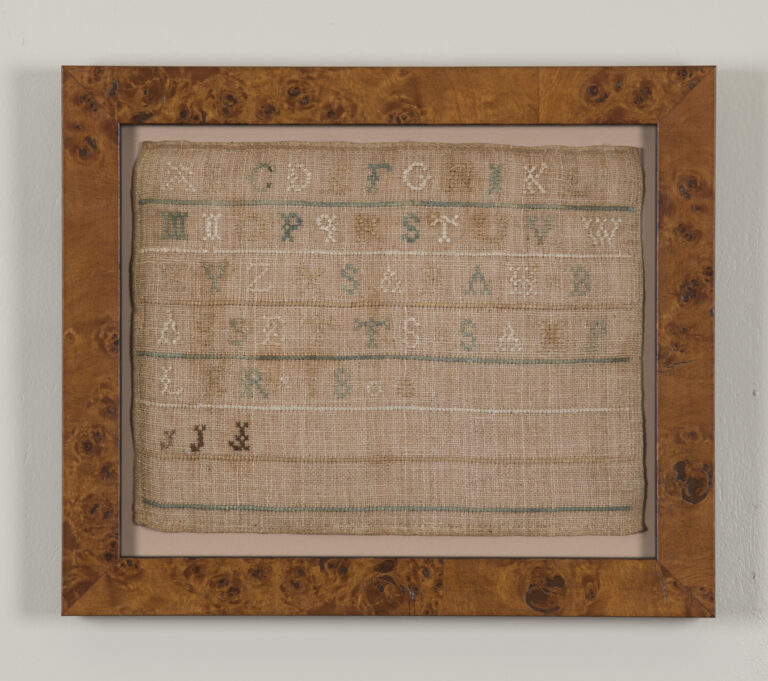

Alphabets are often a predominant feature of samplers, possibly to indicate that the young woman making the sampler knew how to read.

The slender Roman alphabet found at the top of this sampler was a favorite of the Quakers. Notice that there is no “V”, a common omission of the time.

The Script or Cursive alphabet, most likely English in origin, is located directly under the trellis house motif.

Alphabets in samplers made between 1830 and 1839 often did not include the letter “J”. This was the case of the German alphabet of the time and could explain why this omission occurred. The Script alphabet found under the trellis house on the Barton sampler follows the “no J” tradition. The seven stitches tall Generic alphabet represented 90% of all alphabets used in samplers of the time. The “Centre County Pennsylvania” line of the Barton sampler is an example of the Generic style.

