Before European colonists arrived, Pennsylvania was an estimated 97 percent forested. Centre County is in an ecological region in which the aboriginal forest was dominated by white pine and hemlock, both of which had lucrative industrial applications that attracted colonists and entrepreneurs.

White pine trees grow tall and straight, making them ideal for masts on ships. Hemlock trees were coveted for their bark, which yields tannic acid that in turn is used in the production of leather. Pennsylvania’s first sawmills started operating in the Philadelphia area as early as the 1680s, almost immediately after William Penn founded the colony.

Loggers reached Centre County after exhausting the forests of southeastern Pennsylvania. By the mid-1800s, many communities in the county had small water-powered sawmills as their primary industrial facilities. Large tracts of forest were purchased by ironmakers to obtain trees that were slowly cooked into charcoal, which in turn fueled iron furnaces.

Smaller operators also often acquired forested tracts to harvest trees for the construction industry. In many cases, these forested lands were purchased for relatively inexpensive sums, from county officials who craved tax revenues while trying to attract industry to the area.

Central Pennsylvania’s first notable lumber baron, John Ardell Jr., established a logging firm in Bellefonte in 1874. Ardell made a substantial fortune, as well as highly placed political enemies, and his stately mansion still stands on Linn Street in Bellefonte.

When lumber harvesting matured into a large-scale industry, most of Centre County’s timber traveled the waterways to the north, eventually arriving in Williamsport which hosted industrial sawmills and manufacturers of wood products. Vast amounts of fallen timber were also used to fuel charcoal iron furnaces, like that at Pennsylvania Furnace. A significant portion of Centre County’s fallen trees were processed into props for mining tunnels.

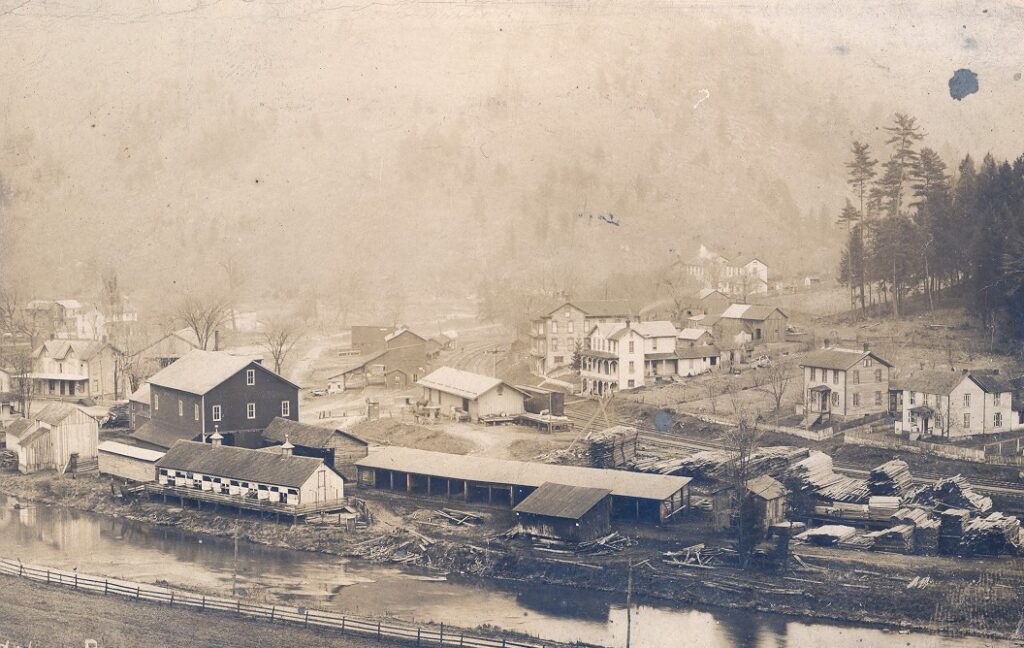

Logging firms often housed workers at hastily constructed camps that developed into functioning towns with hundreds of residents and full services. Many such towns have since disappeared, having been abandoned when local trees ran out and the loggers moved on. Ironically, the forest has reclaimed most such settlements.

