A quest for natural resources shaped the development of Centre County’s rail network, beginning in 1859 when the Bellefonte and Snow Shoe Railroad began hauling coal and timber from the Mountaintop area to the Bald Eagle Valley.

At Milesburg, the Bellefonte and Snow Shoe Railroad transloaded much of its tonnage to boats on the Bald Eagle and Spring Creek Navigation canal for forwarding via Lock Haven to eastern markets. That arrangement lasted until 1865, when the Bald Eagle Valley Railroad was completed between Tyrone and Lock Haven, giving shippers an all-rail route to eastern and western markets.

The Bald Eagle Valley Railroad and two other rail lines in the county, the Tyrone and Clearfield and the Lewisburg and Tyrone, functioned as components of the Philadelphia-based Pennsylvania Railroad. Although local investors started all three lines, all ran short of capital and welcomed the Pennsylvania Railroad’s investment in return for giving that railroad a controlling interest. All three survived as legal entities until the early 1900s, but they were not operating companies.

From Tyrone on the Pennsylvania Railroad main line, the Tyrone and Clearfield Railroad built northward up and over the Allegheny Front to the Moshannon Valley, reaching Philipsburg in 1863 and Clearfield in 1869. Dozens of coal mines, brickyards, and sawmills opened along its route. Until the late 1890s, the Tyrone and Clearfield Railroad (renamed the Clearfield Branch) was the Pennsylvania Railroad’s largest originator of bituminous coal, in some years hauling more than 4 million tons down to Tyrone.

The Lewisburg and Tyrone Railroad began life as the Lewisburg, Centre, and Spruce Creek Railroad. The Pennsylvania bought into the company – which it reorganized as the L&T – primarily to block other railroads from using the route through the valleys of Union and Centre counties as part of a possible east-west trunk line that might compete with the Pennsylvania Railroad’s own Harrisburg-Pittsburgh line. Construction proceeded slowly; as rails neared Lemont, the Pennsylvania Railroad decided to make Bellefonte the western terminus instead of Tyrone, opening the line for through traffic in 1885. The Pennsylvania Railroad aimed to blunt a westward thrust into the county by the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, which was already buying property in Bellefonte.

Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania Railroad built eastward from Tyrone to serve Andrew Carnegie’s new iron ore-mining venture at Scotia, reaching that point in 1881.The gap between the L&T’s two sections held little prospect for traffic except at State College; and that community was already served by the Bellefonte Central Railroad, which connected with the Pennsylvania Railroad at Bellefonte.

The Beech Creek Railroad, a New York Central subsidiary, entered northern Centre County from the east in search of high-quality coal. It reached Snow Shoe in 1884 before extending into western Pennsylvania. A branch linked the main line at Munson with Philipsburg. The Beech Creek was absorbed by its parent in 1899. A smaller New York Central adjunct was the Central Railroad of Pennsylvania, which ran from Mill Hall through the Nittany Valley to Bellefonte.

Opened in 1893 to compete with the Pennsylvania Railroad for Bellefonte’s iron trade, the Central Railroad was thought to be a potential launching pad for the New York Central to build to the Broad Top coal fields in Huntingdon County. However, after the two iron furnaces it served in Bellefonte closed in 1910-11, the Central Railroad depended heavily on passenger and express revenues, which proved grossly inadequate. The railroad ceased operations in 1918 and was liquidated soon thereafter.

As the Nittany Valley’s iron industry declined, the limestone and lime trade boomed. The exceptional purity of the Valentine Formation, which underlay parts of the valley, made it ideal for the manufacture of lime, increasingly in demand by industry.

The Pennsylvania Railroad served two of Bellefonte’s “Big Three” producers: the Warner Company and Whiterock Quarries. The Bellefonte Central served the third, National Gypsum, and handed off its tonnage to the Pennsylvania Railroad. Whiterock exited the lime business after World War II; its place among the Big Three was taken by Standard Lime. The Standard mine and lime plant underwent several changes in ownership, eventually becoming a property of international lime and stone producer Graymont.

Traffic on the Bald Eagle Branch also surged. In the early 1900s, it became a component of a fast-freight route between the Midwest and New England. Millions of tons of coal also moved over the branch annually from western Pennsylvania to upstate New York and New England. The trade magazine Railway Age in 1912 hailed the branch as the busiest single-track route in North America, witnessing the daily passage of about thirty trains in each direction.

The Bald Eagle Branch also hosted the county’s only named, first-class passenger train, the Penn-Lehigh Express, introduced in 1916 on a daytime schedule between Easton and Pittsburgh via Sunbury, Williamsport, and Lock Haven. The remainder of Pennsylvania Railroad passenger service in the county consisted of coach-only local trains.

For a few years beginning in 1885, the New York Central offered sleeping car service between Philipsburg and Philadelphia in concert with the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. Otherwise the Central’s trains were the same kind of no-frills locals found on the Pennsylvania Railroad. After World War I, the emergence of a state system of paved highways and widespread automobile ownership whittled away at the passenger trains. Discontinuance of a pair of Altoona-Lock Haven trains on the Bald Eagle Branch in 1950 brought an end to all scheduled passenger service in the county.

