When slavery is mentioned in the history of Centre County, it is usually in the context of abolitionism and the Underground Railroad. However, the county also has its own local history of slavery and slave ownership.

White settlement in the county began in the 1750s with the arrival of Irish-born land speculator and politician James Potter (1729-89). Like Potter, the earliest settlers were Irish Protestants, mainly Presbyterians. At the end of the century, Central Pennsylvania became a vital center for the charcoal iron-making industry. Most of those key early settlers and ironmasters owned slaves.

Slavery was a well-established institution in the Pennsylvania colony. The colony had about five thousand slaves in the 1720s, rising to ten thousand in the mid-1750s, and that number peaked dramatically during the French and Indian War period, around 1759-65. These were the years that white colonists were first venturing into Central Pennsylvania. One local history reported General Potter “selling tracts to Scots-Irish settlers coming with their slaves from the south through the Seven Mountains.”

One of the earliest accounts of the Centre County settlement comes from Virginia Presbyterian minister Philip Fithian, who traveled through the border country in 1775. In Penn’s Valley, he was hosted by James Potter, near Centre Hall. When he woke on an August Sunday, he “rose early, before any in the family, except a negro girl.” She was probably called Daphne. When Potter’s will was proved in 1789, he listed a good deal of property, which included “his sword, riding furniture, his negro man Hero, and mulatto man Bob.” Potter bequeathed part of his estate “to his daughter Martha, wife of Hon. Andrew Gregg . . . to Mrs. Gregg he gave his negro slave Daphne, and Daphne’s daughter Sal and son Bob.” Andrew Gregg went on to serve as U.S. senator from Pennsylvania from 1807 to 1813.

In 1780, Pennsylvania famously took a pioneering lead among the emerging states in formally abolishing slavery, but this was a very gradual measure, and a grandfather clause allowed the continued enslavement of registered slaves. Moreover, children born to slaves were bound through indenture until the age of 28. Not until 1847 was Pennsylvania entirely free of slavery.

Far from ending in 1780, slavery in Centre County actually expanded at the end of the century. In Gregg Township in the 1790s, the wealthy slave owner James Cooke arrived from Lancaster County to build a saw-mill and a grist mill. In the same decade, the first white settlers of remote Curtin Township were two brothers from Maryland who “shouldered their rifles, and accompanied by a single negro slave wended their way northward through the wilds of Pennsylvania until reaching Centre County.”

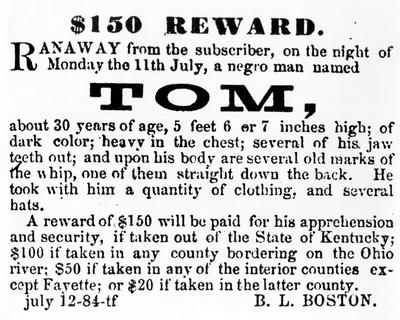

One entrepreneurial slaveowner was John Patton, an Irish Protestant immigrant and a mainstay of the local Presbyterian network. In 1792, he joined with Colonel Samuel Miles to build Centre Furnace. Other members of the Miles family had owned slaves in the region since the 1770s. In 1799, Patton advertised a reward for two runaways. These were “Negro man John about 22, also Negro girl named Flora about 18, Slender made, speaks bad English and a little French. Has a Scar on her upper lip and letters branded on her breast.”

John and Flora were presumably domestics in Patton’s house, as virtually all of the local slaves were maids, cooks, or coachmen. Some reasonable deductions can be made about the background of at least one of the people mentioned. The reference to Flora’s French suggests that she had been brought to America from Santo Domingo. Following the Haitian Revolution of the 1790s, many slave-owning refugees had come to Philadelphia. The brand on her breast was almost certainly a penalty inflicted for an earlier escape attempt.

So much of the evidence for slaves depends on casual references and legal cases. In 1802, the first capital case tried in the new Centre County involved the Bellefonte slave Daniel Byers, “the property of Mr. J. Smith.” Byers was executed for murdering a free mulatto in a dispute over a white woman. Between 1803 and 1820, some of the best-known local families registered the birth of children to their slaves, and those children would be subject to indentures that made them virtual slaves. These owners were mainly the ironmasters, including Philip Benner, James Harris, and Joseph Miles.