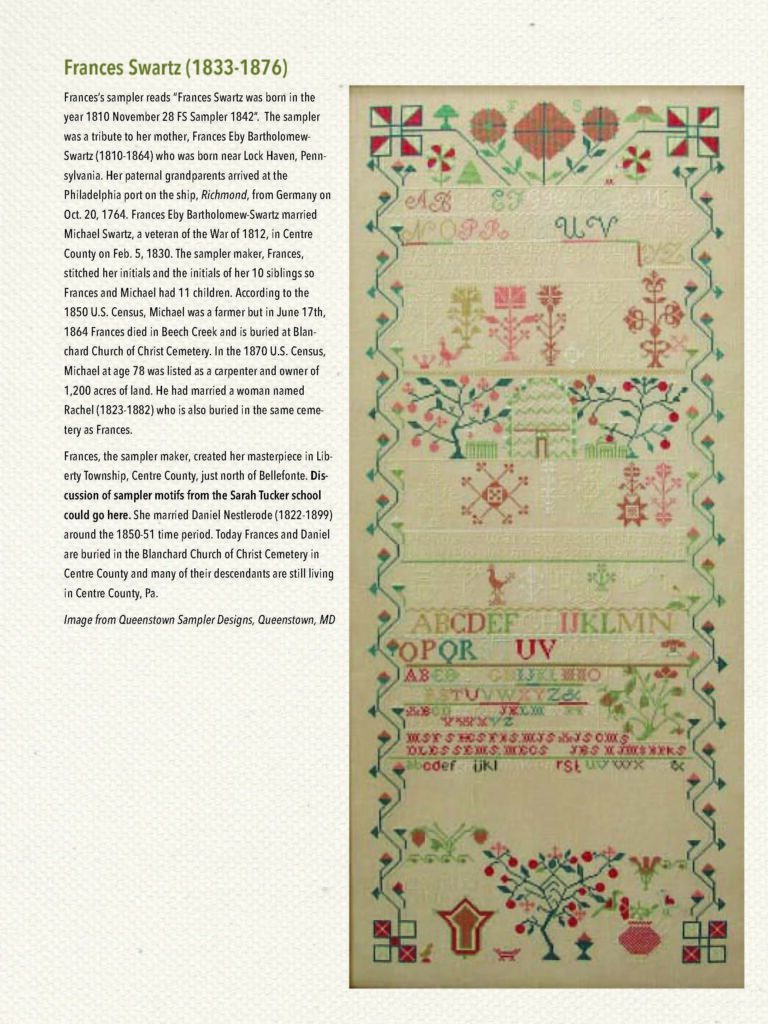

The verse on the Barton sampler represents a component found on most school girl’s samplers. Verses were taken from biblical text or poetry. They were often a part of the English sampler, reflecting a centuries old tradition of depicting higher social status by including lofty sayings. The piety of the sampler maker might also be an implied effect of the verses. This particular verse can be seen on the Frances Swartz sampler, as seen in this exhibit.

Miss Sarah Tucker, a Quaker, was a “subscription school” teacher in Bellefonte who had a profound influence on the needlework of some young women who lived in Bellefonte. She was one of the earliest teachers who, by 1807, had already been teaching for some time. In the History of Centre and Clinton Counties, PA 1883 by John Blair Linn, Sarah was reported to have been a popular teacher who taught for around twenty years ending her career about 1825. The “Centre Democrat” listed Miss Tucker’s death on May 20, 1836 at 92 years.

Miss Tucker, as most needlework teachers, had a repertoire of preferred designs. She combined her favored motifs with those associated with the Quakers to create a unique Centre County look. We are very pleased to present six Bellefonte schoolgirl samplers that bear the Sarah Tucker signature motifs (see Sarah Tucker’s Influence chart) along with classic Quaker elements. The needlework samplers on the following wall were worked by students of Sarah Tucker and include works by: Mary Huston, Lucy Winters Alexander (Humes), Mary Williams, Elizabeth Trcziyulny, Sarah Trcziyulny, and Susan S. Harris.