One such town near the present Black Moshannon State Park was called Sober and appeared on maps in the late 1800s. The town was not named after the residents’ attitudes toward liquor, but instead after local logging entrepreneur C.K. Sober. Explorers of Moshannon State Forest may find dim evidence of such old settlements, usually in the form of crumbling stone walls and collapsed dams. Several such ruins can be found along Six Mile Run in Rush Township.

Another dimly visible logging ghost town called Poe Mills can be found at the present Poe Paddy State Park in Haines Township. The town was served by the Lewistown and Tyrone Railroad. That railroad’s former route around the park has been converted to gravel roads for nature lovers, while a former railroad tunnel through a ridgeline provides a unique thrill for the users of a bike trail.

Central Pennsylvania’s rugged topography presented a challenge for the region’s earliest loggers, because trees felled in remote locations were difficult to transport to market. Engineers tackled the problem by devising the splash dam. A typically earthen dam was built across a creek, with a wooden gate that could be opened and closed.

Workers placed logs in the artificial lake that formed behind the dam. When all was ready, the gate was opened and the pent-up water would surge forth, carrying the logs down the watercourse. Their destination was usually a sawmill at a downstream location, or sometimes larger rivers like the West Branch of the Susquehanna on which logs could be floated to market more easily.

The process upon opening the dam created a serious challenge, as the chaotic surge downstream was not easily controlled. According to historian Tom Thwaites, workers were assigned to run alongside the water and push beached logs back into the torrent before it subsided. This occupation apparently resulted in many deaths.

After the logs surged downstream, the gate was closed and the process began anew. Splash dams were used widely across central Pennsylvania during the early logging era. They created significant environmental destruction and altered the natural courses of streams in ways that still have ecological effects today. There were probably dozens in Centre County alone, and a well-preserved specimen can still be seen, via the Chuck Keiper Trail, along Eddy Lick Run in Curtin Township.

Splash dams started to become obsolete in the 1880s as narrow-gauge railroads enabled horse-drawn carts and small locomotives to reach more and more rugged areas. The splash dam at Eddy Lick Run is severed by a right-of-way that carried the railroad that replaced it, and that railroad is now long-gone itself.

These narrow-gauge railroads proliferated throughout Pennsylvania during the late 1800s. Most were abandoned when the logging companies moved on, and the logging companies often removed the iron rails and reused them for new tracks at their later areas of operation.

The rails were almost completely scooped up by collectors responding to calls for scrap iron during the two World Wars, while the cross ties deteriorated. The result was flat grassy lanes that can be easily found throughout Pennsylvania’s current forests, with hundreds of miles of such overgrown grades in Centre County alone. Many such grades still show rock retaining walls, artificially raised beds, cuts through low ridgelines, and the foundations of bridges that collapsed and washed away.

Many such lanes are now used as the routes for hiking and biking trails, and occasionally forestry roads. A good example of this pattern can be found in the Rock Run area east of Black Moshannon State Park, where a 12-mile network of skiing/hiking trails was built almost entirely from old railroad grades.

By the end of the logging era, the non-residential areas of the county were almost entirely portioned out to logging firms. Due to unreliable surveying methods, the boundaries between the parcels owned by neighboring companies were highly contested due to the value of the timber to be harvested. A company would not dare to harvest trees belonging to a competitor, and the fuzzy boundaries sometimes created no man’s lands where the trees survived due to competing companies trying to stay off each other’s turf.

Ironically, this process created the few patches of undisturbed old-growth timber remaining in Pennsylvania. A beautiful example of this effect, featuring immense hemlocks and white pines confirmed to be more than 500 years old, can be found at Alan Seeger Natural Area a few miles south of Tussey Mountain Ski Area. (This natural area is in northern Huntingdon County, just over the Centre County line.)

The virgin forests of Centre County were almost entirely clearcut by about 1900. Loggers sought to maximize profits, felling every tree in sight with no concern for conservation, and the Commonwealth did not yet have regulations or inspectors to provide oversight of the rapacious clearcutting. The result was severely damaged ecosystems and abandoned infrastructure. By the end of the era, most of Pennsylvania consisted of “stumps and ashes” as described in a 1995 Commonwealth forestry report.

