Limestone has played an essential role in Centre County’s economic history. Widely used for both industrial and agricultural purposes, limestone has been mined in the county for more than 200 years.

Millions of years ago, part of what is today Centre County was overlain by a vast seabed. Oysters, clams, coral, and similar ocean-dwelling organisms used calcium carbonate (CaCO3) found in seawater to create their shells and bones. As those organisms died, their remains settled on the ocean floor, where over time they were compacted into a layer of sedimentary rock that is known as limestone.

While limestone is found worldwide, Centre County’s deposits are exceptionally pure. It is ideal for the manufacture of lime, which in its simplest form is a process of applying extreme heat to crushed limestone in order to drive off carbon dioxide (CO2) and other impurities, leaving behind calcium oxide (CaCO) or lime. With fewer impurities to be driven off, the result is a more efficient calcining process and a higher quality end product.

The Bellefonte ledge of limestone—as much as 97-99 percent calcium carbonate—lies in a vein 35-90 feet thick sloping 45-90 degrees under the eastern shoulder of Bald Eagle Ridge. Other generally less pure deposits lie in a roughly horizontal vein under the western shoulder of Nittany Mountain and parts of Penns Valley.

As a flux in the county’s early blast furnaces, limestone combined with impurities in the iron ore during the smelting process and was then drawn off as slag. Lime also was used as a purifier in making iron; and when mixed with cement and sand, lime added strength to the resulting mortar. Farmers burned limestone in primitive pyres and used the residual lime to “sweeten” acidic soils.

William Shortlidge (1831-1890) was first to market lime beyond Centre County. In 1863, after consulting Penn State president and pioneer agricultural chemist Evan Pugh, who verified the exceptional quality of the Bellefonte ledge, Shortlidge sold lime to the Pennsylvania Railroad for use in constructing a passenger station and hotel at Pittsburgh. His quarry and shaft kilns were located in Armour Gap between Bellefonte and Milesburg. (William Shortlidge’s younger brother, Joseph, who was not involved in the quarry industry, served as Penn State’s president from 1880-1881.)

In 1878, Tyrone entrepreneur Alexander G. Morris (1834-1924) bought out Shortlidge and began shipping lime to paper mills in Tyrone and Lock Haven. A few years later, Shortlidge joined McCalmont and Co. (in which his father-in-law was a partner) in a quarry and kiln operation near the confluence of Buffalo Run and Spring Creek. Quarrying limestone was difficult and dangerous, relying on men with picks, shovels, hand drills, black powder, and mule-drawn wagons.

Morris acquired the McCalmont property and in 1901 combined it with a dozen or so smaller quarries to form the American Lime and Stone Co. The company supplied limestone and lime to Bellefonte’s two large blast furnaces (Bellefonte and Nittany) and furnaces in nearby counties. However, steel makers began integrating blast furnaces with their mills and sourcing higher quality ore from the Lake Superior region. A blast furnace at a Pittsburgh mill might produce 1,000 tons of pig iron in a day—more than a small regional furnace could produce in a week—resulting in the closure of most smaller facilities. Bellefonte furnace went out of blast permanently in 1910; Nittany followed in 1911.

The steel industry’s growth stimulated demand for the county’s limestone and lime. In 1907 John S. Walker (Shortlidge’s son-in-law) and several associates formed the Chemical Lime Co. and secured land immediately west of the former McCalmont property. There they opened Plants 1 and 2 and shipped the output via the Bellefonte Central Railroad (BFC).

By 1920 the BFC was hauling as much as 280,000 tons of limestone and lime annually to its connection with the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) at Bellefonte for forwarding to steel mills and other industrial customers. While no PRR tonnage figures are available, that railroad almost surely originated even more product from American Lime and Stone. In addition, the PRR served a substantial quarry and kiln operation at Pleasant Gap, where William H. Noll and associates in 1905 established Whiterock Quarries. The Bellefonte area became the leading source of lime traffic on the entire PRR system.

American Lime and Stone, Chemical Lime, and Whiterock Quarries reigned as the “Big Three” Centre County producers, although two of the companies underwent a transition in ownership. Mechanization had come to quarrying in the early 1900s; even so, surface mining had practical limits. Going deep into the Bellefonte ledge required underground mining.

