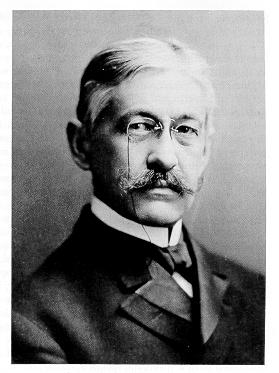

Edwin Erle Sparks, Penn State’s eighth president, served from 1908 to 1920. Using his skills in outreach, he took advantage of the public’s growing appreciation for the value of Penn State programs to build the college’s popularity to levels never achieved before.

Sparks was born in Newark, Ohio, in 1860 and earned a B.A. in history from Ohio State in 1884 and an M.A. from Harvard in 1890. He taught high school and was a school superintendent in Ohio before coming to Penn State to be head of the Preparatory Department from 1890 to 1895. (Penn State, like most nineteenth-century colleges, offered two years of pre-collegiate instruction before community high schools became common. Its Preparatory Department closed in 1908.)

Sparks left in 1895 to take up graduate work at the relatively new University of Chicago, where he earned his doctorate in history in 1900. In the next eight years, Sparks proved himself a prodigious scholar and teacher. He wrote eight books in American history, rose to the rank of professor, served for a time as dean of the University College, and chaired the educational committee of the Chicago Centennial of 1893.

Sparks also became one of Chicago President William Rainey Harper’s stalwarts of the extension lecture courses, one of the university’s most distinctive features. During his years at Chicago, Sparks taught almost a third of the extension courses.

After the death of President George W. Atherton, Sparks returned to Penn State as its president. He found the college in turmoil under the acting presidency of James A. Beaver. College Vice President Judson P. Welch battled several school deans for administrative control, and students went on strike against what they perceived as overbearing faculty.

Sparks’ genial personality returned calm and a sense of mission to the campus. The growth of Penn State’s technical curricula and agricultural research during the Atherton years had created a reservoir of latent good will for the college, and Sparks sought to build on that. Sparks toured the Commonwealth giving as many as fifty speeches a year extolling the virtues of the college.

The Extension Service was founded with the federal Smith-Lever Act in 1914, and Sparks advanced its programs in every possible discipline. “Taking the College to the People” was Sparks’ motto for extending the instructional and research programs of Penn State to all corners of the state.

Traditionally, agriculture had been regarded as the college’s responsibility in extension courses, and during the Atherton period this effort had expanded through short courses, bulletins, and the work of county agents. Sparks introduced a formal program to “extend” instruction and the dissemination of research results — a program later called “Continuing Education” and then “Outreach.” New curricula in business, liberal arts, education, pre-medical and pre-legal studies were created, as well as engineering and mining experiment stations to conduct research.

In ten years, regular student enrollments tripled to 3,300 students, with summer sessions growing from fewer than 200 to more than 1,000. Sparks fostered the growth of student government, fraternities, and other organizations. Women’s enrollments grew, and women had their own organizations and self-government. Along with these advances came the first deans of men and women and a student advisory system. America’s entry into World War I in April 1917 had a grave impact on President Sparks and Penn State.

The college had already been under stress with insufficient funding to support growing enrollments. Now it began to work on a war footing, first with the creation of a Reserve Officer Training Corps. In the spring of 1918, troops began to be stationed on campus for specialized training. That summer, virtually all able-bodied male students were enlisted in the Student Army Training Corps, and military officers took over most instruction, with regular college classes largely suspended. When the Spanish Flu epidemic peaked in October 1918, the pressure mounted. The Armistice was signed the following month, but demobilization still challenged the college’s administration.

In 1920, Sparks resigned the presidency to return to teaching. He died in State College on June 15, 1924. The Sparks Building on campus, headquarters of the College of the Liberal Arts, and Sparks Street in the State College Borough are named for him.

Lee Stout

Sources:

Bezilla, Michael. Penn State: An Illustrated History. University Park: Penn State University Press, 1985.

Runkle, Erwin W. The Pennsylvania State College, 1853-1932: Interpretation and Record. The 1933 manuscript was published in 2013 by the Nittany Valley Society.

First Published: May 20, 2021

Last Modified: October 2, 2021