Slaves constituted a small minority of the early population. By 1800, probably forty or fifty slaves lived in Centre County. By 1830, the county had 18,763 White inhabitants, and 263 Blacks, almost all free. Still, even at this late point, Potter Township had four female slaves, and one male.

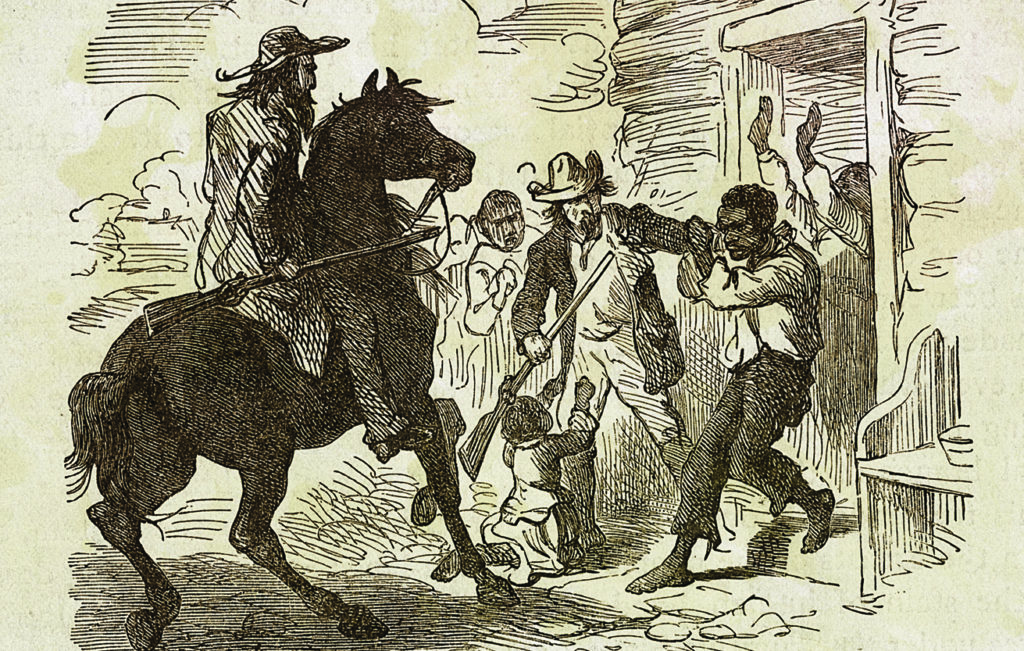

The slavery that still flourished in Southern states had its impact on the county and threatened Black residents. In 1826, some Virginian slave-catchers arrived at Bellefonte to seize two runaways. These “were paraded through the streets, bound hand and foot with ropes, and taken to jail. There was many an eye to pity but none to save.” A local judge examined the credentials of the owners and granted their right to seize their human property. In 1833, “a colored woman, who had lived in Bellefonte for over six years, married, and, having several children, was remanded into slavery by the court in Bellefonte.”

Over the following decades, the county developed a militant anti-slavery tradition, with a lively Underground Railroad. Bellefonte had a substantial African American community and supported an AME church. The area’s Scotch-Irish Presbyterians became mainstays of the Republican cause and passionately supported Abraham Lincoln in the Civil War. Pennsylvania’s wartime governor was Andrew Gregg Curtin, a descendant of both General Potter and Andrew Gregg.

However, slavery enjoyed some support in the county. Peter Meek, the controversial editor of the Bellefonte Watchman, regularly spoke out against a war fought to end slavery. He was arrested several times for his editorials considered treasonous for critizing the draft.

In modern times, abolitionism has attracted most historical attention, and the world of people like Daphne and Flora have been all but forgotten.

Philip Jenkins

Sources:

Linn, John Blair. History of Centre and Clinton Counties, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1883.

Ross, Marc Howard. Slavery in the North: Forgetting History and Recovering Memory. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Tomek, Beverly C. Slavery and Abolition in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania History Association, 2021.

First Published: March 3, 2022

Last Modified: February 24, 2025