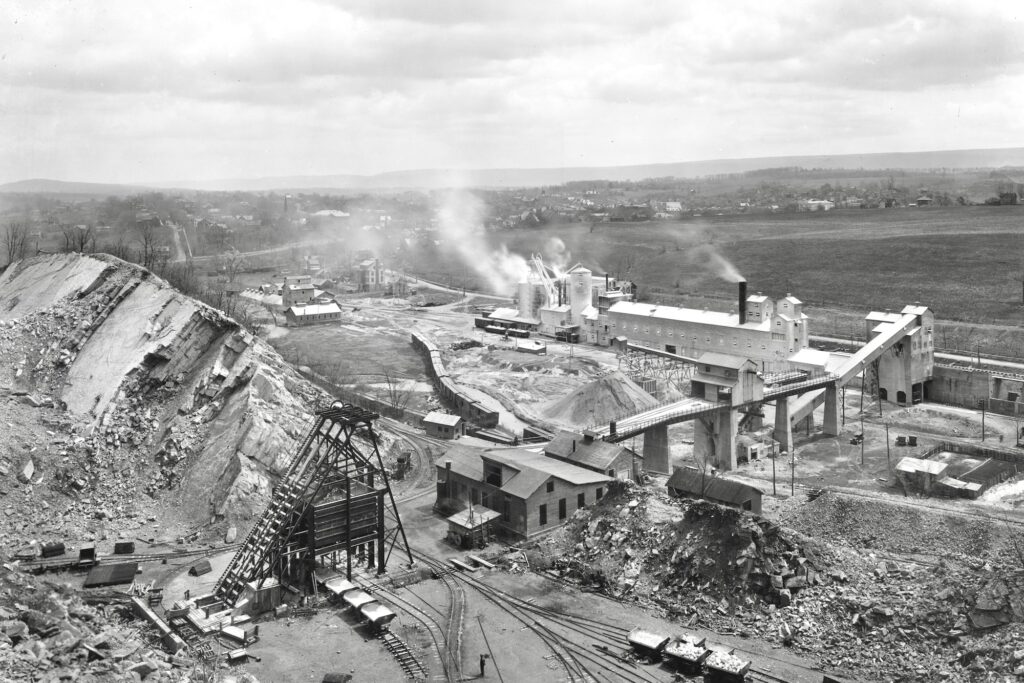

American in 1922 opened the Bell Mine, which eventually would reach a depth of nearly 1,000 feet and featured many levels of horizontal tunneling through the limestone vein. The mine fed a huge rotary kiln—the first in central Pennsylvania—that could produce 150 tons of lime daily. To obtain financing for the project, American’s owners sold control of their company to the Philadelphia-based Warner Company.

Chemical opened an underground mine of about equal proportions in 1937, installed an even larger rotary kiln, and went bankrupt. In a court-supervised reorganization, ownership passed to the National Gypsum Co. of Buffalo, New York. The new facility, officially labeled Plant 3, soon became known with considerable affection by locals as the “Gyp.”

As Warner and National Gypsum ramped up production on the eve of World War II, Whiterock Quarries began shutting down its obsolete shaft kilns and focusing exclusively on stone production. Its place among Centre County’s Big Three was taken by Baltimore-based Standard Lime and Stone. Standard’s test borings east of Pleasant Gap had revealed limestone of nearly the same purity as the Bellefonte ledge. The Pennsylvania Railroad constructed a 2.5-mile branch line to reach Standard’s underground mine and rotary kiln, which went into production in 1951.

By the mid-1950s, Standard, National Gypsum, and Warner combined were extracting more than 1.1 million tons of limestone annually and had a payroll of about 900 employees. Centre County led all other Pennsylvania counties by far in the production of lime (488,000 tons in 1954, a typical year).

The steel industry was the largest consumer of Centre County’s quarry products. However, the gradual elimination of open hearth furnaces beginning in the 1960s softened the demand for limestone. Steel imports also began cutting into domestic steel production.

In 1975 the National Gypsum operation was sold to the American subsidiary of Domtar, a Canadian firm. In 1982 a nationwide economic recession ravaged steel makers. Steel output that year totaled 69 million tons, compared with 138 million tons a decade earlier. Domtar closed the Gyp that year and sold it to Con-Lime, a local owner, which reopened the facility in 1983 on a reduced scale.

In 1986 Warner sold the Bell Mine and associated kilns to the Bellefonte Lime Co., established by a group of former Warner managers. They closed the mine a year later but continued making lime from alternate sources of limestone.

Standard’s underground mine and kiln operation—which also had undergone an ownership change—was acquired in 1998 by Graymont, a Canadian-headquartered firm that produced and marketed limestone and lime worldwide. Graymont bought Bellefonte Lime that same year and Con-Lime’s former Gyp operation in 2001, concentrating all mining and lime manufacturing at the Pleasant Gap site, where it invested $120 million in upgrades. Graymont supplied limestone and lime primarily to steel makers and pulp and paper manufacturers, and for such environmental purposes as water purification and acid rain reduction.

Even in the era of the Big Three, there had always been smaller quarrying sites in the county that sold limestone for construction and related uses and did not make lime. In recent years these included quarries near Oak Hall, Aaronsburg, Curtin Gap, and Pleasant Gap.

Michael Bezilla

Sources:

“Bellefonte Industries: American Lime and Stone,” Pennsylvania Historic Resource Series. Bellefonte Borough, 2006.

Bezilla, Michael, and Jack Rudnicki, Rails to Penn State: The Bellefonte Central. Harrisburg: Stackpole Books, 2007.

Miller, Benjamin L., Limestones of Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Department of Internal Affairs, 1934. Warner, Fred, “Centre County Limestone,” Centre County Heritage, April 1973, pp. 160-163.

First Published: August 27, 2023

Last Modified: February 26, 2024