October 1864 likely was an anxious month for Centre County’s Black community. By then residents would have learned that six of their soldiers had suffered wounds on September 29 at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm in Virginia. A Union attack had failed, but the 6th U.S. Colored Infantry, in which the soldiers fought, acquitted itself well. So did others: overall, the battle resulted in awarding the Medal of Honor to fourteen African Americans.

Centre County’s soldiers survived the battle, but their experiences—combined with other African Americans in what was called the U.S. Colored Troops—provide insight into the recruitment of the North’s Free Blacks into the army during the Civil War.

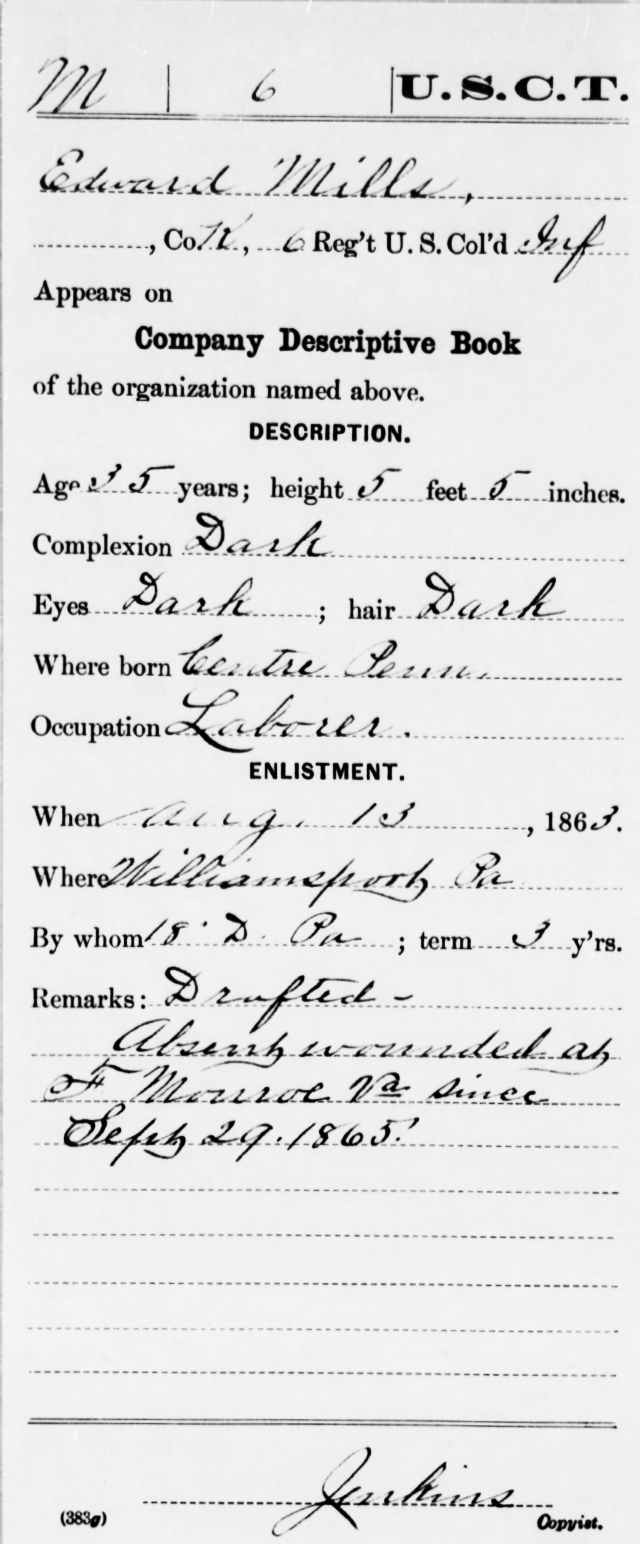

Most local Black soldiers had to be either compelled by the draft or enticed through economic incentives. Service records reveal that, just like white men, Black men were drafted—a detail that has been missing from scholarship on the war. Of twenty-eight Black males with Centre County connections, twelve were conscripted. Five others served as substitutes, meaning that each accepted money from a draft-eligible person to serve in his place.

Black men needed incentives to volunteer, and for valid reasons. They were assigned to segregated units led by white men. Until late in the war, they were ineligible to become officers. They were unsure that they would even fight rather than being assigned to hard labor. They received unequal pay: $84 a year instead of $156 for white soldiers (a considerable cut from the $180 that most farm hands earned). Finally, the Confederate president had proclaimed that the Rebel government would not consider Black soldiers who were captured as prisoners of war but as men to enslave.

Despite these circumstances, the number of men serving from the county was impressive. The 1860 census counted fifty-one Black men of approximate military age. The twenty-eight who became soldiers constituted 55 percent of that cohort.