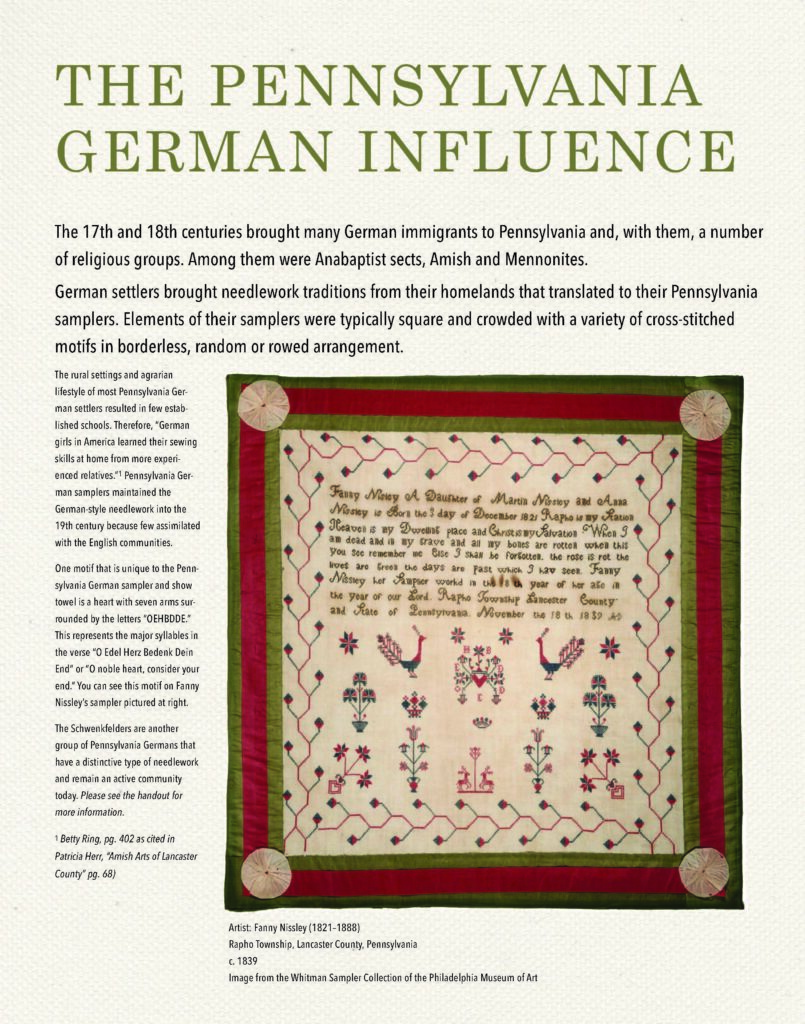

The Pennsylvania German Influence:

