Centre County’s agricultural history is geographically bifurcated. The Allegheny Front divides Pennsylvania’s fertile Ridge and Valley region from the agriculturally less well-endowed Allegheny Plateau. On the plateau, diversified small-scale farming and industrial work intermingled, while in the valleys, there was a more thoroughly agricultural economy.

Before about 1830 the county’s small farming population settled mainly in the valleys. As land was cleared, diverse farm production sufficed to provide food for animals and residents. Most farmers kept livestock, but care was rudimentary; swine, for example, ran free most of the year. Finding markets was a problem because transportation was poor, so farm families sent out goods that had a high value in proportion to their bulk: whiskey, clover and flax seed, maple sugar, and wheat.

By the mid-nineteenth century, agriculture in the limestone valleys was well established. Over time the agricultural population had become more Pennsylvania German. Farm size averaged about 100 to 120 acres.

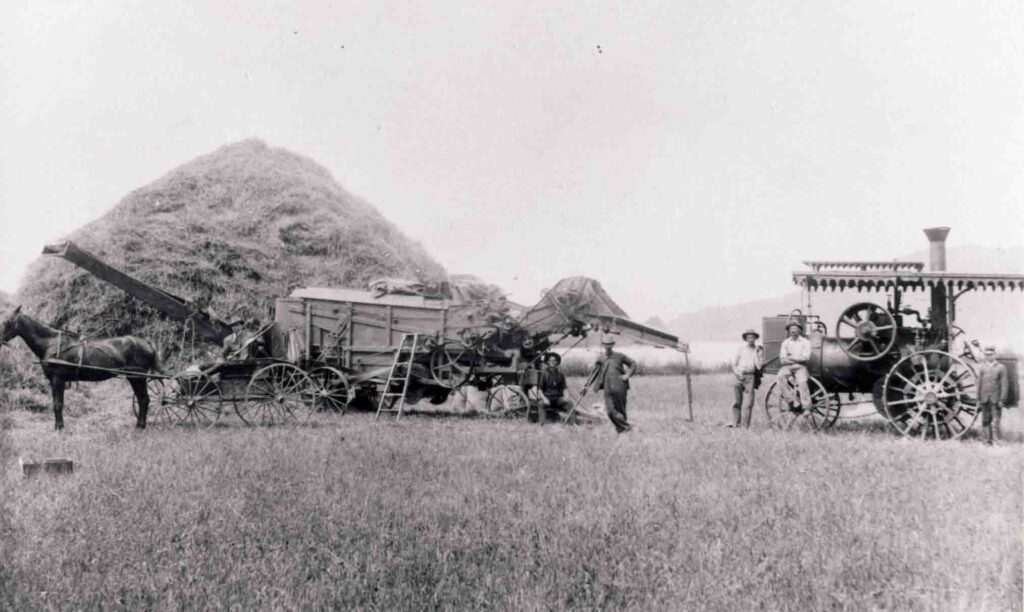

Transportation had improved, but the county was just distant enough from urban centers to push production toward easily moved goods such as cash crops and livestock. The major agricultural shift in this period was toward a highly mechanized, integrated grain and livestock economy. Land-use strategies allotted a central place for cropland, but meadow (for hay) and pasture (for grazing) were also important to provide winter feed and summer grazing.

The valleys’ limestone soils and flat topography lent themselves well to corn, wheat, oat, and rye production. Grain was both marketed for cash and fed to animals. Oats fueled the farm’s source of motive power, the horse. Corn fattened swine and beef animals, which were then driven to market.

Grains, hay, and pasture were rotated and manured systematically in a cycle that sustained productivity. Wood for sale, fuel, fencing, and lumber was obtained from mountainside lots. Poultry were found on every farm. Dairying output was modest, but every farm had a few milk cows and sometimes produced small butter surpluses for market.

Diversified orchard and garden production added an important layer to farm household strategies. Farm people raised, processed, and stored most of their food supply. Few farm households achieved self-sufficiency on their own, but by swapping labor, skills, goods, and cash with neighbors and kin, they could make up deficits.

Summer kitchens, smoke houses, ice houses, spring houses, root cellars, and dry houses provided spaces for processing and storing popular food items. In their summer kitchens, Pennsylvania German women prepared ethnic specialties such as scrapple, as well as a range of canned and preserved goods.

Farming in the valleys was often conducted within a distinctive land-tenure system. A holdover from Old World customs, kinship-based share tenancy functioned as a kind of old-age insurance. A patriarch would lease farmland, usually for a year, to a son or other male relative, and the tenant would pay a share of the crop as rent. If the owner died, his widow could collect the rent for her support. This system created an interesting generational dynamic. The patriarch and his wife would retire to town, often Centre Hall, while the young people struggled to achieve landownership.

There was continual turnover. “Flitting” day usually occurred on March 1 or April 1. The local newspapers chronicled this “Annual Crisis” by describing households relocating with wagons piled high, noting in gossipy asides which family would take up which farm. Tenancy even helped raise the already high level of farm mechanization, since renters often owned their equipment.

The famous Pennsylvania forebay bank barn dominated the valley landscape, and no wonder, since it beautifully accommodated an integrated grain and livestock system. On the upper-level hay were hay mows, threshing floors, and granaries, the last frequently in the overhang or “forebay.” In the stables below, the cattle and horses were sheltered. Their manure accumulated in the stable and yard area.

Over time the barn’s design easily accommodated mechanization. Newer barns were built with integral machinery bays, or with a large ell to accommodate the huge mounds of straw that appeared when steam-powered threshing came along. The barn type also accommodated share tenancy; hay mows, granary bins and even livestock quarters were commonly designated for tenant and landlord respectively.