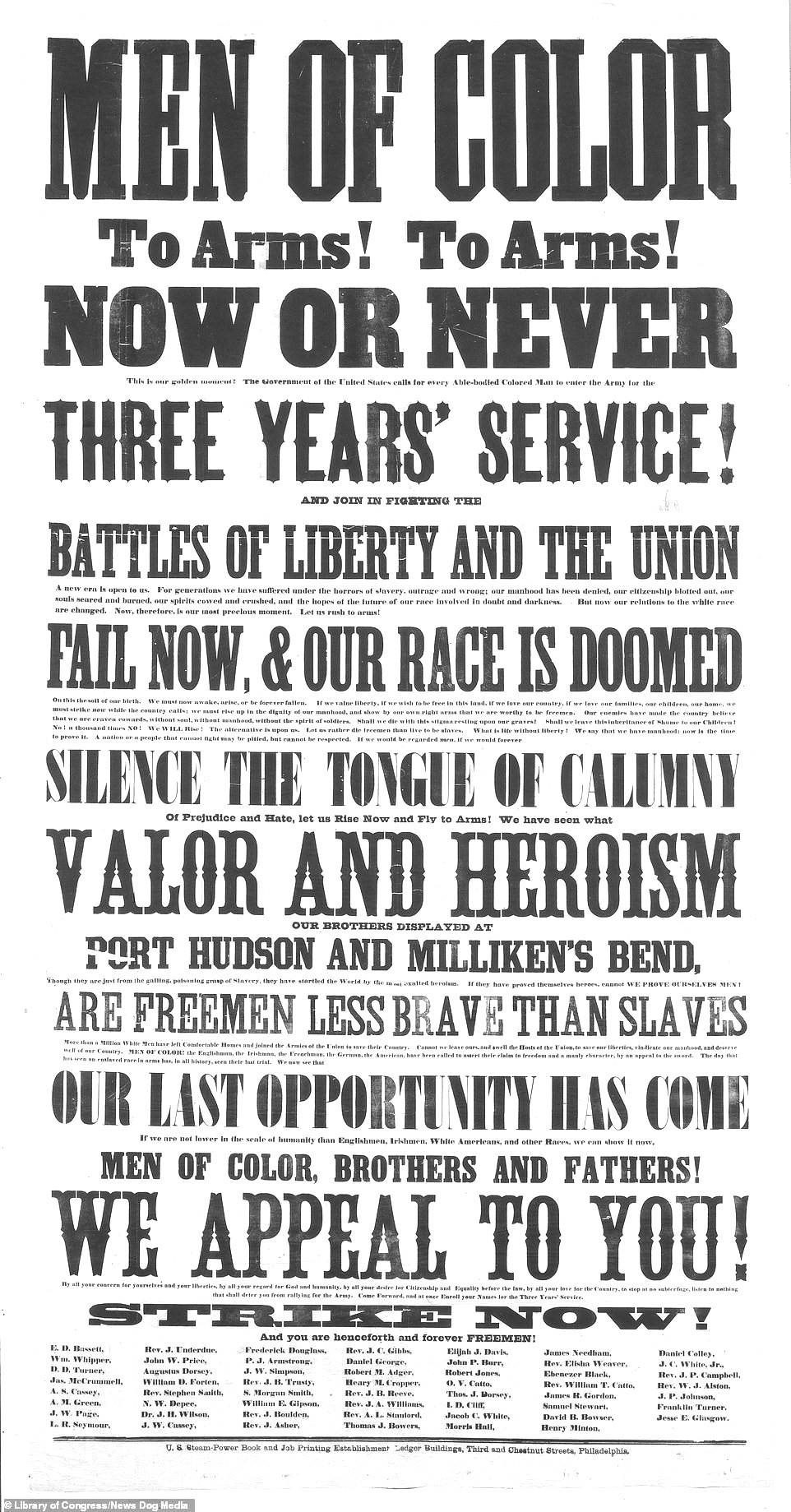

The journey that led to six soldiers sustaining wounds in the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm began in earnest in the summer of 1863. Before then, overtures by African Americans to serve in the war had largely been rebuffed by the government. Legislation in July 1862 had allowed for recruitment of African Americans, but politics delayed their mass involvement until after President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863.

Twenty-two local soldiers went into the ranks in late August 1863, ten as draftees. The majority were mustered in at Williamsport and then transported to Camp William Penn at Cheltenham, near Philadelphia. That camp processed roughly 11,000 men, or about a third of the Free Blacks from the North who entered the military. Most became part of the 6th US Colored Infantry.

One person enlisted earlier than most. In May 1863, Isaiah H. Welch rushed to join the 54th Massachusetts, the unit lionized in the movie “Glory.” Because so many men responded, he was transferred into a sister unit, the 55th Massachusetts, where he served as a sergeant. Welch had lived in Bellefonte before the war and had been a servant for future Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin.

As a group, Centre County’s Black troops were not from the upper classes. Four identified themselves as farmers and the rest were laborers. Their ages ranged from 17 to 39, with an average age of 27.4, a little older than the 25.8 average for white men. Two died in action, six were wounded, and several died from disease. Eleven of the twenty-eight served as noncommissioned officers—soldiers holding the rank of corporal or sergeant.

