The eighteen ironworks that operated across Centre County throughout the nineteenth century, including Centre Furnace, Eagle Ironworks, Rock Ironworks, Harmony Forge, Logan Furnace, and Pennsylvania Furnace, followed practices developed in Europe centuries earlier.

The county had all the resources necessary for making iron: timber, limestone, and iron ore. It also had two major streams, Bald Eagle Creek and Spring Creek, which, along with their branches, provided the water supply needed to power furnace machinery. There were four steps in the production of iron: making charcoal from timber to fuel the furnaces and forges; digging iron ore from shallow mines and cleaning it; separating the iron from ore in cold-blast furnaces; and converting the pig iron into wrought iron at forges.

The process began by burning wood in mounds to produce charcoal. Crews went into the nearby forests during the autumn and winter months to cut trees. Any kind of wood could be used, but hardwoods (ash, hickory, and oak) made the best charcoal. Once they were felled, the crews trimmed the small limbs and cut the trees into 4-foot lengths. The wood was stacked into cords 4 feet wide, 4 feet high and 8 feet long. A good woodcutter averaged three cords a day. Ironworks needed 10,000 to 12,000 cords of woods each year to operate. The average acre of forestland yielded about 30 cords, which meant that 200 to 300 acres of timber needed to be cleared annually.

Making coal was done between April and October. Led by a “collier,” crews found a level clearing in the forest near the stacked cordwood for the pit. A circular area about 30 feet in diameter was marked out and a small chimney made of wood sticks was built in the center. The cut wood was stacked on end tightly around the chimney to the edge of the the circular pit.

Once the first layer was in place, second and third layers were added. Finally, a layer of wood was put horizontally on the top, forming a rounded mound about 15 feet high. The mound was covered with small branches and sealed with wet leaves and soil.

Several holes were cut into the mound to allow air to enter. The chimney then was filled with twigs and leaves. It was set on fire and the chimney capped so that the fire would smolder. The purpose of coaling was to pull the moisture from the wood, leaving behind pure carbon. A “burn” took from ten to fourteen days, and during the process the mound shrank in size by about a third. After the fire was out, crews removed the top and raked the coal into piles. The coal was loaded into wagons and taken to a shed where it was stored until needed for the furnace.

The iron ore used in the county’s ironworks was found in deposits near the surface. Using picks, hammers, and shovels, crews dug out the ore in open pits that were 10 to 50 feet deep. It was carried by wheelbarrows to a spot where it was separated from the waste material by a process known as “dry screening.” The clumps of ore and waste material were spread onto a floor. Heavy cast-iron breakers, driven by a mule or horse, were driven back and forth over them. The crushed ore was separated by hand using screens. The clean ore then was loaded onto horse-drawn carts and taken to the furnace.

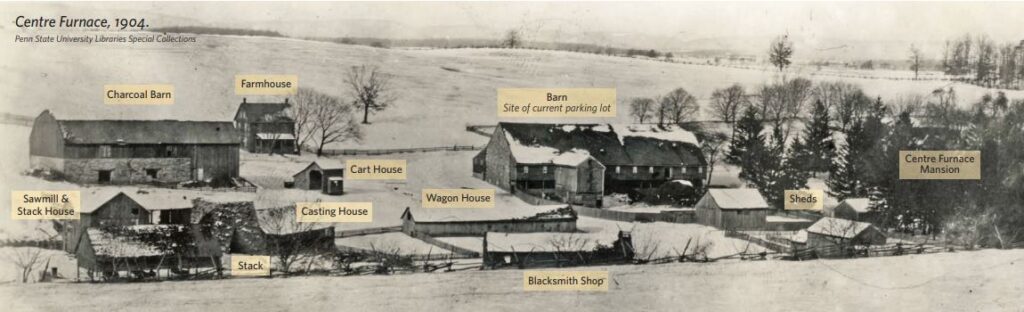

The furnace was a truncated, stone pyramid about 30 feet high and set upon a 25-foot square base. Running from the top to the bottom of the stack was a hollow bottle-shaped tunnel. The mouth was about 2 feet wide and the tunnel gradually widened to about 8 feet at the “bosh.” Below the bosh, the tunnel narrowed into the “crucible.” At the base of the crucible was the “hearthstone.” Two pipes or arches on the side of the furnace at the base provided access to the interior. One was called the “tuyere arch” through which compressed air was forced into the furnace. The other was the “casting arch” where the pig iron was removed. A “blast house” next to the furnace housed the waterwheel and bellows that sent the air into the furnace.

When the furnace was ready for use, a “filler” and his crew loaded it with charcoal. The charcoal was set on fire and allowed to burn down into the tunnel. The furnace was refilled with charcoal and allowed to burn back. After several days of burning the charcoal, a bed of coals was inside.

