The Pennsylvania Match Company, founded in Bellefonte in 1899, quickly grew to become one of the largest match producers in the United States and employed up to 400 people before a reduced consumer demand for matches led to its closing in 1947.

Known locally as the “Match Factory,” the company’s sprawling brick complex between Spring Creek and Logan Branch in Bellefonte is now owned by the American Philatelic Society.

The company was established by Fountain W. Crider, Philip B. Crider, W. Fred Reynolds, and Joseph L. Montgomery. The factory was designed by a local architect, Robert Cole, and constructed from 300,000 bricks pressed nearby in Mill Hall. Samuel A. Donachy was hired away from match factories in Hanover and York, Pennsylvania, to be superintendent.

In 1900, the plant employed 75 workers. Matches were made from locally sourced white pine lumber until 1914, when, after a fire, it became necessary to order supplies by rail from out of state.

By 1911, the Pennsylvania Match Company was one of the eight largest match operations in the United States, with trademarked brands that included “Sunlight,” “Phoenix,” “Automobile, Competitor,” “Sterling,” “Keystone,” and “Quaker.” By 1912, the plant had become fully automated with the nearby Big Spring supplying water for its steam boiler.

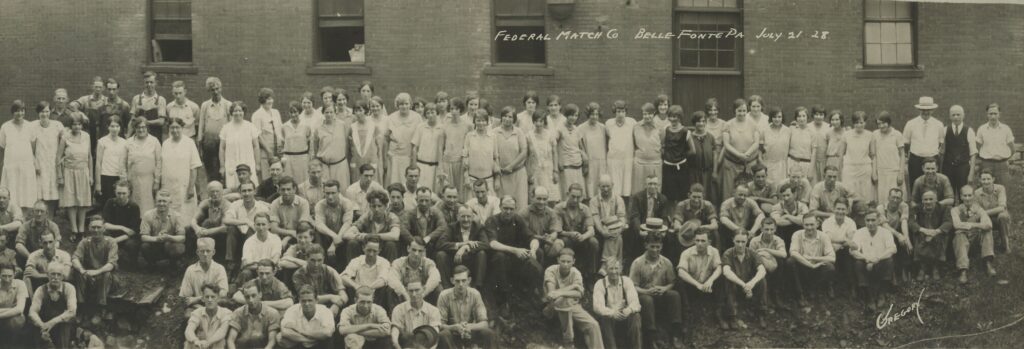

In 1923, the company was purchased by the Federal Match Corporation. That name is still visible on the factory’s gables facing Talleyrand Park.

Employment peaked at 400 during World War II, when the factory produced waterproof matches used by the military. Single-dip, strike-anywhere matches were in high demand, but the phosphorus white match heads were dangerous to produce because of the chemical used. The hazards of these strike-anywhere or “parlor matches” were so well known by 1911, that the U.S. Congress and President William Howard Taft intervened to have the safer match patent released for “humanitarian reasons.”

However, it was not until the 1930s, when Swedish technology was adopted under the expertise of E. Ivan Bjalme, that safety matches could be produced in Bellefonte. By this time, some workers had been exposed to chemicals and suffered from necrosis, known as “match poisoning” or “phosphorus jaw.”

Verna Houser was an employee in the company office during the 1930s and witnessed the effects of match poisoning on another employee who was a “match-tester.” Houser said the woman “got to have trouble with her teeth.” Her teeth were removed as were bones in her face later. “They said it was match poisoning,” Houser said. Factory workers voted to join the Match Workers Union in 1936.

In 1942, the company merged with the Universal Match Corporation. However, the factory closed in 1947 because consumers increasingly preferred lighters and book matches to wood matches, and more kitchens had electric ranges that did not have to be lighted.

The property was later purchased by M. L. Clasters & Sons, a building supply company, which converted it to offices and storage. After Clasters was sold in 1996, the buildings stood vacant for several years.

In 2001, the Match Factory was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The next year, the complex was purchased by the American Philatelic Society, which renovated the buildings to serve as its headquarters and as space for lease to others.

Matt Maris

Sources:

“A Large Factory for Bellefonte,” Democratic Watchman, September 29, 1899.

Manchester, Hugh. “The Big Spring.” Centre Daily Times, August 27, 1996.

National Register of Historic Places, Pennsylvania Match Company, Nomination Form.

First Published: August 15, 2021

Last Modified: March 3, 2025