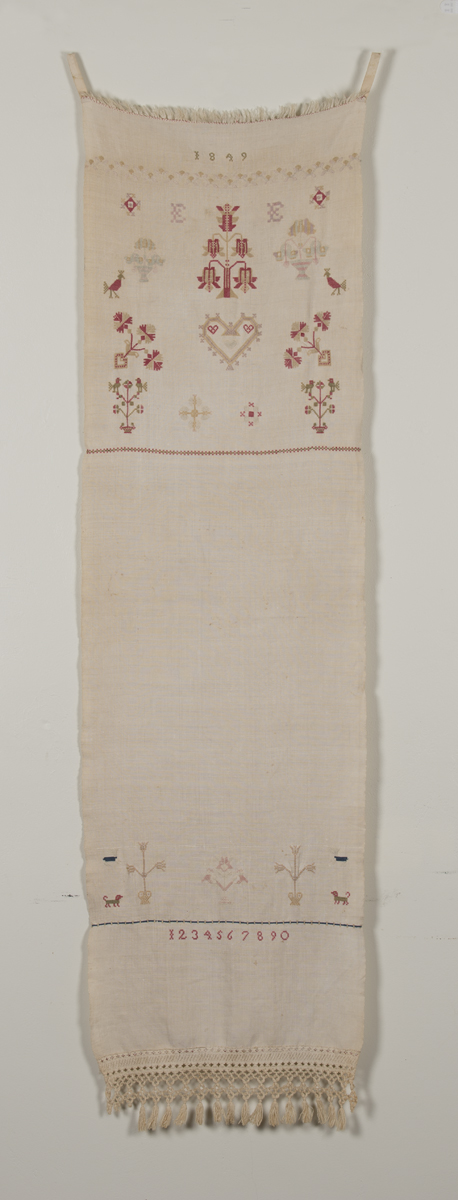

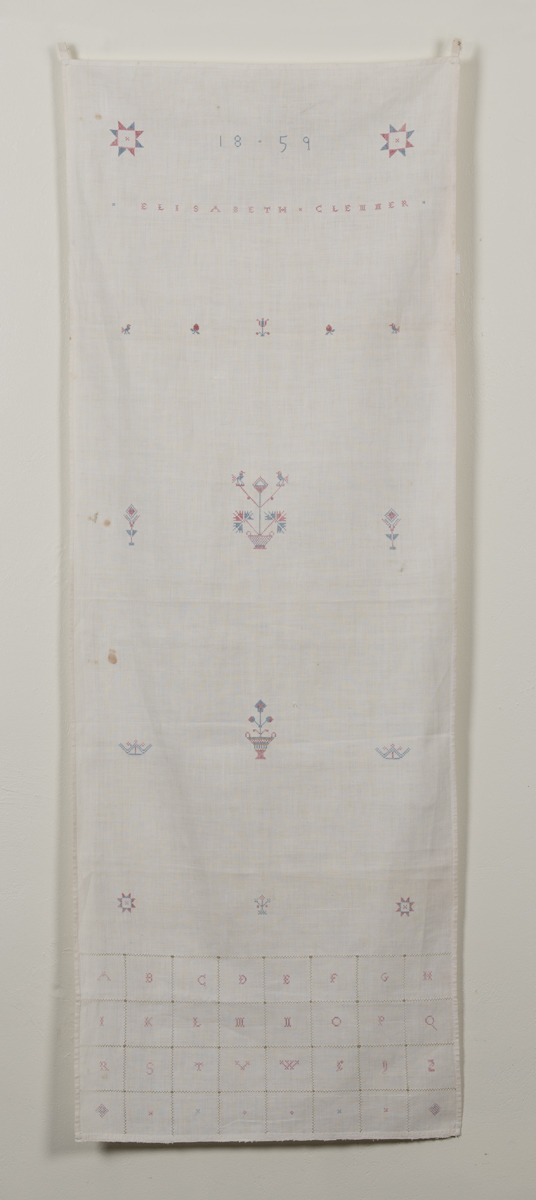

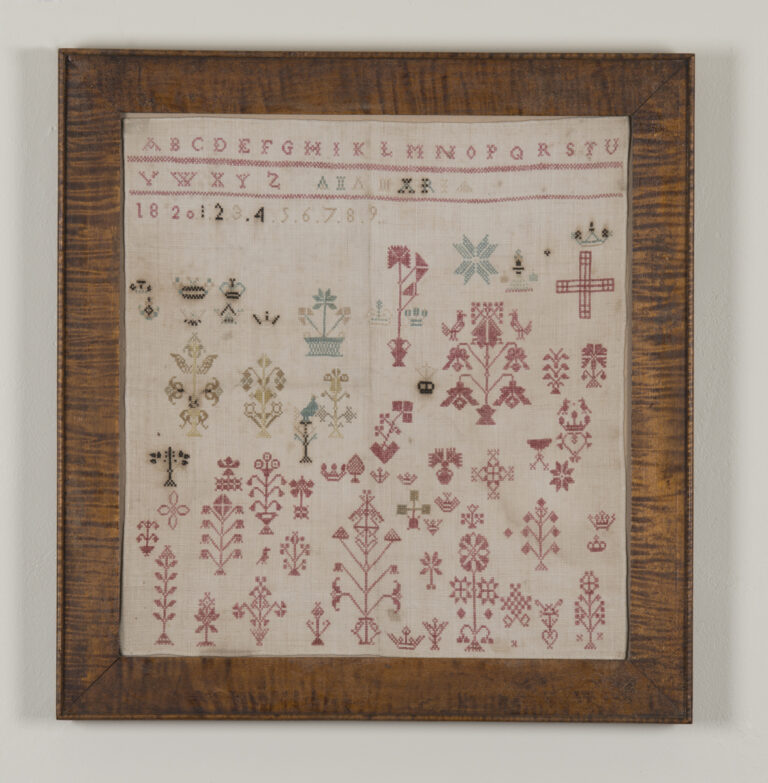

During the late 17th and early 18th century, there was a large influx of German immigrants into Pennsylvania, including numerous religious groups such as the Moravians, Schwenkfelders, Lutheran, Calvinists, Dunkards, and Anabaptist sects, primarily, the Amish and Mennonites. These settlers brought the needlework traditions from their homelands. Therefore, their Pennsylvania samplers were similar to traditional German needlework being typically square and crowded with a variety of cross-stitched motifs in borderless, random or rowed arrangement.

The rural settings and agrarian lifestyle of the majority of Pennsylvania German settlers resulted in few established schools. Therefore, “German girls in America learned their sewing skills at home from more experienced relatives” (Betty Ring, pg. 402 as cited in Patricia Herr, “Amish Arts of Lancaster County” pg. 68). The Pennsylvania German samplers maintained the German-style needlework into the 19th century because the communities were insular and few assimilated with the English communities.

