Penn State fielded its first organized football team in 1887 — just 11 years after the rules of the sport were established — and has had a team ever since. Penn State’s football program has been among the most successful in the country, earning 902 victories through 2020 and winning national championships in 1982 and 1986. Penn State also endured, and ultimately survived, a major scandal in 2011 with the prosecution and conviction of its former defensive coordinator, Jerry Sandusky, for serial child sex abuse.

When the Nittany Lions defeated Rutgers 23-7 in 2020, they became the eighth team in the country to win 900 games. Along the way, they enjoyed 13 undefeated seasons. The program has produced more than 100 first-team All-Americans and a Heisman Trophy winner (John Cappelletti in 1973). Penn State holds the record for consecutive seasons without a losing record (49) and has been the dominant team in the East, winning the Lambert Trophy — given annually to the best team in the region — 31 times.

The university’s fame grew with the success of the Nittany Lion teams coached by Joe Paterno during his long tenure. But the Sandusky case brought anguish to the community and an abrupt end to Paterno’s tenure. Under Paterno’s coaching successors, Bill O’Brien and James Franklin, the Nittany Lions have again achieved success on the field as well as popularity among fans.

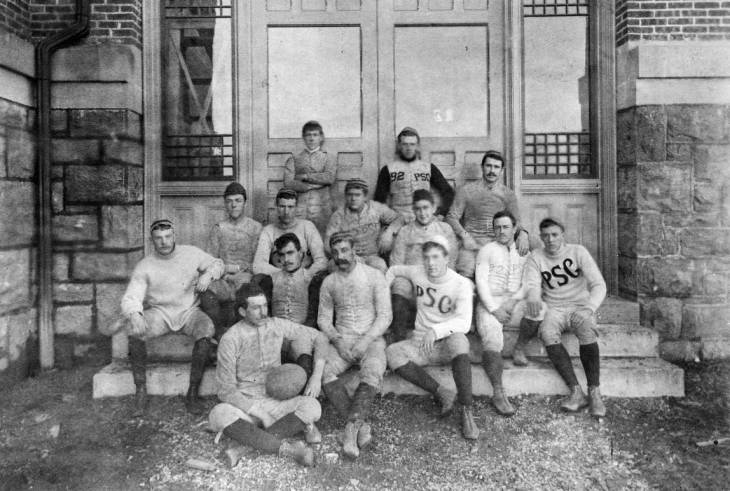

The first team captain at Penn State was George Linsz, a freshman who arrived at school with his own football and who, with fellow freshman Charles Heldebrand, organized a team that President George W. Atherton gave permission to represent the college. Known then as the Nittanymen, Penn State played its first game on November 5, 1887, defeating nearby Bucknell 54-0 at Lewisburg.

Football at the time was rough and primitive — the forward pass would not appear until 1906 — and injuries were common. In 1889, multiple Penn State players were banged up in a loss to Lafayette, but the team had a game two days later against powerful Lehigh. The result was a 106-0 rout that still stands as Penn State’s worst loss.

Nonetheless, within a few years, there were signs that football was catching on in State College. Beaver Field was built with a 500-seat grandstand and the first coach, George Hoskins, was hired. By 1912, Penn State produced its first full, perfect season at 8-0 under coach Bill Hollenback.

From very early in its history, college football was beset by controversy over who should be allowed to play and whether they should receive scholarships and other benefits. By the 1920s, reform-minded leaders were in ascendence in State College and, in 1927, the university’s Board of Athletic Control ended financial aid to the incoming freshmen of 1928. The board also banned scouting opponents. While those administrative moves may have kept Penn State closer to an amateur spirit, they also made it more difficult to recruit football players against schools that did offer scholarships.

The Nittany Lions suffered six losing seasons from 1928 to 1938. Fans were alarmed and, eventually, well-heeled alumni began to offer summer jobs to incoming players, making State College a more enticing destination. The Nittany Lions then went on their record-setting run of 49 seasons at .500 or above (1939-87). Tuition scholarships were reinstated in 1949.