The furnace then was “charged,” with the iron ore, charcoal, and limestone placed in the furnace, and the blast was turned on. The limestone acted as a fluxing agent that helped remove impurities from the ore. Flowing water from a stream powered a water wheel which pumped bellows that blew air into the furnace keeping it at the necessary 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Under the intense heat, the iron in the ore liquefied and sank to the bottom of the crucible. The impurities formed a less heavy, molten waste called “slag” which floated on top.

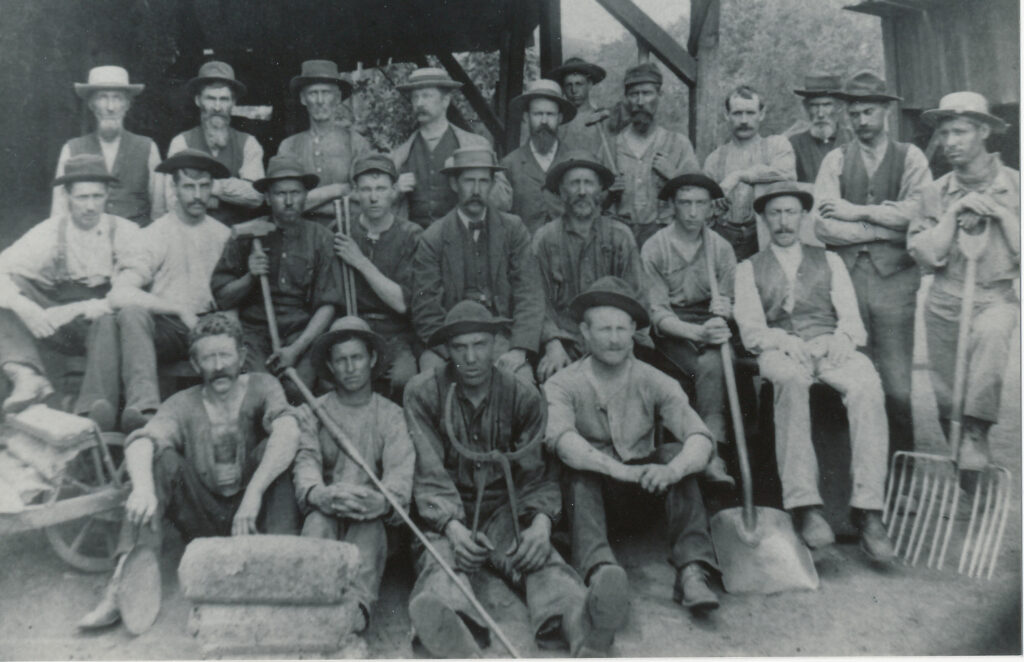

When the iron was ready for tapping, workers drained the molten slag out of the way. Then they directed the molten iron into molds that had been dug in the dirt floor of the casting room. The molds had pattern that resembled a sow with a litter of sucking pigs which gave “pig iron” its name. After cooling, the pig iron was shipped to the forge. Each tapping produced about one and half tons of pig iron. Furnaces operated twenty-four hours a day with crews of twenty to thirty men working twelve-hour shifts.

The forges used two kinds of hearths to melt the pig iron and make it more malleable: “finery” hearths and “chafery” hearths. The pig iron was placed on charcoal in the finery hearth and the fire lighted. When the iron reached the melting point, it dripped to the bottom of the crucible. Workers lifted the mass of molten iron and exposed it to blasts of air from bellows. This removed the carbon and other impurities so the wrought iron could later be shaped.

A giant power finery hammer pounded the iron into a thick square slab of iron called a “bloom.” The blooms were cut in half and returned to the hearth to be heated again and the power hammer was used to shape them to resemble a square-end dumbbell call an “anchony.” The anchonies were put into the chafery hearth where they were alternately heated and pounded by a hammer into bars of wrought iron.

By the mid-1850s, charcoal-iron production gradually was being replaced with cheaper and more efficient coal-fueled operations. However, the cost of shipping coal to Centre County proved to be too expensive. Unable to compete with other iron operations in the state, the county’s ironworks began to close. The last remaining charcoal-iron furnace in the county and the last in Pennsylvania, Eagle Ironworks, ceased operation in 1922.

Ford Risley

Sources:

Bining, Arthur Cecil. Pennsylvania Iron Manufacture in the Eighteenth Century. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission, 1938.

Eggert, Gerald G. Making Iron on the Bald Eagle: Roland Curtin’s Ironworks and Workers’ Community. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2000.

Stephens, Sylvester K. The Centre Furnace Story: A Return to Our Roots. State College: Centre County Historical Society, 1985.

First Published: August 30, 2021

Last Modified: April 4, 2022