One motif that is unique to the Pennsylvania German sampler and show towel is a heart with seven arms surrounded by the letters OEHBDDE. This represents the major syllables in the verse O Edel Herz Bedenk Dein End or “O noble heart, consider your end”. You can see this motif on Fanny Nissly’s sampler (Image left) and is located in the Whitman Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Schwenkfelder:

The Schwenkfelders are one group of Pennsylvania Germans. They emigrated in 1733 from Silesia to Pennsylvania where they established a still active community and churches. (American Folk Art Museum).

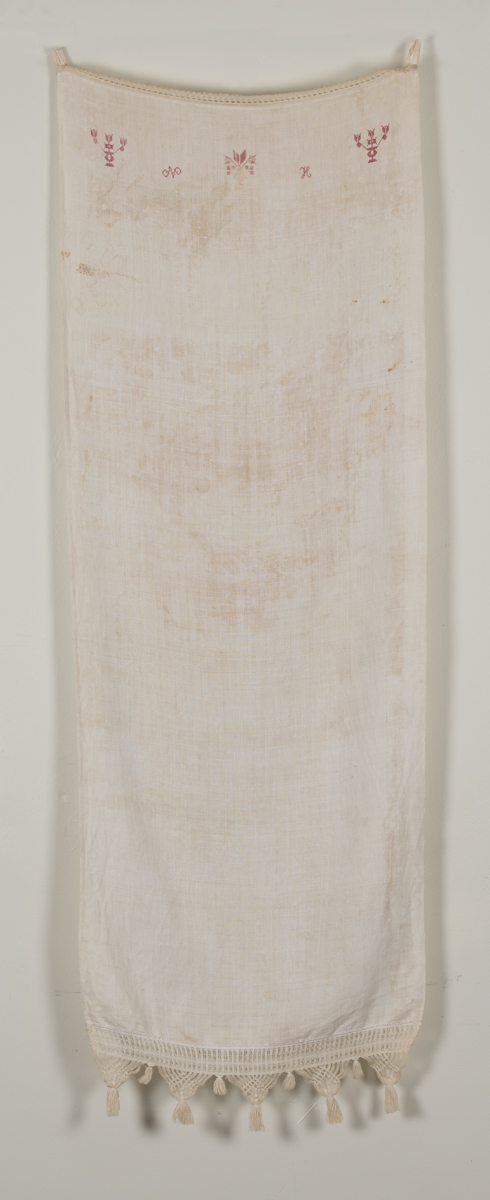

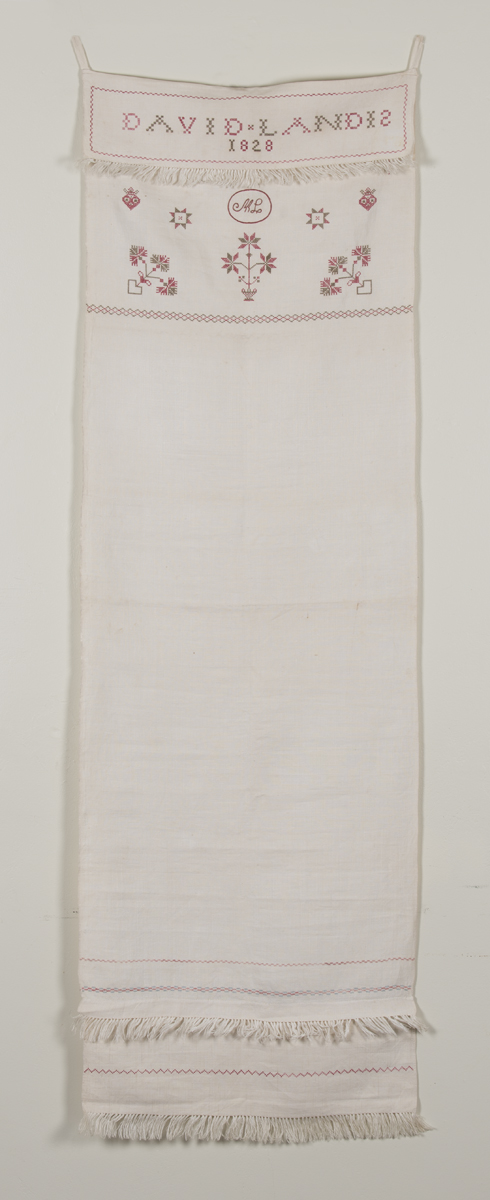

A Schwenkfelder girl first learned at home how to make a sampler from the women in her family, copying motifs from her relative’s work. Several years later, the young woman completed a decorated show towel, the decorated towel displayed her finest needlework skills. (Clark Hess“Mennonite Arts”) The show towel was hung over a plain hand towel on a door to decorate the home.