The Alston brothers, Dave and Harry, of Midland, Pa., were the first Black players at Penn State, joining the team in 1941. Dave Alston stood out for the school’s unbeaten freshman team, but he died after a tonsillectomy operation the following August, though his death was blamed on injuries sustained in a spring scrimmage with Navy. Harry did not return to Penn State.

Wallace “Wally” Triplett became the first Black player to start in a varsity game for Penn State, when he played in a 33-0 loss to Michigan State in 1945. Despite the result, Triplett starred for the next several years and went on to become the first Black drafted by an NFL team (the Detroit Lions) to play in that professional league. In 1946, Penn State canceled its season finale at Miami (Fla.) when school officials in the then-segregated state asked Penn State to leave its two Black players, Triplett and Dennie Hoggard, at home.

A year later, Triplett and Hoggard were part of a fearsome Penn State team under longtime coach Bob Higgins that finished the regular season 9-0, won the school’s first Lambert Trophy, and ranked No. 4 in the AP poll — Penn State’s first top 10 finish. The team tied SMU in the 1948 Cotton Bowl, 13-13. Because Texas was segregated, the team had to stay at a Navy base outside Dallas.

Charles A. “Rip” Engle, the head coach at Brown, was named the new Penn State coach in April 1950, less than a month after the school’s Athletic Board set aside 30 scholarships exclusively for football. In an unusual arrangement, Penn State required Engle to keep the previous coaching staff on board, including his predecessor, Joe Bedenk. But he was allowed to bring one assistant from Brown. His choice was Brown’s quarterback from 1946 to 1949, Joseph Vincent Paterno.

Engle led the Nittany Lions from 1950 through 1965, an era in which the sport gained new fans thanks to televised games. With stars such as Lenny Moore and Dave Robinson, both later elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Engle compiled a record of 104-48-4 and won three bowl games.