After the loggers moved on, settlers often arrived hoping to convert the cleared areas to agriculture. This was successful in the county’s valleys, where farms were established. The effort was much less successful on the ridges and the high plateau region of the western part of the county, where farmers often attempted to convert clearcut areas to pasturelands and ranches. Such efforts typically failed and those areas reverted to forest, but with an altered ecosystem of oak-dominant hardwoods without most of the aboriginal white pine and hemlock.

Even before the logging industry had tired of the region, the Commonwealth began to reclaim land in order to restore the forests, typically buying it cheaply from desperate owners who had failed to turn their lands into pasture or who sought forgiveness for delinquent tax bills. Moshannon State Forest, Centre County’s largest tract of protected land, was established via this process in 1898 and grew steadily in the following decades.

The county also contains a segment of Rothrock State Forest, which was established via the same process. A logging firm called William Whitmer & Sons Company sold its clearcut lands to the Commonwealth starting in 1902, resulting in Poe Valley State Park and portions of Bald Eagle State Forest in the eastern reaches of Centre County.

In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps was enlisted to rehabilitate clearcut areas in the county by planting millions of trees. The CCC effort encompassed most of the present lands of Black Moshannon State Park and nearby areas of Moshannon State Forest. These areas feature extensive plantations of red pine trees, which were preferred at the time for various financial and logistical reasons. Some of these plantations measure dozens of acres and are recognizable for evergreens that are now very tall but were clearly planted in rows.

Pennsylvania’s forests, though they now feature altered ecosystems, partially recovered after the clearcutting ended, and now approximately half of the Commonwealth features second and third-growth forests. However, many of these forests remain available to logging interests, and about one-fifth of the Commonwealth’s current forest lands are privately owned.

Private landowners in Centre County are permitted to sell timber to logging companies, but must observe Commonwealth requirements for routing haul roads, minimizing erosion and fire hazards, and preventing damage to streams and wetlands. Many of the county’s remaining forests are protected in the form of State Forests, and occasionally as State Game Lands, but the Commonwealth sells timber from these protected lands to logging firms as well.

Clearcutting is no longer permitted in Pennsylvania, and loggers are required to leave a percentage of an area’s trees standing to prevent complete destruction of the local ecosystem.

Ben Cramer

Sources:

Elder, Dustin, “Green Gold: ‘The Prince of Loggers,’ Bellefonte’s John Ardell Jr., Was a Keystone of Pennsylvania’s Timber Market.” Town & Gown, June 3, 2021.

Defebaugh, James Elliott, History of the Lumber Industry of America, vol. 2, second edition. Chicago, IL: The American Lumberman, 1907.

Fergus, Charles, Natural Pennsylvania: Exploring the State Forest Natural Areas. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002.

Hoover, Stephanie, Pennsylvania’s Historical Industries: Lumber, https://pennsylvaniaresearch.com/pennsylvania-lumber-industry.html (Accessed December 31, 2022).

Richard D. Schein and E. Willard Miller, “Forest Resources”, in A Geography of Pennsylvania, ed. E. Willard Miller (pg. 74-83). University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995.

Kline, Benjamin F. G. “Pitch Pine and Prop Timber.” The Logging Railroads of South-Central Pennsylvania. Book No. 1 in the Series Logging Railroad Era of Lumbering in Pennsylvania. Williamsport, PA: Lycoming Printing Co., 1971.

Kline, Benjamin F. G. “Wild Catting” on the Mountain: The William Whitmer & Sons Company Operations in Cambria, Centre, Clearfield and Union Counties, Pennsylvania and Cornwall, Rockbridge County, Virginia. Book No. 2 in the Series Logging Railroad Era of Lumbering in Pennsylvania. Williamsport, PA.: Lycoming Printing Co., 1970.

Thwaites, Tom, 50 Hikes in Central Pennsylvania, fourth edition, Woodstock, VT: Backcountry Books, 2001.

Centre County, Pennsylvania, Timber Harvesting, https://centrecountypa.gov/783/Timber-Harvesting (Accessed December 31, 2022).

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Waterways Engineering and Wetlands, Timber Harvest Operations Field Guide for Waterways, Wetlands and Erosion Control, 3150-BK-DEP4016 Rev. 1/2014, 2014.

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Timber Sales, https://www.dcnr.pa.gov/Business/TimberSales/Pages/default.aspx (Accessed December 31, 2022).

First Published: January 28, 2023

Last Modified: February 21, 2025