Meanwhile across the Allegheny Front, the texture of farming was shaped by poor soils and wrinkly, hilly terrain. Allegheny Plateau farms were less developed and relatively unproductive. Another contrast was demographic; the plateau population included migrants from other states as well as from Europe.

The watchword was diversification: a typical farm in this part of the county would have just a few animals and produce small crops, all with minimal equipment. Even so, barns and outbuildings could be substantial because so much of the farm’s needs were produced, processed, and stored on-site.

Allegheny Plateau farming households depended heavily on industry. In the iron township of Boggs, almost thirty percent of the farmers listed in the tax records of the 1850s rented land from iron furnace owners like the Curtins. Tenants usually received a share of the crop, but sometimes they were paid in kind with iron products. These farms supplied the plantation workforce — both animal and human — with foodstuffs.

Later, farm men found wage work in lumbering and bituminous coal mining while the women and children did much of the farm labor. Wage work and farm work combined allowed for greater household economic security than one or the other alone.

In the early 1900s the number of farms and farm acreage in the county peaked at about 2,600, then began a sustained decline. Average farm size increased modestly. The farms that remained were on better-resourced lands primarily in the valleys. These farms contended with an ever more competitive environment.

Geographic, economic, and political factors on a national scale put Pennsylvania’s small farms at a disadvantage. Penn State’s land-grant agricultural research and extension programs sought to improve farms’ position, as did government programs with goals like conservation or price support. However, even these well-intentioned efforts did not always mitigate the problems they were designed to address.

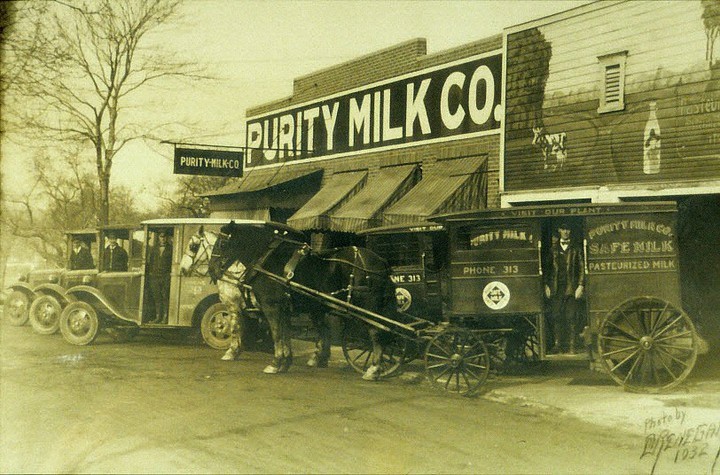

Greater agricultural specialization took hold. For example, as road and rail transportation improved, Centre County was drawn into the orbit of the New York City “milkshed.” Farm production shifted to dairying. Cash grains (like wheat) were de-emphasized in favor of feed crops such as alfalfa, silage corn, field corn, and hay. Meanwhile, as the tractor replaced the horse, oats acreage declined. Rates of tenancy continued high, though sometimes leases had to be modified in the era of the regular milk check.

Creameries in Bellefonte, State College, Spring Mills, and Howard were in operation by 1930. They made butter and shipped milk to New York City. In the 1930s, a “milk depot” in Centre Hall collected from more than 100 farms.

Another important rising specialty was poultry. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Kerlin Hatchery in Centre Hall shipped millions of chicks all over the nation. This had an impact on local farming, as the hatcheries encourage local farm families to supply them with eggs. The silo, milking parlor, and poultry housing were evidence of these new trends.

Although they adapted with considerable resourcefulness, the county’s farming families still had to contend with an ever-worsening competitive environment. This was especially evident after the World War II.

A cost-price squeeze put pressure on farming: expenses for “inputs” (equipment, fertilizer, fuel, pesticides) consistently exceeded income from farm products. Consequently off-farm work (often by women) became critical even for valley farms. By 1970, the number of farms in the county had dipped to just over 700.

In the late twentieth century, the rate of farm loss seemed to slow. It is not clear whether this was an actual trend, since the definition of “farm” had changed significantly. It is clear, However, that farm production became more specialized and more concentrated.

A trend that had a positive effect on the county’s agricultural prospects was the arrival of Amish and other Plain Sect families beginning in the late twentieth century. Their communities in the Brush, Nittany, and Penns valleys have grown steadily and have had a significant impact by keeping the fertile land in agricultural use.

A county farmland preservation program, a small but vibrant local farming scene, and a continually adapting conventional farm sector offer reason to hope that agriculture will continue to be a vital part of Centre County’s economy.

Sally McMurry

Sources:

“Agriculture in the Settlement Period to about 1840.” “Allegheny Mountain Part-Time and General Farming.” “Central Valleys.” Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania Agricultural History project. http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/agriculture/history/index.html (Accessed August 15, 2021).

Democratic Watchman, April 4, 1861.

McMurry, Sally. Pennsylvania Farming: A History in Landscapes. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017.

McMurry, Sally. “The Pennsylvania Barn as a Collective Resource.” Buildings and Landscapes 16:1 (Spring 2009): 9-29.

USDA Census of Agricultural Historical Archive. http://agcensus.mannlib.cornell.edu/AgCensus/homepage.do;jsessionid=A82154AEA1967117A455DB1DBE00343A (Accessed August 15, 2021).

First Published: May 19, 2021

Last Modified: March 5, 2025