Two of the best-known recruits were Lewis and Edward Mills, ancestors of the men who formed The Mills Brothers quartet that sang on national radio beginning in the 1930s. Lewis and Edward Mills were the sons of fugitive slaves who had settled in Pennsylvania. Lewis, the elder by four years, became the father of William Hutchinson Mills, a barber in Bellefonte who trimmed the hair of Frederick Douglass when Douglass visited in 1872. William’s son sired the boys who became the popular singers.

Lewis and Edward Mills crossed the James River on September 29, 1864, at Deep Bottom Landing. The 6th U.S. Colored Infantry was part of a two-pronged advance by soldiers in the Army of the James against Rebel defenses near Richmond. The brothers were among the 5,000 casualties. Lewis returned to the ranks in January 1865, but Edward remained absent from active duty until the summer.

Four more local soldiers sustained wounds in this engagement. Hartshorn Patterson, also of the 6th USCI, received a gunshot wound in the right foot that apparently did not heal. He received a disability discharge on May 20, 1865. Sergeant Aaron Worley also was wounded; the type of wound he suffered was not part of the record, but it kept him from returning to the ranks until July 1, 1865.

Meanwhile, Sergeant Daniel W. Smith experienced the fate of many a color bearer—soldiers who marked the center of the line by carrying a flag. This role was considered an honor borne by someone brave, since color bearers were often the first targets of enemy fire. While at Deep Bottom, Smith was hit in the right shoulder, costing him a partial loss of motion in his arm and hand. He received a disability discharge in August 1865.

Sergeant Charles Garner, also wounded, had a unique aspect to his service that has not made it into the histories of the war. Garner, a 19-year-old laborer, was hired by a Black man in Lock Haven to serve in his place. Garner was struck in the left thigh by a minie ball, returning to duty in February 1865.

In other action, two county soldiers died while performing their duties. One of them, Moses Johnson, a 22-year-old Bellefonte farmer, enlisted on August 26, 1863. A member of Company F of the 6th USCI, he drowned in the James River on August 28, 1864, while building a canal to circumvent Confederate artillery.

The death of William Derry, a 23-year-old laborer from Bellefonte who enlisted on August 23, 1863, resulted in a pension for his widow, Matilda. Her case illustrates the process of government pensions for survivors of soldiers killed in the war.

Matilda was 24 years old when William was killed on June 28, 1864, by an artillery in the rifle pits before Petersburg, Virginia. Three months later, Matilda filed for a pension. She quickly netted the $8-a-month widow benefit, which dated from the time of William’s death. Later, she received an additional $2 per month for her daughter, Mary Letitia Carter, after Congress in 1866 authorized this compensation for every child under 16 of a soldier-father who died.

Matilda’s pension lapsed when she remarried, but in 1917, after her second husband died, Matilda filed again. After hearing from witnesses in the Centre County Courthouse, the special examiner supported her claim, saying she enjoyed good standing in the community. She had been a servant with Daniel Hastings, both in his Bellefonte home and when he went to Harrisburg to serve as the Pennsylvania governor. Matilda received $20 per month, which increased to $50 by the time of her death in 1932.

Not all the stories of Centre County Black soldiers turned out positively. Alexander Delige, a 39-year-old laborer who landed in Company I of the 32nd USCI, deserted twice. Both times the provost marshal caught him in Centre County. As was often the case, he did not face execution but had his pay docked and was returned to the ranks.

Two other county residents deserted, and both returned to duty. Black desertion was no worse than that of white troops, even though African Americans had greater reasons for doing so. They could face white officers of questionable ability who showed their prejudice against Black men. And they chafed at the inequities between them and white soldiers. All told, an estimated 12,400 Black men deserted out of roughly 200,000.

At least seven men included in this article are not listed on the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial in Bellefonte. Several on that monument could not be found in the service records. What exists here are the soldiers for whom records validated their army experience. Future research may well turn up more names.

William Blair

Sources:

Bates, Samuel Penniman. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 volume 4. Harrisburg: R. Singerly, State Printer, 1870.

Berlin, Ira, et. al., eds. Freedom: a Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867. Series II, The Black Military Experience. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Civil War Service Records (CMSR)-Union-Colored Troops, Compiled Service records of the National Archives, available on Fold3.com.

Linn, John Blair. History of Centre and Clinton Counties, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1883.

Pinheiro, Holly A., Jr. The Families’ Civil War: Black Soldiers and the Fight for Racial Justice. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2022.

Taylor, Brian. Fighting for Citizenship: Black Northerners and the Debate over Military Service in the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

United States Colored Troops, Camp William Penn Headquarters, Database and Archive, https://www.usct.org/database-archive/ (Accessed March 6, 2023).

First Published: March 27, 2024

Last Modified: May 27, 2024