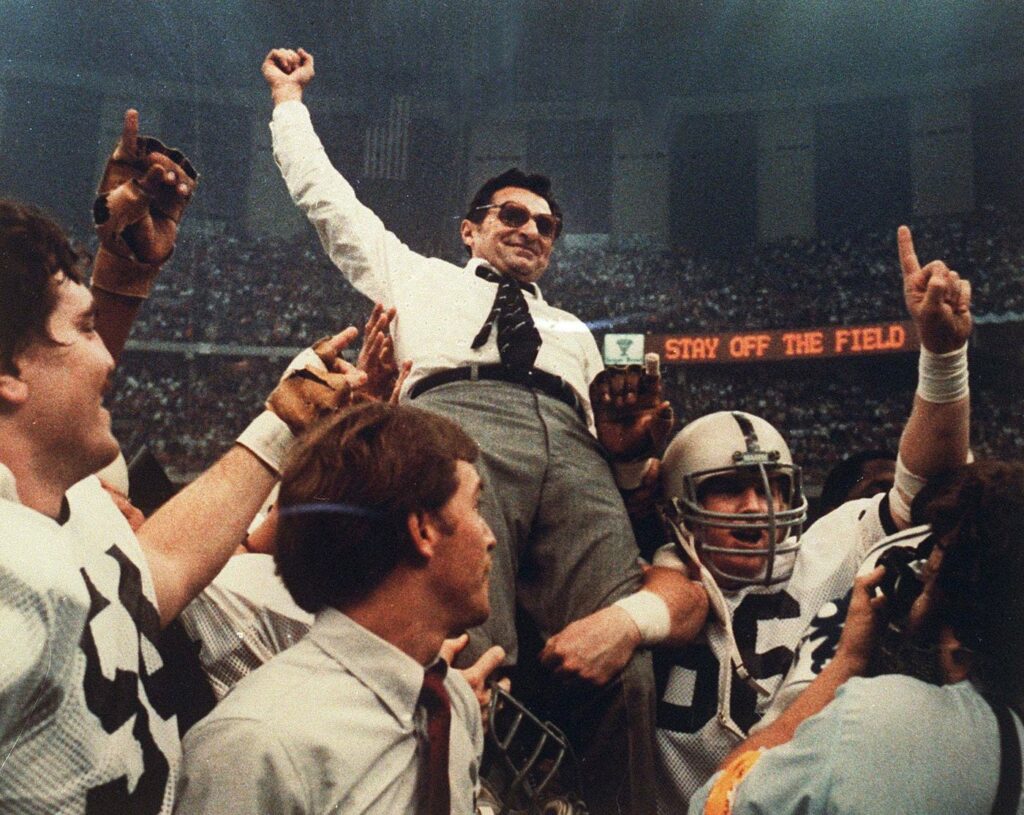

Paterno was designated as the successor to Engle in 1964 and took over as head coach in February 1966, beginning a 46-year tenure. Put simply, Paterno took a consistently good team and made it consistently great.

After a disappointing 5-5 season in 1966, Paterno spent most of the offseason reworking Penn State’s defense to be more aggressive, both in scheme and attitude. “Run to the ball!” would be a command that players heard scores of times over the course of a season. With stars on defense, offense and special teams suddenly drawn to State College, Penn State produced perfect seasons in 1968, 1969 and 1973, and lost just one game in 1971, 1977 and 1978.

Nonetheless, in an era in which national championships were decided by polling, the perceived weakness of Eastern football left Penn State on the outside. The Nittany Lions ended up second in the AP and UPI polls in 1968 and 1969, and fifth in 1973. Ideally, in those days, the Nos. 1 and 2 teams might be matched in a bowl game. Penn State got a chance at such a matchup in the Sugar Bowl at the end of the 1978 season, but fell to Alabama 14-7 after a goal line stand by the Crimson Tide late in the game.

Penn State and Paterno finally got their long-sought-after title on New Year’s Day 1983, when — again in the Sugar Bowl, this time against No. 1 Georgia — the Nittany Lions came out on top 27-23, clinched by a fourth-quarter 47-yard touchdown pass from Todd Blackledge to Gregg Garrity.

Penn State was No. 1 again at the end of the 1986 season, upsetting the swaggering Miami Hurricanes 14-10 in a Fiesta Bowl that saw the Nittany Lions intercept the Heisman Trophy winner, Vinny Testaverde, five times. All-American Shane Conlan returned one interception to the Miami 5-yard line to set up the winning score, and Pete Giftopoulos preserved the win with another interception at the Penn State goal line.

During this run of success in a sport plagued with a history of corruption, Penn State gained a reputation for winning with hard work, clean play, and attention to the academic side of its athletes’ experiences. Paterno turned down a more lucrative job coaching the New England Patriots in 1973, his third NFL offer, cementing himself as a hero at Penn State. He called his approach to college football a “Grand Experiment” to see if excellence in sports and academics could coexist, and Penn State adopted the slogan “Success With Honor.”

Penn State continued to be a football power in Paterno’s final decades as coach, though it never quite matched the consistent success of the late 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. After nearly a half century, the football team finally had a losing season in 1988 when it fell to Notre Dame, 21-3, in the season’s final game.

The Nittany Lions also benefited from an expanding fan base. Since 1960, when the team began playing in its current location, Beaver Stadium has been expanded three times to its current 106,572-seat capacity. It is the second-largest stadium in the United States.

After extensive private negotiations, Penn State joined the Big Ten Conference in the 1993. The move reflected the changing nature of college football in the cable television era, as even long-established independent teams such as Miami, along with traditional Penn State rivals Syracuse and Pittsburgh, moved into conferences to reap the financial benefits of broadcast deals.

The Nittany Lions made their presence felt in the Big Ten in 1994, going undefeated and beating Oregon in Rose Bowl. Once again, a perfect Penn State season was only good enough for No. 2 in the eyes of the pollsters: they voted Nebraska as No. 1.

It would be more than a decade before Penn State would win another Big Ten title — the school has won four in all — and that drought would include four seasons in five years (2000. 2001, 2003 and 2004) when Penn State was under .500.

