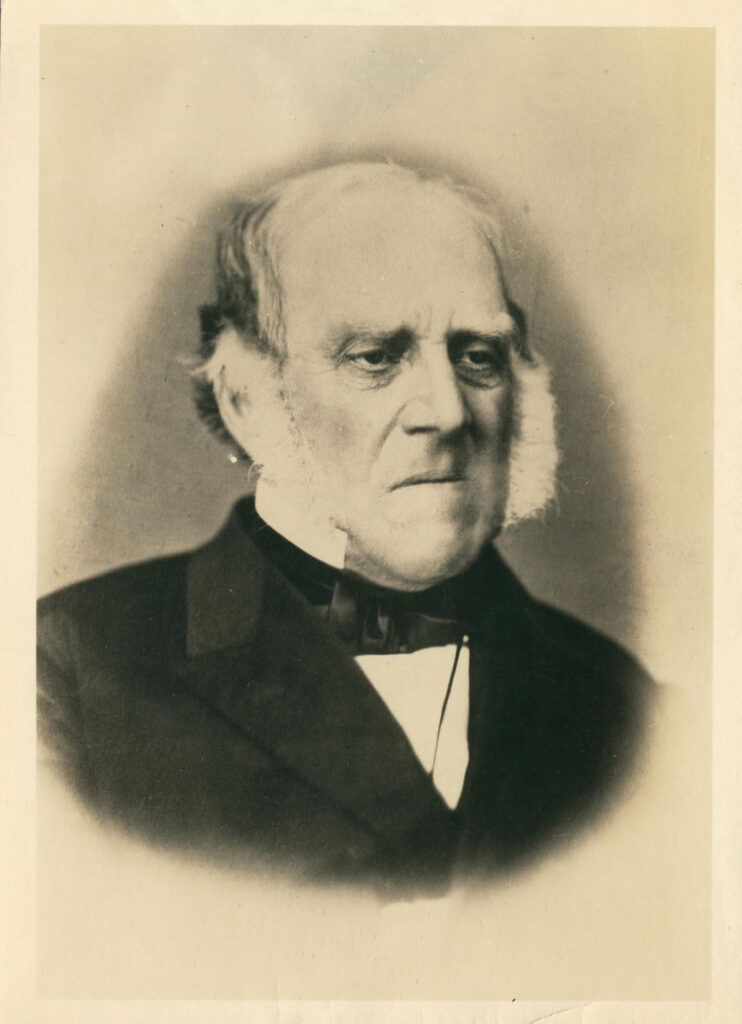

Frederick Watts served as founding president of the Board of Trustees of the Farmers’ High School / Agricultural College of Pennsylvania from 1855 to 1874. He played an integral role in establishing the college in Centre County and securing its federal and state land-grant designation.

Watts rose to prominence during the first half of the nineteenth century as a lawyer, reporter for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, judge, and president of the Cumberland Valley Railroad. His true interests, however, lay in agricultural improvement and in raising the economic, social, and political standing of Pennsylvania’s farmers.

As a “gentleman farmer,” the Carlisle native made numerous contributions to the advancement of agriculture, including innovative and more efficient farm and barn design. To the state’s farmers, he introduced Mediterranean Wheat (1839), which ended the annual depredations of an insect pest that ravaged the crop, as well as the McCormick Reaper (1840).

In 1851, he was elected founding president of the new Pennsylvania State Agricultural Society. He inaugurated large state fairs to showcase agricultural products and practices and establish class-consciousness among the farming community. He also urged the establishment of county agricultural societies.

Most significantly, he used his position to advocate for an agricultural college that would employ science to improve farming practices. He drafted the plans and legislation that led to the chartering of the Farmers’ High School of Pennsylvania in 1854 and then, because the charter was flawed, to the second charter signed by Governor James Pollock on February 22, 1855.

Watts was instrumental in establishing the school in Centre County. He and fellow trustees visited Centre Furnace Mansion on June 26, 1855, to view the 200 acres offered for free by ironmaster James Irvin. After the trustees viewed other sites, they met in Harrisburg on September 12, 1855, and debated the merits of the various offers. Ultimately, the trustees approved Watts’s motion for the Centre County site, which presented the best advantages of “soil, surface, exposure, healthfulness and centrality.”

Watts adroitly directed the school while it was built from scratch, securing the first state appropriation of $25,000 in 1857 to finance the College Building (later Old Main). He hired the brilliant Evan Pugh as founding president, who with Watts and Trustee Hugh McAllister of Bellefonte, quickly made it the first successful agricultural college in America (renamed in 1862 as the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania). By 1864, the school enrolled 146 students educated on the highest scientific standards of the day.

Most importantly, Watts, Pugh, and their agricultural allies secured the College’s designation as Pennsylvania’s recipient of funds derived from the federal Morrill Land-Grant College Act. The act established colleges that would introduce agriculture and engineering, among other scientific and liberal studies, for the benefit of the “industrial classes.”

After Pugh’s untimely death in 1864, Watts defended the institution against legislative attempts to wrest the land-grant college designation away and distribute its funds to additional colleges in Pennsylvania. He engineered a desperation move asking that the state either give the entire land-grant fund to the college or take it over entirely, assuming its debts and management.

The strategy worked, and in February 1867, the legislature finally approved the Agricultural College as the exclusive recipient of the Morrill Act funds. The act endowed the college with $440,000 from the sale of federal lands apportioned to the state on the basis of population.

But for all his success in launching the college and defending it against legislative usurpers, Watts nearly brought it to the brink of closure through a series of ruinous presidential appointments of men unsuited to the task of building a scientifically grounded land-grant college. From 1864 through 1880, Presidents William Allen (1864-66), John Fraser (1866-68), Thomas Burrowes (1868-71) and James Calder (1871-80) encountered financial difficulties and enrollment declines. They introduced wildly divergent curricular experiments — with which Watts and the trustees concurred — that pulled the college away from its federal land-grant mandate in which agriculture and engineering were to be the “leading object.”

This “era of drift” angered agricultural constituents, incurred legislative investigations, and turned the institution into a “mere literary college,” in the words of an alumnus. The trustees formed a faculty committee to revise the curriculum and “correlate” it with the land-grant act. In 1882, they hired George W. Atherton of Rutgers as president, who over his 24 years brought the institution into success for the twentieth century.

By then Watts was long gone. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him commissioner of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1871. Watts continued to champion land-grant colleges and advocate for new agricultural research stations. He expanded the department’s seed distribution program to aid the developing west and recovering south, and advanced its scientific agenda by introducing microscopy to study plant diseases and introducing forestry.

He retired in 1877, returned to Carlisle, and died on August 17, 1889. In the words of historian (and Penn State School of Agriculture dean) Stevenson Fletcher, “from 1850 to 1880, he was by far the most outstanding figure in Pennsylvania Agriculture.”

Roger Williams

Sources:

Williams, Roger L. Frederick Watts and the Founding of Penn State. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021.

Fletcher, Stevenson W. Pennsylvania Agriculture and Country Life, 1840-1940. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1955.

First Published: April 3, 2022

Last Modified: February 28, 2025