The presence and impact of Native Americans in what is today Centre County is a matter of both history and popular imagination. In the millennia before European contact with indigenous Americans, archaeology provides the evidence on which to base an understanding of the culture and history of these peoples. From the sixteenth century onward, historical documents are relied upon.

Evidence indicates that the region between the West Branch of the Susquehanna and the Juniata rivers was primarily an area of hunting and transit for Native Americans with known Indian paths and trails following the terrain in what would become Centre County. These trails include the Logan Paths east and west, the Kishacoquillas Path and Karoondinha (Penn’s Creek) Path in the east, the Great Shamokin Path, Bald Eagle’s Path and Bald Eagle Creek Path in the north, and the Warrior’s Mark and Standing Stone paths in the southern part of the county. These intersecting paths formed a network as complex as today’s highway system.

The unfortunate fact, however, is that there is little or no historical documentation that reveals much about American Indian events in Central Pennsylvania in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Thus, most historical accounts of Native Americans in Pennsylvania begin with European encounters with them in the coastal regions in the 1600s, along with what European settlers learned about the interior Native Americans whom they traded with for furs.

As European settlers in Pennsylvania expanded inland from the Delaware River in the late 1600s and early 1700s, they took over native lands by purchase or simply by moving into “empty” land and assuming ownership of it. The population of native peoples who had occupied these lands had been decimated as waves of European infectious diseases, including smallpox, measles, influenza, and bubonic plague, spread throughout the hemisphere.

Some bands or “tribes,” like the Mahicans, Conoy, Nanticokes, and remnants of other Algonquian-speaking communities that lived in or near the Delaware River Valley, and especially the Lenape, whom the English called collectively “Delawares,” began to move west to the Susquehanna River Valley in the early 1700s. Some from the south came to the lower Susquehanna area.

As early as 1700, groups of another Algonquian-speaking tribe, the Shawnee, had migrated into Pennsylvania from the south and west, moving into the Susquehanna and Allegheny River valleys. In the 1730s and 1740s, there were Shawnee settlements at Great Island (present-day Lock Haven) on the West Branch, and there was a Shawnee town at Ohesson on the Juniata (present-day Lewistown) under a chief named Kishacoquillas. These groups however moved west as the conflict for empire between the French and the British grew in the 1750s.

Indian villages could often be nearly eradicated by such diseases spread from other native peoples without ever seeing a European. Scientists believe approximately 90% of the Native American population died from disease and its consequences, leaving by 1800, only about one million Indians in all North America.

Other Delaware refugees had moved inland to the area of today’s Reading and Berks County in the 1720s, but then on to the growing Indian settlement of Shamokin at the junction of the North and West branches of the Susquehanna, near today’s Sunbury by 1742. There the Iroquois had installed a Cayuga chief Shikellamy, as overseer of their southern borderlands in the area as early as 1728. His son John, better known as “Chief Logan,” took over his responsibilities at his death in 1747.

Shamokin was one of the key settlements in the Iroquois effort to protect the Confederation’s lands in upstate New York. They controlled the fur trade with both New York and Pennsylvania traders by maintaining a buffer of open “Indian” land across northern Pennsylvania from the Wyoming Valley to Kittanning on Allegheny River on the edge of the Ohio Country.

Connecticut settlers, organized by their Susquehanna land company, began their intrusions into the Wyoming Valley in the early 1760s. Conflicts with Delaware and Shawnees there led to the First Wyoming Valley massacre of these settlers. Fearing reprisals, some of these Native American groups fled the valley to settle along the West Branch near present-day Lock Haven, while others continued west to the Allegheny River Valley, as other members of these tribes had done.

The initiation of war in 1754 in Western Pennsylvania was the unintended consequence of the English desire on the part of Pennsylvanians, Marylanders, and Virginians to expand their settlements into Western Pennsylvania and beyond the Ohio River. Much of the action took place along the road and pathways stretching from Carlisle in Cumberland County — the western extension of Pennsylvania settlement from Philadelphia to Harrisburg and on across the Susquehanna — to the occupation of Fort Duquesne and the development of English control over the forks of the Ohio.

Pioneer settlements spread along the waterways, including up the Juniata, in the 1750s and early 1760s. They became subject to Indian and French raids on settler farms and small settlements in the early years of the war. People in these frontier areas were killed in these raids, while others fled back east and south to the line of British forts stretching from Fort Augusta near Shamokin southward to Carlisle and Bedford.