Distinguishing characteristics of Schwenkfelder samplers:

- A Schwenkfelder sampler can be distinguished from other Pennsylvania German samplers by the unique motifs, as found in the sampler below.

- Cartouche – found below the man on sampler

- Crown with three diamonds – found on the bottom half of the sampler to the right of the date

- Three carnations – found above larger crown

- Star with the double cross – found to the right of the carnations

- Another difference is that the Schwenkfelder samplers use a variety of embroidery stitches such as the chain stitch, double-back stitch, and geometric satin stitch, (Alyssum) in addition to the cross stitch.

- The alphabet is of a Germanic type.

Schwenkfelder needlework did not use: a set of numbers after the alphabet, the German script alphabet, the peacock motif, with few exceptions, the use of the OEH motif, and wide borders.

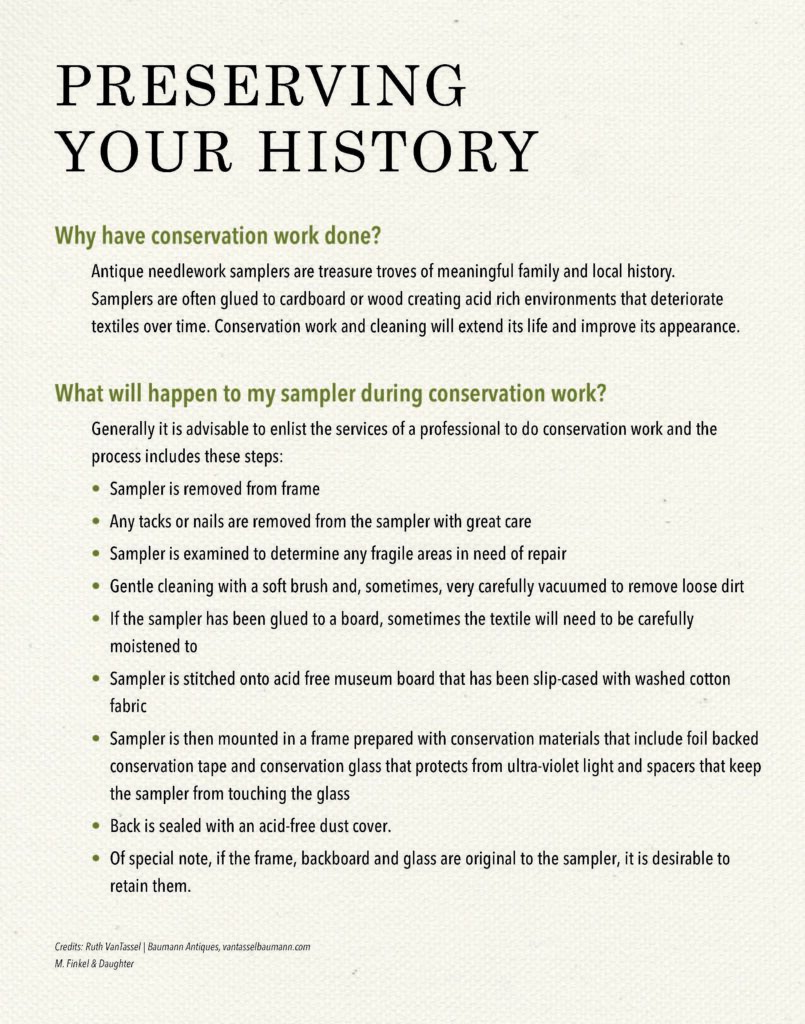

PRESERVING YOUR HISTORY

Why have conservation work done?

