The manufacture of refractories – brick capable of withstanding temperatures as high as 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit – was one of Centre County’s major industries for more than seventy years. By the early 20th century, about 800 workers at eight brickyards across the county were producing what was commonly known as fire brick. The product was used to line furnaces in mills making steel, glass and lime, in residential houses, and in steam locomotives. Today, with declining demand for their product, the county’s brickyard jobs have largely vanished.

As the nation industrialized in the second half of the 19th century, the production of refractories flourished in Centre County because of the abundant deposits of flint clay on the high ground of the Allegheny Plateau in the county’s northwestern quarter. Flint clay, characterized by a high concentration of aluminum oxide, was ideal for making refractories.

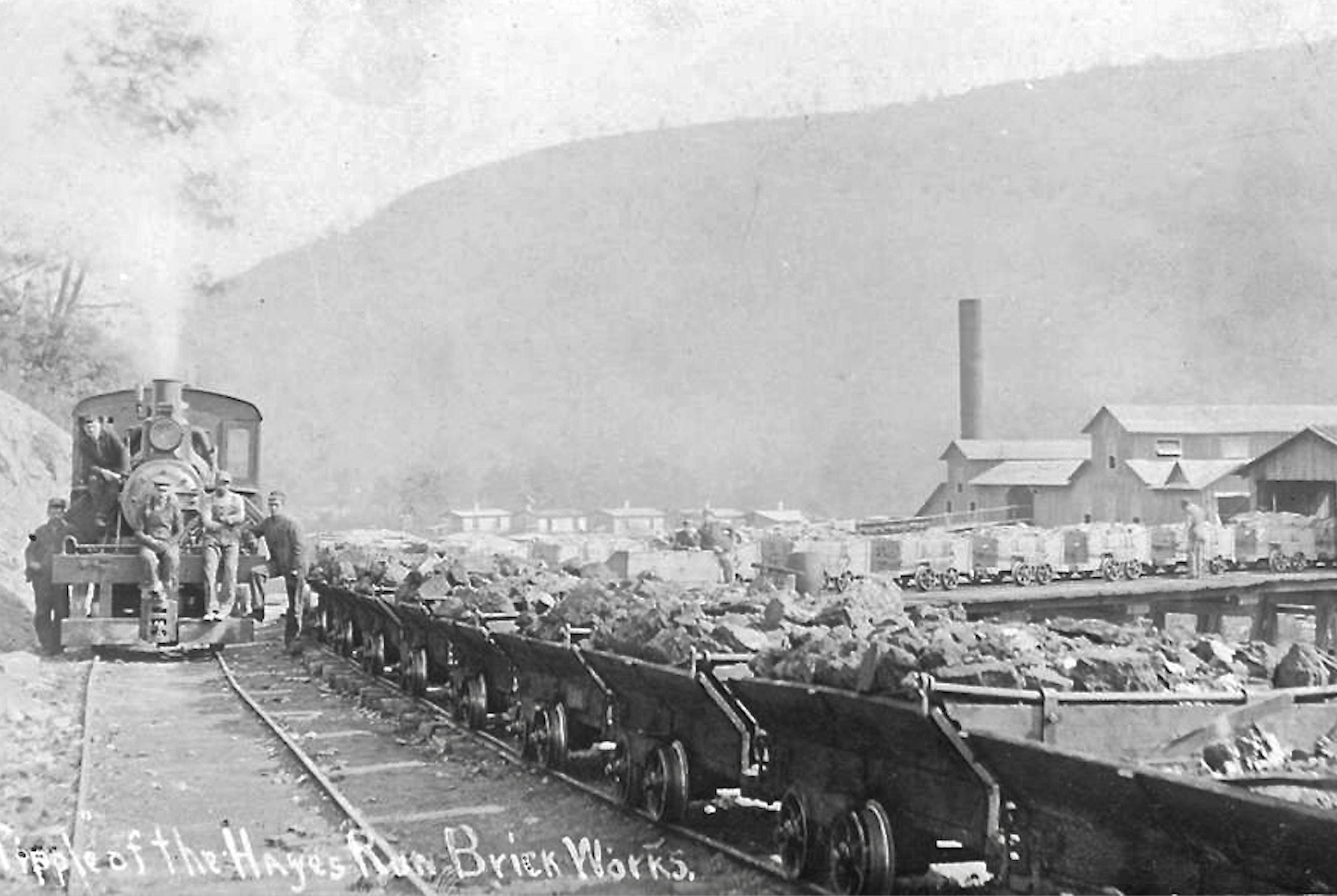

Flint clay was so hard that, to be molded into brick, it had to be mixed with softer clay also found on the plateau. Clay was obtained from underground and shallow surface mines and usually transported to nearby brickyards on narrow-gauge railroads.