The peace treaty between the British and the French, signed in Paris in 1763, ceded New France to Britain, giving them legal title to the Ohio and Illinois countries as well as to Canada. A line of demarcation along the Allegheny summit (an indefinite and unsurveyed line which could well have been the Allegheny Front) was supposed to be the limit of colonial settlement with the lands beyond, all the way to the Mississippi, reserved for the Indians, although dotted with British military outposts.

The Pennsylvania government wanted to establish peaceful relations with the Indians through diplomacy, gift-giving, and trade. Since trade/diplomatic gifts included powder, ammunition, and knives, the frontiersmen “rebelled” against the traders to prevent these goods from finding their way to the Indians. Some settlers attacked peaceful Indians, which raised Native American suspicions at the very least that there could be no peaceful relations with the settlers.

Within this larger context, the proprietary government made treaties with the Indians in the late 1750s and 1760s to open more land west of the Susquehanna, but, theoretically, east of the indefinite demarcation line, for settlement. In separate land agreements executed at Albany, New York on July 6, 1754, the Iroquois bargained away a vast swath of south-central Pennsylvania, including a substantial portion of what would become Centre County. By signing the 1754 Albany Purchase and the later 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, which covered the rest of the county-to-be, the Iroquois had sold all Centre County land, and any claims the Delaware or the Shawnee may have had, to the colonial government.

Captain James Potter, one of the surveyors for the proprietary land office, made his famous 1764 roundtrip journey from Fort Augusta at Shamokin up the West Branch, the Bald Eagle, and then Spring Creek, across the Nittany Valley and the Nittany Ridge, to view Penns Valley. He descended into and crossed the valley, and followed Penn’s Creek to the Susquehanna, from where he journeyed back to Fort Augusta. He then endeavored to get to Philadelphia and take out warrants for Penns Valley. He was in competition with Reuben Haines for the title to these lands, and they eventually split the valley.

The purchases of the this land and the expansion of government through the creation of counties — Cumberland, then Northumberland, Bedford, Huntingdon, Mifflin, and eventually Centre (this stretches from the 1760s, through the Revolution when Indian-white conflicts in 1777 and 1778 again drove Potter’s frontier settlers back east in the “Great Runaways,” and into the development of the state government, 1783 to 1800) — created conflicts as well because the understanding of the geography was indefinite. As a result, county lines conflicted and caused problems for warranting and patenting lands.

By this time, and in 1769 when Andrew Boggs, the county’s first settler, arrived on the Bald Eagle Creek near today’s Milesburg, Native Americans had, for the most part, departed what is today Centre County for good. However, “for the most part,” obscures the persistence of native individuals who intermarried with European settlers, or small groups like a community of peaceful Seneca, part of the “Cornplanter Indians” who lived in the Upper Bald Eagle Valley and near Philipsburg for a time in the early nineteenth century, before being granted land near Warren, Pennsylvania, which they continued to occupy until the Kinzua Dam controversy in 1967.