Many Penn State fans and administrators began to argue that Paterno, now in his 70s, had coached long enough and should retire. But the matter was settled with an 11-1 season in 2005 that delivered a Big Ten championship and ended with an Orange Bowl win in overtime against Florida State, making Penn State No. 3 in the final AP poll.

On October 29, 2011, Penn State beat Illinois 10-7 to run its record to 8-1. It was Paterno’s 409th victory and the last game he would ever coach. On November 5, 2011, a Pennsylvania grand jury concluded a long investigation by charging Jerry Sandusky, the team’s defensive coordinator from 1977 to 1999, with sexually assaulting multiple boys over a period of years. He was convicted the following year on 45 out of 48 counts of sex abuse and was sentenced to 30 to 60 years in prison.

The sexual abuse scandal would have drawn attention anywhere, but with the squeaky-clean reputation of Penn State and Paterno, it quickly became a top national news story. Paterno expressed regret he did not do more and offered to resign at the end of the season but, on the night of November 9, 2011, the Board of Trustees fired him. Days later, Paterno was diagnosed with lung cancer, and he died on January 22, 2012.

Paterno’s firing did not end the trouble for Penn State created by Sandusky’s crimes. In July 2012, an independent commission hired by the university to investigate the scandal blamed administrators, including Paterno, for allowing Sandusky to prey on young people. While Paterno supporters vigorously disputed that conclusion, the NCAA — the college sports governing body — bypassed its own investigative process and issued a series of sanctions. Penn State was fined $60 million and banned from bowl games for four years. Scholarships were reduced by as many as 20 a season, and players would be allowed to transfer without having to sit out a year, which was the rule at the time.

With rivals looking to lure Penn State stars away from State College, a new head coach and key Nittany Lion players rallied to hold the team together. The coach, Bill O’Brien, a former New England Patriots assistant, was aided immeasurably by the examples set by players such as Michael Mauti and Michael Zordich. Only nine players eventually transferred. The 2012 Nittany Lions responded with an 8-4 season, and then put together a 7-5 record in 2013, upending Wisconsin in the season finale both years. O’Brien left Penn State after his second season to become head coach for the NFL’s Houston Texans.

He was replaced in 2014 by the current head coach, James Franklin, who had made Vanderbilt a winner in the Southeastern Conference. The first Black head football coach at Penn State, Franklin has brought the Nittany Lions back to national prominence with a Big Ten title in 2016, two major bowl victories, and three top-10 finishes in the national rankings.

Penn State benefited from the early lifting of the NCAA sanctions in September 2014. NCAA president Mark Emmert had been widely criticized for overstepping his authority in levying the sanctions and punishing players who had nothing to do with the Sandusky case. Additionally, in January 2015, the NCAA restored the 112 Penn State wins that had been vacated as a result of the scandal, which meant that Paterno’s 409 victories once again were the record for a Division I coach.

Penn State continues to compete in the Big Ten’s East division, facing nine conference opponents each season.

John Affleck

Sources:

Chambers, Randy. “Penn State Sanctions: Timeline of Sandusky Scandal That Brought NCAA Penalties.” July 23, 2012. Bleacher Report, July 23, 2012.

Eder, Steve and Mac Treacy. “NCAA Decides to Roll Back Sanctions Against Penn State.” The New York Times, September 8, 2014.

Posnanski, Joe. Paterno. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Prato, Lou. The Penn State Football Encyclopedia. Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing, 1998.

Rapport, Ken and Barry Wilner. Penn State Football: The Complete Illustrated History. New York: MVP Books, 2009.

Revsine, Dave. The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation. New York: Lyons Press: 2014.

Stuetz, John. “Surviving the Sanctions: Inside the Tumultuous Journey of Penn State’s Seniors.” Bleacher Report, May 8, 2015.

Penn State Football: 2020 Media Guide, Penn State Athletics. 2020.

First Published: August 16, 2021

Last Modified: February 11, 2023