At the brickyard, the clay was crushed, mixed with water, and pressed into molds by hand. These “green” bricks were set aside to dry. Then they were heated for a week or more in coal-fired shafts or beehive-shaped kilns. When they had cooled off, the bricks were shipped in railroad boxcars. The process was labor intensive and relied on workers who got no formal training but learned their skills through years on the job.

Making fire brick began in 1866 at Sandy Ridge. John Miller & Son established a brickyard adjacent to the Clearfield Branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and soon it was producing 25,000 brick a day and shipping them to customers in seven states. Soon the Millers were producing 25,000 brick a day and shipping their output to customers in seven states. In 1881 the company erected twenty frame houses to rent to employees. By then John Miller had retired, leaving his son William in charge. The brickyard sat idle for most of the 1890s as a prolonged economic depression wracked the nation.

Near the decade’s end the plant was sold to investors that included Philipsburg banker William P. Duncan. He soon bought out his partners. Under his leadership the Sandy Ridge Fire Brick Works supplied refractories that lined the fireboxes of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s steam locomotives. Lena Duncan oversaw the company after her husband’s death in 1904, until selling it in 1908 to Philipsburg residents Daniel Ross Wynn and his brother-in-law, James H. France, who were already making fire brick in Clearfield County.

Along the railroad north of the Sandy Ridge works, William J. Jackson established a fire brick plant about 1878. The little settlement that grew around it was named Retort, although the brickyard sometimes billed itself as being located in adjacent Powelton, a mining hamlet that preceded the establishment of the brickyard and where Jackson had operated the company store.

R.B. Wigton & Son began making refractories in 1882 on the Clearfield County side of the Moshannon Creek nearly opposite Philipsburg. Philadelphian Richard Benson Wigton had been engaged in coal-mining and iron-making ventures in Huntingdon, Centre, and Clearfield counties since the 1850s. After his death in 1895, the brickyard was sold and renamed the Philipsburg Fire Brick Works.

The Pennsylvania Railroad provided the Sandy Ridge, Retort, and Philipsburg brickyards with an efficient, all-season conduit to reach markets hundreds of miles away. The New York Central provided the same service for brickyards along Beech Creek, the mountain stream that formed much of the boundary between Centre and Clinton counties. The Clinton County Fire Brick Co. in 1900 opened a brickyard near the confluence of Beech Creek and Monument Run. From the mine – located high above the creek on the Clinton County side – a combination of narrow-gauge railroad and inclined plane brought the clay down to the plant, where more than one hundred men produced 20,000 brick daily.

Three miles upstream from what would become the community of Monument, two more brickyards took shape, both partly the result of land surveys done by Ellis L. Orvis. After graduating from Penn State in 1876, Orvis studied both the law and land surveying to continue a specialized law practice in land titles founded by his father. While doing surveys in the Beech Creek watershed for a client, he took note of clay deposits similar in extent and quality to those sourced by the brickyard at Monument.

In 1903 Orvis and other local investors organized the Hayes Run Fire Brick Co., whose plant could make 50,000 brick daily. The community that evolved with the brickyard was briefly called Orvis but later was renamed Orviston.

Upstream from Orviston, the investors established the Centre Brick & Clay Co. to produce light-colored building brick as well as fire brick. The plant opened in 1908, eventually reaching a daily output of 50,000. Ellis Orvis was also a principal in the Snow Shoe Fire Brick Co., which opened in 1910 at Clarence in Snow Shoe Township

The last refractories brickyard to be established was an outlier. Instead of flint clay, it used ganister, an extremely hard, quartz-rich sandstone. The resulting silica brick could withstand higher heat than flint clay brick and consequently commanded higher prices. The ubiquitous Ellis Orvis and several of his previous partners spearheaded the creation of the new plant in 1917 at Port Matilda, with Philipsburg coal operator James F. Stott as majority shareholder.

The plant started with a daily run of 35,000 brick and sat adjacent to the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Bald Eagle Branch. Ganister was obtained from a 500-acre tract that ran longitudinally above the plant along the northwest slope of Bald Eagle Mountain.

By the time the Port Matilda works began operating, Centre County’s refractories industry had already entered a second phase: merging existing facilities into larger companies whose reach and ownership extended beyond the county’s borders. Consolidation began with the purchase of the Retort brickyard in 1898 by Isaac Reese & Son. In 1902 Reese sold its holdings to Pittsburgh-based Harbison-Walker Refractories, which also acquired the brickyards at Philipsburg and Monument and was well on its way to becoming the world’s largest manufacturer of refractory brick.