Around the time of the merger, some once-prominent county trackage was abandoned: the Clearfield Branch between Osceola Mills and Vail, the former Beech Creek line from Mill Hall to Snow Shoe, and the L&T between Coburn and Mifflinburg. Traffic on the Bald Eagle Branch nearly dried up as the Penn Central realigned through-train routes. The merger failed to yield the anticipated cost savings. Penn Central was losing a million dollars a day, service deteriorated, and the company declared bankruptcy in 1970.

The principal railroad lines in the county in the early 1900s remained essentially unchanged until the 1960s. In 1968, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central railroads — both struggling financially — merged to form Penn Central. The hope was that enough duplicate trackage, facilities, and equipment could be eliminated to make the new road profitable.

Concluding that Penn Central had no viable future, Congress in 1976 created Conrail, a federally backed entity that consolidated Penn Central with five other bankrupt Northeastern railroads. To foster Conrail’s success, Congress in 1980 began to free the railroad industry from the strict economic regulation that had characterized it since the early 1900s.

As a result, Conrail experienced a turnaround, reporting net earnings for the first time in 1981 and remaining profitable every year through its 1999 shared purchase by Norfolk Southern Railway and CSX Transportation. A component of deregulation permitted railroads to abandon or sell any line that lost money or had earnings below the cost of capital.

On that basis, in 1983 Conrail announced it would dispose of the Bald Eagle Branch and all lines served from Bellefonte. The Susquehanna Economic Development Authority-Council of Governments established a Joint Rail Authority to preserve rail service in Centre and four other counties where Conrail lines were threatened with extinction. The authority purchased the lines in 1984 and contracted with veteran railroad manager Richard Robey to operate freight service.

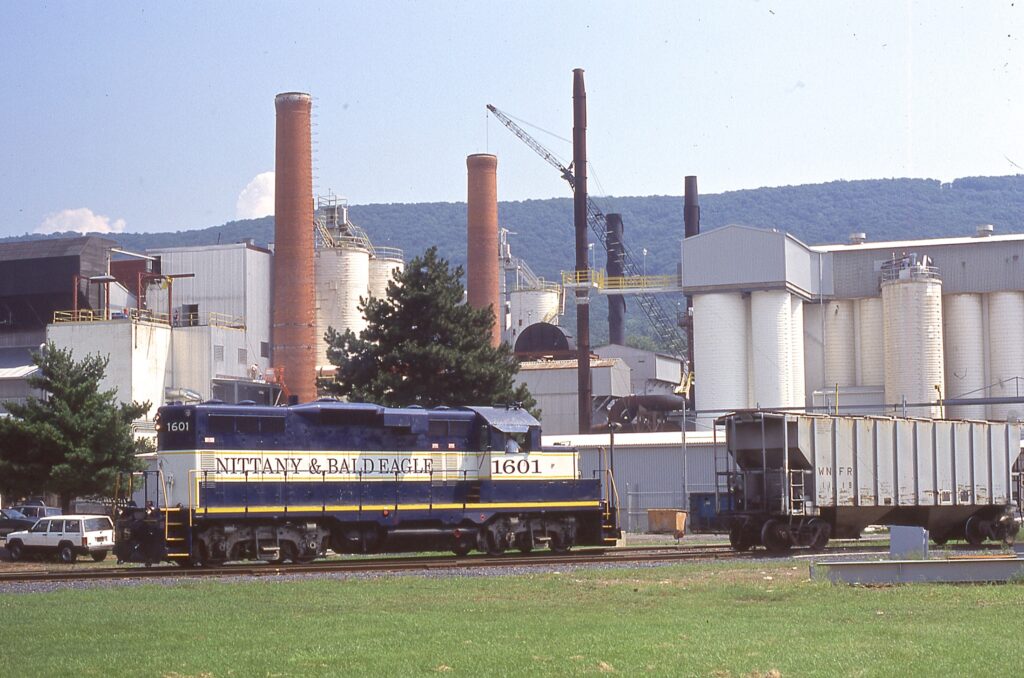

Under a single ownership umbrella, Robey created individual railroads for each geographic area. The Bellefonte-based company was the Nittany and Bald Eagle Railroad, whose traffic grew many times over from the 750 carloads it handled in 1985. While lime and limestone remained the core of its business, the railroad diversified its traffic to include such products as plastic pellets, cement, liquid asphalt, wood pulp, and lumber. It remains an important economic lifeline for many Centre County industries.

Michael Bezilla

Sources:

Bezilla, Michael. Branch Line Empires. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017.

Davy, Jim. All Company Towns Ain’t Bad. Beech Creek, Pa.: Jim Davy, 2011

First Published: June 10, 2021

Last Modified: February 24, 2025