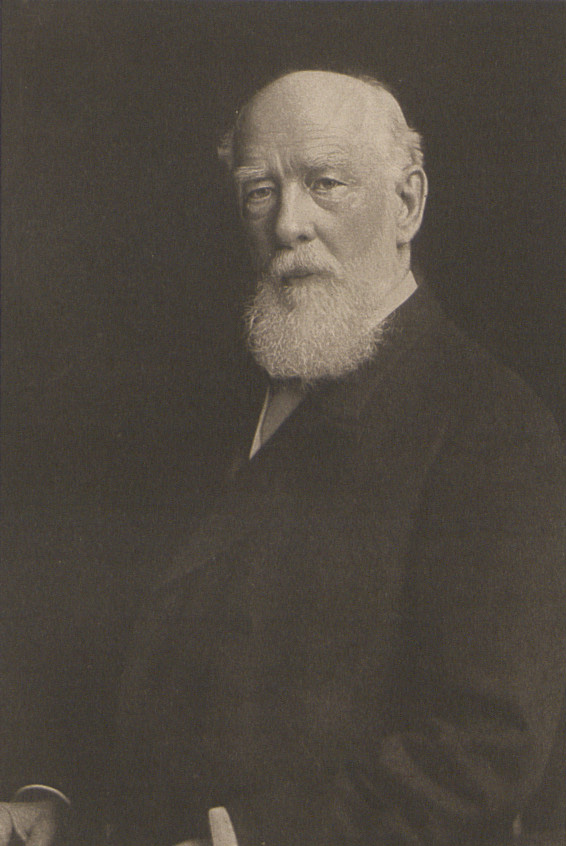

George Washington Atherton — Penn State’s “second founder” — was the longest-serving president in the institution’s history. During nearly a quarter-century, from 1882 to 1906, Atherton took a failing college and transformed it into a stable institution poised for growth in the twentieth century. For all his work in building Penn State, however, perhaps his greater achievement was his national leadership in the land-grant college movement.

Founded as the Farmers’ High School of Pennsylvania in 1855, the institution under the leadership of Evan Pugh quickly became the most successful agricultural college in America emphasizing science. It was designated as Pennsylvania’s land-grant institution under the 1862 Morrill Act, in which agriculture and engineering were to be the “leading object.”

After Pugh’s death in 1864, however, the school — renamed in 1862 as the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania — went into an eighteen-year decline under five unsuccessful presidents. By the late 1870s, it had devolved into a backwoods classical or “literary” college, abandoning its original emphasis on agricultural science and never developing an engineering program.

In 1881-82, a faculty committee revamped the curriculum of the failing school, reconciling it to its land-grant mission. Still, enrollment continued to decline, and in 1882-83 there were only twenty-three students. Led by Trustees President James A. Beaver, the governing board of the Pennsylvania State College (renamed in 1874) embarked on a careful search to find a leader who understood what land-grant colleges needed to be.

In the summer of 1882 they found him in Atherton, then 45 years old and the Vorhees Professor of History, Political Economy, and Constitutional Economy at Rutgers College. Accepting the offer, Atherton wrote to Beaver: “I understand full well that my path is not to be strewn with roses.”

Atherton was born in Boxford, Massachusetts, in 1837, of old Puritan stock. His father died when he was 12, and young Atherton became the main support for his mother and sisters. He managed to gain an education sufficient for teaching and tutoring, and in 1855, at 18, he got his first teaching job. In 1856 he enrolled in Phillips Exeter Academy, graduating in 1858. He enrolled in the sophomore class at Yale in 1860.

During the Civil War, he left to join the Union Army as a first lieutenant in the Tenth Connecticut Volunteers. He saw action in the Carolinas and, after suffering a near-fatal illness of the swamp-fever type, he resigned his commission and returned to Yale in June 1863. He graduated in 1864 and four years later joined the faculty of the new Illinois Industrial University (now the University of Illinois). In 1869 he moved to Rutgers, where he stayed for thirteen years.

At Rutgers, Atherton emerged as a champion of land-grant colleges. At the 1873 National Education Association convention in Elmira, N.Y., he garnered national attention for his defense of land-grant colleges against criticism from the presidents of Harvard and Princeton. That same year, he began working with U.S. Senator Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont in drafting bills to bring further federal support to the land-grant institutions, bills that would culminate in the “second” Morrill Act of 1890. He also led the colleges’ successful defense against the Congressional investigation of 1874.

Arriving in Centre County in 1882, Atherton embarked on the “rehabilitation” of the college. Shortly after his arrival, Atherton rebuffed an effort of Governor Robert Pattison to cut the school’s faculty in half. He also focused on the long-neglected engineering disciplines. “The institution aims to hold the highest rank as a school of technology,” he told the trustees. He secured the college’s first state appropriation in a decade — $100,000 in 1887, which helped to establish an agricultural experiment station — and appropriations in 1889 and 1891 totaling $277,000.

The crowning glory was the college’s new engineering building, dedicated in 1893 on what is now the site of the Sackett Building. By 1893-94, 128 of the college’s 181 undergraduates, or 71 percent, were enrolled in engineering. In 1895, Atherton reorganized the college, melding the liberal arts with science and technology through seven new schools: Agriculture; Engineering; History, Political Science and Philosophy; Language and Literature; Mathematics and Physics; Mines; and Natural Science.

Student life blossomed through the introduction of intercollegiate athletics, fraternities, and publications. With private gifts, he built Schwab Auditorium and Carnegie Library. Despite reduced state funding in the latter part of his tenure, undergraduate enrollment grew to 680 by 1905.

Atherton continued his leadership on the national level. He drafted the 1887 Hatch Act, providing annual federal appropriations for agricultural experiment stations at every land-grant college. He led the intense lobbying to pass the second Morrill Act of 1890, which generated annual federal appropriations for the colleges’ academic programs from English to engineering.

Atherton was elected the founding president of the new Association for American Agricultural Colleges and Experiment Stations, the first formal higher education association in America. He served two terms, from 1887 to 1889.

Atherton died in 1906 while still serving as president, and he was buried next to Schwab Auditorium. Atherton Street in State College is named for him.

For Atherton’s work modernizing the school that would become Penn State, Dean Benjamin Gill eulogized him: “He came to this bunch of houses with as much pride as if he were assuming the presidency of Cambridge or of his alma mater, Yale, because he saw from the first not the college that was, but the college that was to be.”

Roger Williams

Sources:

Bezilla, Michael. Penn State: An Illustrated History. University Park: Penn State University Press, 1985.

Williams, Roger L. The Origins of Federal Support for Higher Education: George W. Atherton and the Land-Grant College Movement. University Park: Penn State University Press, 1991.

First Published: May 20, 2021

Last Modified: March 10, 2023