Another series of consolidations started at Sandy Ridge. In 1911 Daniel Ross Wynn and J. H. France joined with Philadelphia investors to organize the General Refractories Co. (Grefco), combining their Sandy Ridge and West Decatur plants with facilities elsewhere. Both Wynn and France served in executive positions in the new company. By 1922 General Refractories – headquartered in Philadelphia – owned fifteen brickyards and ranked second to Harbison-Walker in daily output.

A third step toward centralized ownership occurred early in 1919 when Ellis Orvis and associates formed Eastern Refractories as a holding company to unite Superior Silica Brick, Centre Brick & Clay, and Snow Shoe Fire Brick. In addition, Eastern handled sales for the Hayes Run Fire Brick Co. at Orviston. Orvis served as chairman of the board. James Stott was president and held the largest stake in the new company by virtue of his Superior Silica holdings.

In August 1919, James Stott was killed in a coal mine accident and Eastern began to unravel. Superior Silica was spun off in a complex series of ownership changes, eventually becoming part of the McFeely Brick Company of Latrobe. General Refractories bought the Hayes Run operation in 1922.

The following year Columbus, Ohio-based Central Refractories purchased Centre Brick & Clay at Orviston and Snow Shoe Fire Brick. Central almost immediately found itself facing bankruptcy and put its Pennsylvania properties up for sale. When Centre Brick & Clay had no takers, its assets were liquidated. James H. France intervened to prevent a similar fate at Snow Shoe. He left General Refractories and, with help from a few other Philipsburg investors, bought the brickyard in 1924 and operated it as J.H. France Refractories.

At the outset of 1928, Centre County’s refractories industry counted 605 employees, down by about 200 since 1922. The decline reflected Centre Brick & Clay’s dissolution as well as the closure of Harbison-Walker’s obsolete Philipsburg brickyard. Refractories still ranked as the county’s second-largest industrial employer, behind coal mining (1,030 workers) and ahead of limestone quarrying and lime manufacturing (580 workers).

Brickyards operated only intermittently during the Great Depression of the 1930s, since their largest customers were themselves enduring lean times. General Refractories’ Sandy Ridge plant was most severely affected. It was idled in 1931 and remained shuttered for at least six years. It permanently closed in 1943.

World War II brought full employment to the brickyards, but difficult times resumed after when returned in 1945. Steel makers continued to thrive in the immediate post-war years, but improvements in the quality of refractories lessened the need for brick. Other industries likewise had less need for traditional fire brick. Refractory makers responded by closing older, labor-intensive brickyards.

Harbison-Walker suspended operations at Monument in 1949 and offered to sell the 70-odd company-owned houses that it owned in the community to employees. Two years later, some workers were called back to convert the plant to manufacture silica brick, using ganister trucked from Mount Union. The economics did not favor this modification, however, and operations ceased in 1953. The Retort works closed in 1954.

General Refractories bought the McFeely company in 1956 and closed the Port Matilda plant two years later. Grefco closed its Orviston works in 1962. As at Monument, employees had the opportunity to buy company-owned houses, but that was little solace to laid-off workers who faced long commutes to new jobs.

J.H France Refractories at Clarence successfully adapted to changing customer needs. Technological advances in manufacturing such diverse products as cement, glass, lime, pulp and paper, and petrochemicals required new kinds of refractories. Ownership changed several times over the years.

What is now known as Snow Shoe Refractories makes high-alumina refractory brick and also unshaped castables – premixed refractory aggregates that are pumped, poured, or sprayed on and then harden, preventing heat loss that can occur through joints and cracks associated with conventional bricks. The plant is the last vestige of one of Centre County’s most important industries.

Michael Bezilla

Sources:

Bezilla, Michael, “Centre County’s Once-Booming Refractories Industry: Nearly Extinct, All But Forgotten,” Mansion Notes, Fall 2024.

Brick and Clay Record, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003920579 (Accessed November 24, 2024).

Davy, Jim, All Company Towns Ain’t Bad: The Story of a Remote Mountain Community [Monument]. Beech Creek, Pa.: Howard T. Davy, 2011.

Krause, Corinne A., Refractories – The Hidden Industry: A History of Refractories in the United States, 1860-1985. Westerville, Ohio: American Ceramic Society, 1987.

First Published: December 15, 2024

Last Modified: December 18, 2024