Antique needlework samplers are treasures of family and local history worth preserving. Conservation work and cleaning will improve the appearance and extend the life of your sampler.

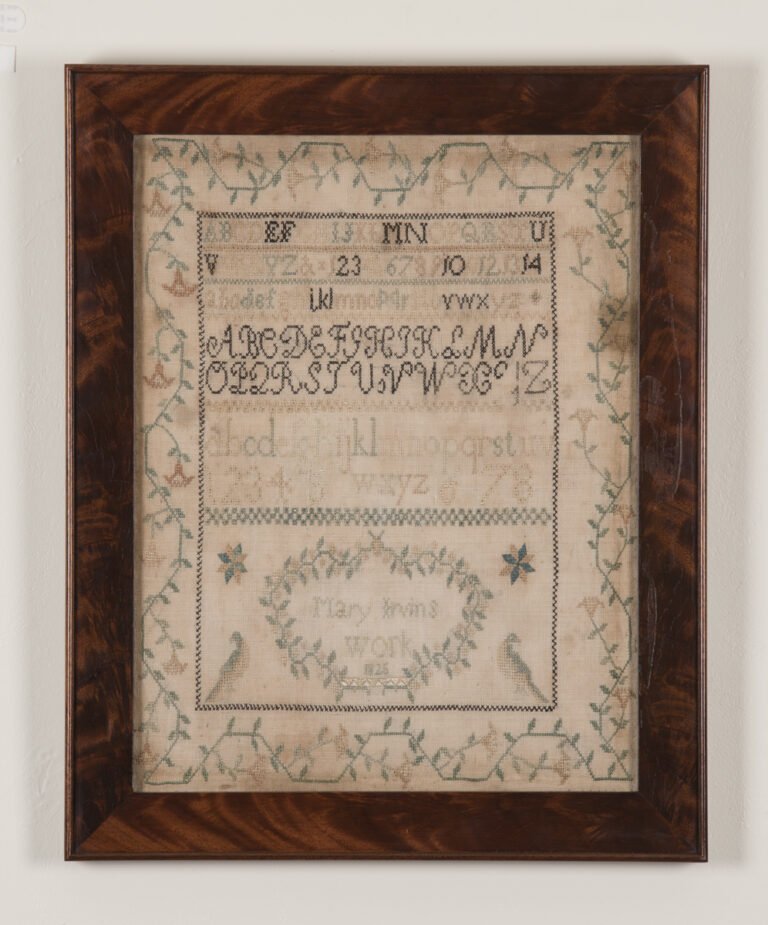

Mary Irvin’s school girl sampler on display was completed at age 13. Moses Thompson later married Mary Irvin and they lived at the Centre Furnace Mansion from 1842 to 1891. Thompson family descendants donated Mary’s sampler to the Centre County Historical Society and conservation work on it was done professionally.

The border design on Mary Irvin’s sampler was wrapped onto the backing to fit into a smaller frame. The sampler was reframed in a more size appropriate period style frame.

The staining was not all removable in conservation, but the appearance of the sampler was improved and it is now preserved for future generations of Thompsons and visitors to the Centre Furnace Mansion.

What will happen to my sampler during professional conservation work?

The intricacies and extent of conservation work will vary depending on what is needed and its historic and monetary value. A conservator will examine the sampler and prepare a plan for its conservation and every step will be carried out with great care.

After the frame is removed, any tacks or nails that may have been used to fasten the sampler to its backing will be removed. Samplers are often glued to an acid rich cardboard or wood backing that damage textiles over time. After removal from its backing, cleaning may range from a simple dusting with a soft brush, and gentle vacuum to a more involved water or dry cleaning process.

The finished sampler is then stitched onto acid free museum board that has been slip-cased with washed cotton fabric. Framing is done with ultra-violet conservation glass separated from the sampler with spacers. The back is sealed with an acid-free dust cover.

Credits:

Ruth VanTassel | Baumann Antiques, www.vantasselbaumann.com

M. Finkel & Daughter | Samplings, www.samplings.com

Click on an image to enlarge.