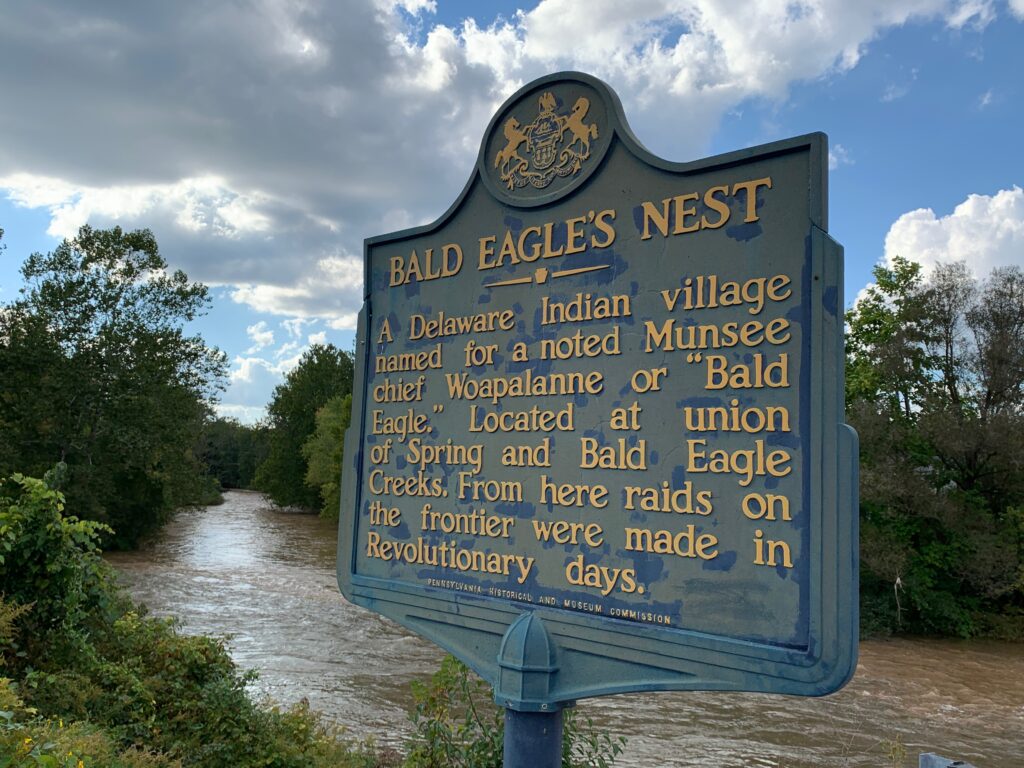

The other aspect of the persistence of Native Americans is represented in several ways. One is the continued use of Native American place names in the county. Nittany Mountain and valley were supposedly named for the mysterious Princess Nita-Nee. Black Moshannon Lake in Black Moshannon State Park takes its name from the Native American word, Mos’hanna’unk, which means “elk river place.” Bald Eagle State Park, as well as Bald Eagle Creek, valley, and ridge re named for for the Delaware (Munsee) Chief Bald Eagle, whose village was located at one time on an island at the junction of Spring and Bald Eagle Creeks. He is also referred to at times as Woapalanne, (as is Waupelani Drive in State College). Then there is the village of Mingoville (Mingo being a Delaware name for Iroquois from the west or likely Senecas); and the Logan Branch of Spring Creek and Bellefonte’s Logan Fire Company from Chief Logan, the son of the Cayuga chief Shikellamy, among others.

Perhaps more notable has been the evolution of attitudes on the part of eighteenth-century frontier settlers who saw American Indians as “bloody savages,” who they would rather kill on sight than coexist with, to a romanticized, “noble savage” of the turn of the twentieth century. In the twentieth century, American Indians became objectified, stock characters in fiction, films, and television. First, they were the obstacles to the inevitable progress of white settlers’ “manifest destiny” to civilize this continental wilderness, but eventually, they became honored reminders of the natural environment we had very nearly destroyed through America’s own greed and thoughtlessness.

Today, there are still Native Americans living in Centre County. Their identity as American Indians is diverse, and they represent many nations. There is no reservation, no recognized native tribe in Pennsylvania, but Native Americans live and work in the county, preserving as much of their cultures and identities as they are able.

Beginning in 2004, dancers and drum groups from across North America have participated in the annual “New Faces of an Ancient People Traditional American Indian Powwow.” The two-day event, founded by Professor John Sanchez (Ndeh Apache), celebrates American Indian culture and spirituality with inter-tribal dancing, songs, and foods, as well as Native American vendors showcasing and selling their art and crafts. It is sponsored by several Penn State units, including the Donald P. Bellasario College of Communications and the Office of Student Affairs.

Another type of engagement with the Native American community was the Penn State College of Education’s American Indian Leadership Program, which operated for more than thirty-five years beginning in 1970. It provided graduate education to more than 200 educators from Indian Nations across the country. Most would go on to serve in administrative and policy-making positions in tribal organizations, federal and public schools, and federal and state governments.

Ralph Seeley & Lee Stout

Sources:

Koch, Alexander, Chris Brierly, Mark M. Maslin and Simon L. Lewis. “Earth System Impacts of the European Arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492,” Quarternary Science Reviews. Vol. 207 (March 1, 2019), 13-36.

Linn, John Blair. History of Centre and Clinton Counties, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, Louis H. Everts, 1883.

Minderhout, David J., ed. Native Americans in the Susquehanna River Valley, Past and Present. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2013.

Richter, Daniel K. Native Americans’ Pennsylvania. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania Historical Association, 2005.

Schutt, Amy C. Peoples of the River Valleys: The Odyssey of the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

Seeley, Ralph. Indian People and Their Paths. State College, PA: Centre County Historical Society, 2018.

Wallace, Paul A.W. Indians in Pennsylvania. Rev. Ed. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1989.

First Published: September 27, 2021

Last Modified: December 2, 2025